Like nuclear power plants and sensitive computer networks, the safest rare book collections are protected by what is known as “defense in depth”—a series of small, overlapping measures designed to thwart a thief who might be able to overcome a single deterrent. The Oliver Room, home to the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s rare books and archives, was something close to the platonic ideal of this concept. Greg Priore, manager of the room starting in 1992, designed it that way.

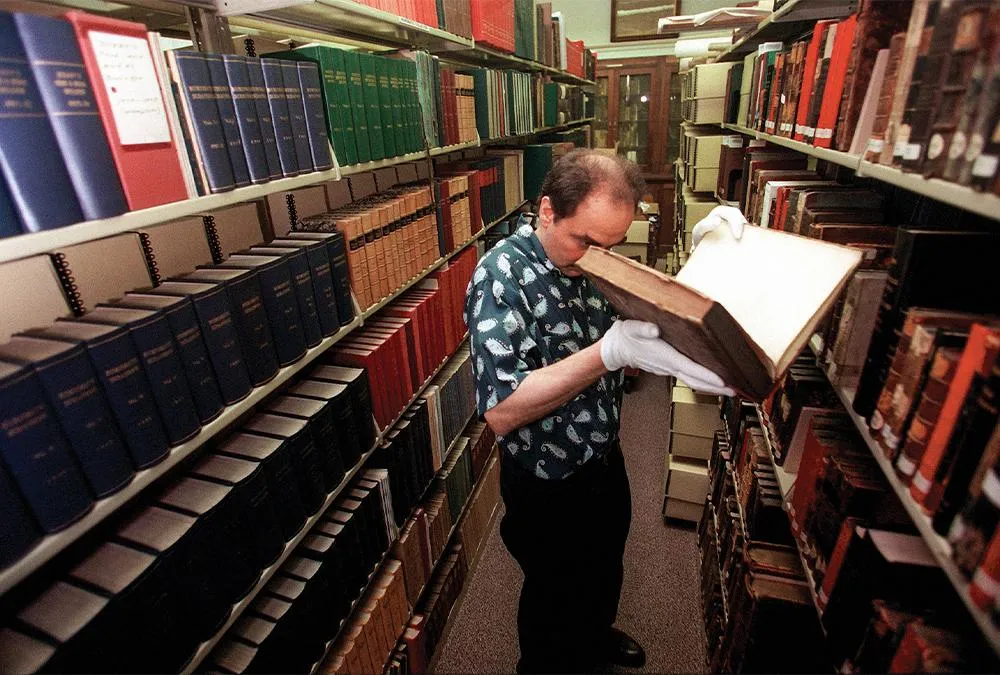

The room has a single point of entry, and only a few people had keys to it. When anyone, employee or patron, entered the collection, Priore wanted to know. The room had limited daytime hours, and all guests were required to sign in and leave personal items, like jackets and bags, in a locker outside. Activity in the room was under constant camera surveillance.

In addition, the Oliver Room had Priore himself. His desk sat at a spot that commanded the room and the table where patrons worked. When a patron returned a book, he checked that it was still intact. Security for special collections simply does not get much better than that of the Oliver Room.

In the spring of 2017, then, the library’s administration was surprised to find out that many of the room’s holdings were gone. It wasn’t just that a few items were missing. It was the most extensive theft from an American library in at least a century, the value of the stolen objects estimated to be $8 million.

* * *

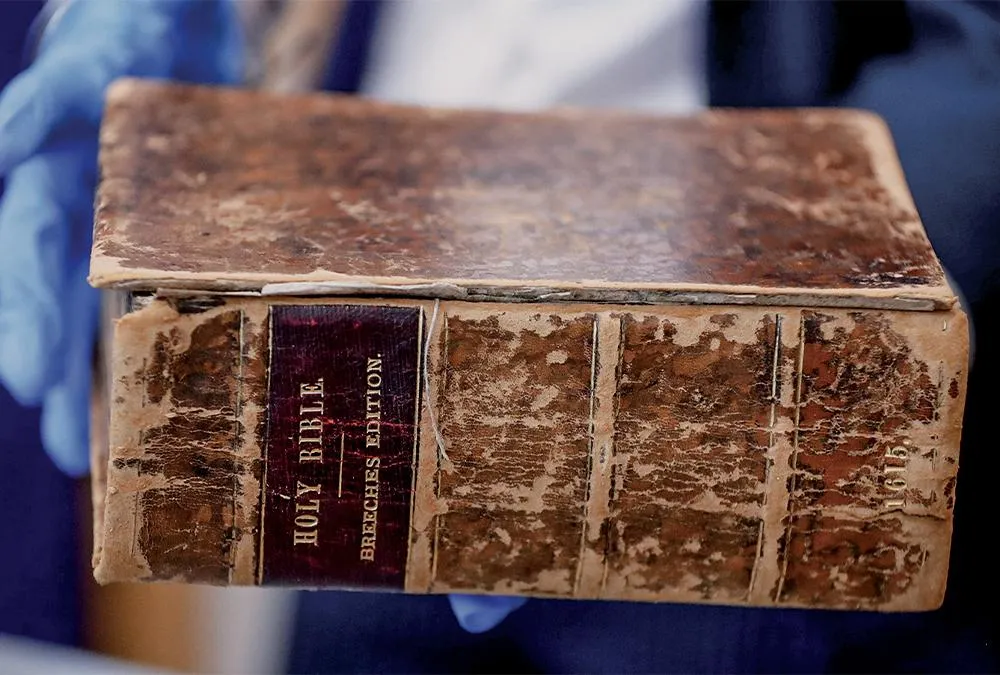

There are two types of people who frequent special collections that are open to the public: scholars who want to study something in particular, and others who just want to see something interesting. Both groups are often drawn to incunables. Books printed at the dawn of European movable type, between 1450 and 1500, incunables are old, rare and historically important. In short, an incunable is so valued and usually such a prominent holding that any thief who wanted to avoid detection would not steal one. The Oliver Room thief stole ten.

Visitors and researchers alike love old maps, and few are more impressive than those in Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, commonly known as the Blaeu Atlas. The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s version, printed in 1644, originally comprised three volumes containing 276 hand-colored lithographs that mapped the known world in the age of European exploration. All 276 maps were missing.

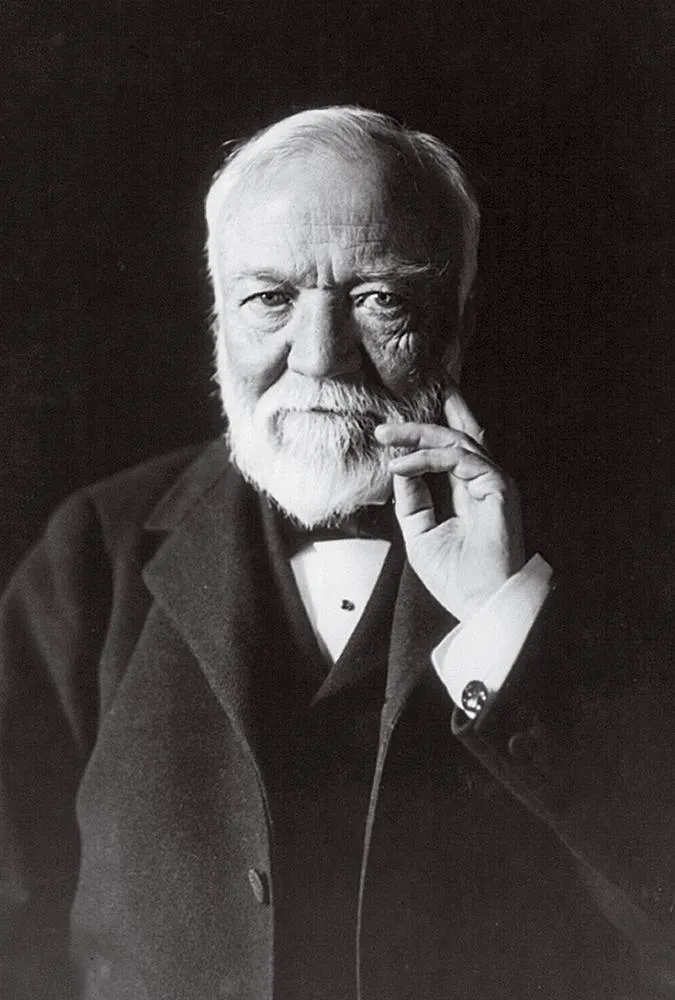

Many of the library’s holdings had been donated over the years by the founder, Andrew Carnegie, and his friends. But in one notable instance, the library allotted money specifically to purchase 40 volumes of photogravure prints of Native Americans created by Edward Curtis in the first decades of the 20th century. The images were beautiful, historically valuable and extremely rare. Only 272 sets were created; in 2012, Christie’s sold one set for $2.8 million. The Carnegie Library’s set held some 1,500 photogravure “plates”—illustrations made apart from a book and inserted into it. They had all been cut and removed from their bindings, “except a few scattered throughout of unremarkable subjects,” a book expert later noted.

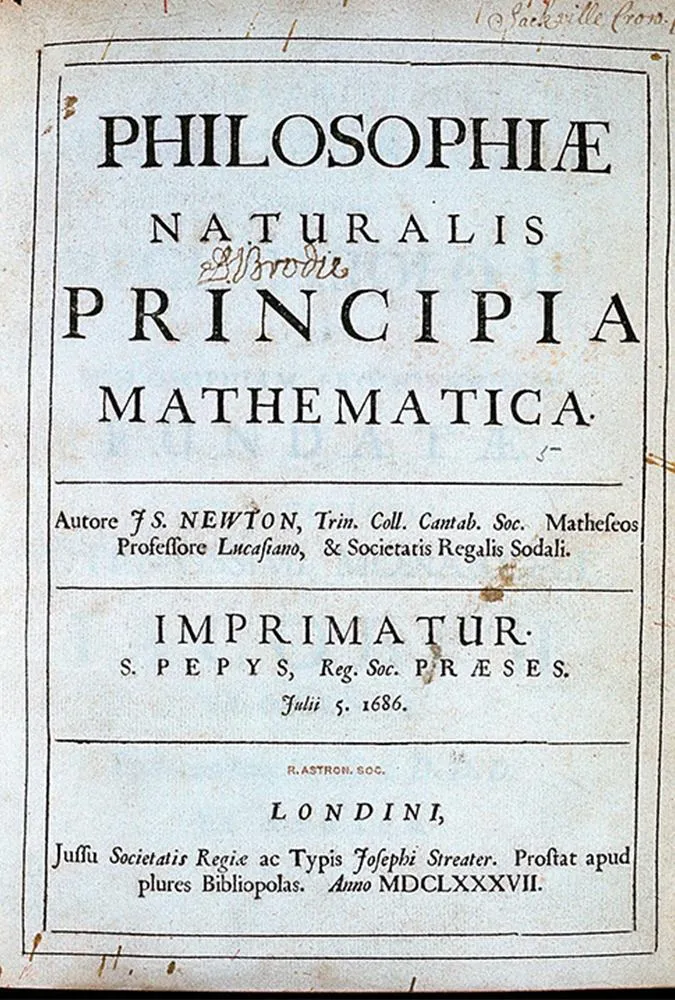

And this was just the beginning. The person who worked over the Oliver Room stole nearly everything of significant monetary value, sparing no country or century or subject. He took the oldest book in the collection, a collection of sermons printed in 1473, and also the most recognizable book, a first edition of Isaac Newton’s 98. He stole a first edition of The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, a letter written by William Jennings Bryan and a rare copy of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s 1898 memoir, Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences 1815-1897. He stole a first edition of a book written by the nation’s second president, John Adams, as well as a book signed by the third, Thomas Jefferson. He stole the first English edition of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, printed in London in 1620, and the first edition of George Eliot’s Silas Marner, printed in the same city 241 years later. From John James Audubon’s 1851-54 Quadrupeds of North America, he stole 108 of the 155 hand-colored lithographs.

In short, he took nearly everything he could get his hands on. And he did it with impunity for close to 25 years.

* * *

When a library finds that it has been the victim of a major theft, it can take a long time to determine what is missing; an inspection of each shelved item and its pages is a laborious process. But the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s rare and antiquarian collection had already been well documented, ever since the administration moved to establish an archive of the institution’s rarest holdings. Greg Priore, who had graduated with an M.A. in European history a few years earlier from nearby Duquesne University, was then working in the library’s Pennsylvania Room, a space dedicated to local history and genealogy. He was also pursuing a library science degree at the University of Pittsburgh, with an emphasis on archives management. Both on paper and in person, he seemed like the perfect candidate to run the new archive, and was hired in 1991 to oversee what became the Oliver Room collection in 1992.

Priore comes across as professional but easygoing, the sort of guy who knows a lot but wears his knowledge lightly. Just under six feet tall, with a resonant voice and a prominent mustache, he was the son of a local obstetrician and spent the bulk of his life within walking distance of the Carnegie Library. An important job at a prestigious institution in his home city was something like a dream.

After getting the job, he worked alongside a preservation specialist to assess the Carnegie Library’s rare and antiquarian books. In addition, two rare book experts hired to offer conservation advice found that the library had given little thought to preserving its oldest books. So the staff blocked off windows to get control of the climate, substituted metal shelves for the old ones made of wood, which can leach acid into books, and upgraded the security system. In 1992, the room was officially renamed for William R. Oliver, a longtime benefactor. For years it served as the jewel of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Docents took patrons on tours, and C-SPAN said it was one of western Pennsylvania’s cultural high points. Scholars and journalists plumbed its archives.

In the fall of 2016, library officials decided it was time to audit the collection again, and hired the Pall Mall Art Advisors to do the appraisal. Kerry-Lee Jeffrey and Christiana Scavuzzo began their audit on April 3, 2017, a Monday, using the 1991 inventory as a guide. Within an hour, there was trouble. Jeffrey was looking for Thomas McKenney and James Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America. This landmark work included 120 hand-colored lithographs, the result of a project that began in 1821 with McKenney’s attempt to document in full color the dress and spiritual practices of Native Americans who had visited Washington, D.C. to arrange treaties with the government. The three-volume set of folios, produced between 1836 and 1844, is large and gorgeous and would be a highlight in any collection. But the Carnegie Library’s version had been hidden on a top shelf at the end of a row. When Jeffrey discovered why, her stomach dropped. “Once a plump book filled with plates,” she would recall, “the sides had caved in on themselves.” All those stunning illustrations had been cut from the binding.

The appraisers discovered that many of the invaluable books with illustrations or maps had been ransacked. John Ogilby’s America—one of the greatest illustrated English works about the New World, printed in London in 1671—had contained 51 plates and maps. They were gone. A copy of Ptolemy’s groundbreaking La Geographia, printed in 1548, had survived intact for over 400 years, but now all of its maps were missing. Of an 18-volume set of Giovanni Piranesi’s extremely rare etchings, printed between 1748 and 1807, the assessors noted dryly, “The only part of this asset located during on-site inspection was its bindings. The contents have evidently been removed from the bindings and the appraiser is taking the extraordinary assumption that they have been removed from the premises.” The replacement value for the Piranesis alone was $600,000.

Everywhere they looked, the auditors found a staggering degree of destruction and looting. They showed their results to the head of the Preservation Department, Jacalyn Mignogna. She, too, felt sick. After seeing historic volume after historic volume reduced to stubs, she went back to her office and wept. On April 7, only five days after the appraisers had begun their inquiry, Jeffrey and Scavuzzo met with the library’s director, Mary Frances Cooper, and two other administrators, and detailed what they had already found—or, rather, not found. The next phase of their analysis would have a more pessimistic focus: Now they would try to determine just how far the collection’s value had fallen. On April 11, a Tuesday, Cooper had the lock to the Oliver Room changed. Greg Priore was not given a key.

* * *

Just about the only thing that keeps an insider from stealing from special collections is conscience. Security measures may thwart outside thieves, but if someone wants to steal from the collection he stewards, there is little to stop him. Getting books and maps and lithographs out the door is not much harder than simply taking them from the shelves.

While other cultural heritage thieves have gone to great lengths to avoid calling attention to their acts—stealing items of low value, destroying card catalog entries, ripping out bookplates, bleaching library stamps from pages—Priore took the best stuff he could find, and brazenly left the library stamps in, as the library would see when it began to regather the books. Despite this cavalier approach, he was astonishingly successful, more successful than any insider book thief in memory.

Priore and his wife, who worked as a children’s librarian, hardly had an opulent lifestyle; the couple lived in a modest apartment crowded with books. But they had four children, who attended private schools: St. Edmund’s Academy, the Ellis School and Duquesne University.

All indications suggest that he was perpetrating his crimes not to get rich but rather, as he told police, merely to stay “afloat.” For example, in the fall of 2015, Priore wrote an email to the Ellis School asking for an extension on tuition payments. “I am trying to juggle tuition payments for 4 kids,” he wrote. A few weeks later, he asked Duquesne officials to lift a hold on accounts assigned to two of his children, since he had made overdue tuition payments. In February 2016, Priore asked his landlord for an extension, falsely claiming his wife had missed work because of a heart attack. The rent was four months past due.

* * *

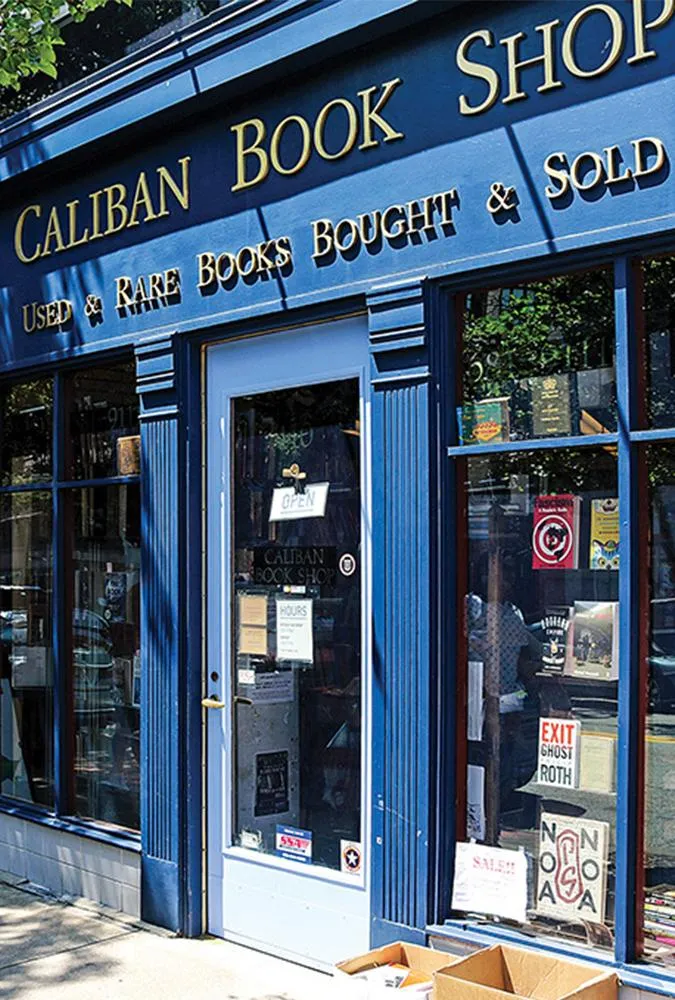

Priore lived close enough to the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh that he could walk to work in 15 minutes. One route took him past the famous blue edifice of the Caliban Book Shop, one of the city’s best-known cultural spots. The store was founded in 1991 by a Pittsburgher named John Schulman, who is 5 feet 7 inches tall and stocky, with close-trimmed, thinning gray hair and, often, a graying goatee blending into a few days’ growth of beard.

Schulman started his bookselling business in the 1980s, working out of a Pittsburgh apartment. Gregarious and diligent, he acquired the sort of status that comes from years of reputable work in the profession. He was a member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America (ABAA), serving on its board of governors for the Mid-Atlantic chapter. He was also an appraiser for regional institutions, including the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University and Penn State. After decades selling rare books, he was familiar to most in the business and even somewhat well known outside of it: Thanks to appearances on “Antiques Roadshow,” he was PBS-famous.

For the most part, Schulman treated the books, maps or prints that Priore brought him exactly as he would process the rare and antiquarian materials he got from any source. He would describe an individual book in ways people in the market would understand and, depending on the quality of an item, list it on his website. But with the items Priore brought, there was an added step.

When a book of value or importance is acquired by a library, the institution marks it using one of several different kinds of stamp: ink, emboss or perforation. These marks, which state the name of the library, are meant to do two things: identify the rightful owner and destroy the value of the book for resale. Most major special collections, like the Oliver Room, also adhere a bookplate to the inside front cover.

To sell such a heavily marked book, a typical thief would have to tear, cut and bleach away this evidence; if he was not careful, he would destroy in the process much of what made the book valuable in the first place. Schulman found another way to ready a stolen book for sale. Using materials he kept at his store, whenever he got a Carnegie book from Priore, he or one of his employees pressed a small red stamp, bright as lipstick, on the bottom of the bookplate. It pronounced the book “Withdrawn from Library.” That mark was to counteract the others.

While there is a tradition of librarians and archivists stealing from collections they are meant to steward, not since the 1930s had a dealer as highly reputed as Schulman been implicated. In the 1970s and ’80s, a flamboyant Texas bookman and one-time president of the ABAA named John Jenkins made money selling stolen and forged items to libraries and collectors. But most of his malfeasance was confined to Texas—and no one who knew Jenkins would have been surprised to discover he was an outlaw. He was an indebted gambler who had burned his own store for insurance money, and his life ended in 1989 with a gunshot to the head (authorities differ over whether it was a homicide or a suicide).

Schulman, a constant presence at the major book fairs, seemed as rock-solid as any bookseller in the business—all of which made him the perfect fence for Priore. The librarian could not risk approaching dealers or collectors directly with the types of books he was selling, and the internet would have exposed him the first time he tried to sell an incunable. Priore simply could not have operated without Schulman’s help and good name—and Schulman could not have gained access to the Oliver Room’s big-ticket items without Priore.

* * *

Apparently Greg Priore knew he was about to get caught six months before it happened. In the fall of 2016, when the library administration was discussing the possibility of an appraisal of the Oliver Room—which would necessarily uncover missing assets—he argued against it. But his colleagues chalked it up to his general obstinacy against having others in his domain, an obstinacy that one librarian noted had grown increasingly pronounced as the years ticked by. Still, with or without Priore’s approval, the administration decided to go ahead with the assessment.

Priore talked to Schulman about it, and the bookseller tried to help his supplier by emailing a number of possible explanations for why many items were missing. Some items might be out for repair or loan, Schulman offered, urging Priore to create documents attesting to this. He also suggested saying the library’s former director, now dead, had talked about selling off some of the Oliver Room’s better books, and that he might have done so while Priore was away on leave. And Schulman proposed emphasizing “that the Oliver Room is fairly porous and accessible...[and] that there have no doubt been multiple opportunities for many different staff and visitors to enter the rooms without proper protocol.”

For his part, Priore suggested that the room’s defenses weren’t perfect. When library administrators interviewed him on April 18, 2017, he told Cooper, the director, that he did leave catalogers, interns and volunteers to work by themselves in the room. He added that maintenance workers—in particular, some men who had done repairs to the roof—had access to the room.

In the end, though, there was no way to hide his decades of crimes. Thousands of plates, maps and photographs were missing; clearly, this was not the work of a patron or workman who had enjoyed a few minutes’ unfettered access. Even if someone else had been stealing from the library, it would have been impossible for Priore not to notice so much was missing. In April he was suspended from his job and in June he was fired.

Pittsburgh police began a formal investigation in June, and on August 24 executed search warrants at Priore’s home, the Caliban Book Shop and a Caliban warehouse. Police questioned Priore the same day. It didn’t take long for him to come clean.

When police went to the Caliban warehouse, they brought along Christiana Scavuzzo of Pall Mall Art Advisors. She found, among other items, 91 of the Edward Curtis prints and seven maps from the Blaeu Atlas. Police also found the stamp that Schulman used to indicate that the books he sold had been deaccessioned from the library.

* * *

Bill Claspy is twice a graduate of Case Western Reserve University, with a B.A. and an M.A. in English literature, and today serves as head of special collections for the university’s main library. Despite his love for the humanities, he knows it is the sciences that keep the lights on at Case Western. That’s why he was especially sad to surrender an important book of scientific history.

In August 2018, he received an email from Lyle Graber, a detective in the Allegheny County District Attorney’s office in Pennsylvania, about a recently purchased book of early modern astronomy. “While reviewing evidence in this case,” Graber wrote, “it appears that in 2016 you purchased Quaestiones in Theoricas in Georgii Purbachii from...Caliban Books. Unfortunately, it is very possible that this book is among those having been stolen from the Carnegie Library and sold to unsuspecting buyers such as yourself.”

Schulman’s catalog description noted the book’s condition was “very good with minor ex-library marks.” Claspy retrieved the book from its shelf and saw what Schulman meant by “ex-library marks”: The first two pages had several stamps and an ash-blue rectangular bookplate from the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Below the bookplate was a small set of red letters pronouncing the book “Withdrawn from Library.” Claspy carefully wrapped the book and sent it back to Pennsylvania.

Around the same time, a private collector named Michael Kiesel also received an alarming letter. Kiesel had purchased one of the incunables that Priore had stolen and Schulman had sold to a reputable dealer in England. That dealer asked Kiesel to return the book to Detective Graber, which Kiesel did.

Dozens of people—private collectors, librarians and rare book dealers—received similar letters that August. They sent the books and documents to Allegheny County, where they have become part of a small but extremely valuable library under the supervision of the district attorney.

* * *

This past January in an Allegheny County court, Priore pleaded guilty to theft and receiving stolen property, while Schulman pleaded guilty to receiving stolen property, theft by deception and forgery. The guidelines for such crimes recommend a standard sentence of nine to 16 months’ incarceration but include two other possibilities: an aggravated range of up to 25 months’ incarceration, and a mitigated range that could include probation.

Much of what governs sentencing in property crimes comes down to the numbers. The Pall Mall Art Advisors spent months determining the replacement value for each item Priore had destroyed or stolen outright. The total, they concluded, was more than $8 million. But even this number, they said, was inadequate, since many items were irreplaceable—not available for purchase anywhere at any price.

Claspy argued that the value of rare books, maps and archival documents cannot be measured by money alone. “This crime was not just a crime against my library, or the Carnegie Library, it was a cultural heritage crime against us all,” he wrote to the judge. The director of the University of Pittsburgh Libraries, Kornelia Tancheva, wrote that a rare book theft, “especially from a public library, is an egregious crime against the integrity of the cultural record and against the public good.”

Further, the Pall Mall Art advisers wondered what books might have been donated to the library in the future, benefiting the people of Pittsburgh, if Greg Priore had not devastated the library’s reputation as well as its holdings. The chilling effect on donors is one reason that many libraries, upon discovering losses from their collections, keep the matter quiet.

More than two dozen people wrote letters asking the judge, Alexander Bicket, to impose strict sentences—not always a certainty in crimes involving thefts from a library. At an in-person sentencing on June 18, where Priore apologized for his thefts (“I am deeply sorry for what I have done,” he said), several spoke about the terrible effects of these crimes. “We do not want an apology,” Cooper told the judge. “Any apology from these thieves would be meaningless. They are only sorry that we discovered what they did.” Still, Judge Bicket was not swayed. He sentenced Greg Priore to three years’ house arrest and 12 years’ probation. Schulman received four years’ house arrest and 12 years’ probation. Both Schulman and Priore, through representatives, declined to speak to Smithsonian.

After the sentences were made public, Carole Kamin, a member of the board of the Carnegie Natural History Museum, wrote to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that supporters of local nonprofits “were appalled at the unbelievably light sentences.”

Numerous booksellers have told me that they believe in Schulman’s innocence, saying he was duped—a view the bookseller himself encouraged in an email to colleagues before the sentencing, in which he insisted he pleaded guilty only to save legal costs and put the matter behind him.

Others in the rare book world, though, say the evidence gathered by police was convincing. For instance, Schulman did engage in legitimate business with the Carnegie Library over the years, and on those occasions when he purchased a book through proper channels, he wrote checks payable to the library. But when he bought books from Priore, he made the checks payable to Priore—or paid cash.

It was Schulman’s responsibility, as one bookseller told me, to notice there was something odd about the treasures Priore was handing over. The ethics code of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America states that members “shall make all reasonable efforts to ascertain that materials offered to him or her are the property of the seller,” and members “shall make every effort to prevent the theft or distribution of stolen antiquarian books and related materials.” Schulman was not only a member of the ABAA. He had served on its ethics and standards committee.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/48/4848dbaf-5d7d-40a7-b446-1b2b553d819e/mobile_opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/fd/6afdb11f-a9ad-4ecc-8a1c-36d3e38f36d6/social_media_image.jpg)