Is There Such a Thing as a “Bad” Shakespeare Play?

More than four hundred years after the Bard’s death, the quality of his works is still a fluid scale

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/19/3319b7d4-15b3-475a-87a6-c36106d2cd56/11221026034_2875e25bf3_o.jpg)

King Lear used to be a bad play.

William Shakespeare’s tale of a king driven mad by his blind, selfish need to be conspicuously loved, King Lear, hit the stage in December 1606, performed for King James I and his court at Whitehall as part of the Christmas revels. There’s no way of knowing whether the play was a success at the time, but the fact that it was published in 1608 in a quarto edition – a small, cheap book for the popular press, like a proto-paperback – seems to suggest that it was liked.

By the second half of the century, however, Shakespeare’s plays were no longer fashionable and while audiences appreciated that there was a good story in Lear, they didn’t like it—it was too grim, too dark, too disturbing, and it uncomfortably attempted to mix comedy and tragedy. So they fixed it. In 1681, poet Nahum Tate, in his extensive rewrite of the play, took “a Heap of Jewels, unstrung and unpolisht” and, with the addition of a love story and happy ending, sought “to rectifie what was wanting in the Regularity and Probability of the Tale”. For more than 150 years, Tate’s more sentimental version became the Lear everyone knew, his Lear the one actors became famous playing; if you saw a production of Lear, it was Tate’s words, not Shakespeare’s, you heard. (Except between 1810 and 1820, when no one in England at least saw any version of Lear: Perhaps understandably, all performances of a play about a mad king were banned during the period of George III’s mental illness.)

In the 19th century, however, Shakespeare’s Lear was rediscovered by a new audience, one seemingly ready not only for the play’s darkness but also to embrace Shakespeare fully and without reservation. The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, writing in 1821, declared, “King Lear… may be judged to be the most perfect specimen of the dramatic art existing in the world,” and opinions only went up from there. Now, Shakespeare’s Lear is considered one of his best plays, if not the best. A survey of 36 eminent Shakespearean actors, directors, and scholars told The Times in March that it was their favorite, and a similar survey conducted by The Telegraph in 2008 placed it in the top three. The Telegraph noted in 2010 that it had been performed more times in the previous 50 years than it had ever been produced in the 350 years before that. The course of King Lear, like true love or Shakespeare’s own fortunes, never did run smooth.

That Lear, now the best of Shakespeare’s best, could have been so disliked highlights why it’s difficult to come up with a comprehensive ranking of the Bard’s plays. The question of whether a play is “good” or “bad” depends on who’s doing the asking, when and even where, and is further complicated by the Bard’s outsized reputation.

This April 23 marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death (as far as we can tell; history didn’t record the exact day). It’s also, by weird coincidence, the day we celebrate his birthday, so he would have been just 53 exactly the day he died. He’s buried in his hometown, Stratford-upon-Avon, and while he was likely mourned widely, it would have been nothing like the accolades heaped on his balding head now. Shakespeare, despite the efforts of notable dissenting critics and writers to forcibly eject him, has occupied the position of world’s greatest playwright since his star was re-affixed to the firmament in the late 18th century. No other playwright is as universally revered. No other playwright has had countless theses and courses and books and articles speculative novels and so many buckets and buckets of ink devoted to him. And while to works of other playwrights of the era are still performed today – Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson spring to mind – Shakespeare is far and away the most recognized.

Given that, it’s difficult to locate any of his plays that are wholly without defenders. Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, one of those notable dissenting critics, wondered if they doth protest too much: “But as it is recognized that Shakespeare the genius can not write anything bad, therefore learned people use all the powers of their minds to find extraordinary beauties in what is an obvious and crying failure,” he wrote in a widely distributed 1907 essay detailing his dislike for the playwright.

“We still have this picture of him as this universal genius and we’re uncomfortable with things that don’t fit that picture,” says Zöe Wilcox, curator of the British Library’s “Shakespeare in Ten Acts,” a major exhibition exploring the performances of Shakespeare’s plays that made his reputation. Shakespeare mania first gripped England in 1769, following the Shakespeare Jubilee put on by noted actor David Garrick in Stratford-upon-Avon.

“By the end of the 18th century, you get this almost hysteria where Shakespeare has been elevated to godlike proportions,” says Wilcox. “It’s sort of self-perpetuating: The more we talk about and revere Shakespeare, the more we have to have him live up to that.”

As the example of Lear illustrates, whether or not a play is considered good or bad is in part dictated by its cultural context. Shakespeare’s sad Lear didn’t work for audiences uninterested in seeing a king divested of his throne; after all, they’d just endured the Restoration, installing a king back on the throne after the tumultuous Cromwell years. That Lear is increasingly popular today, outstripping Hamlet for the top slot, is perhaps not surprising given our cultural context: The play portrays children dealing with an aging parent suffering from dementia, a topic now very much at the fore of our social conscious.

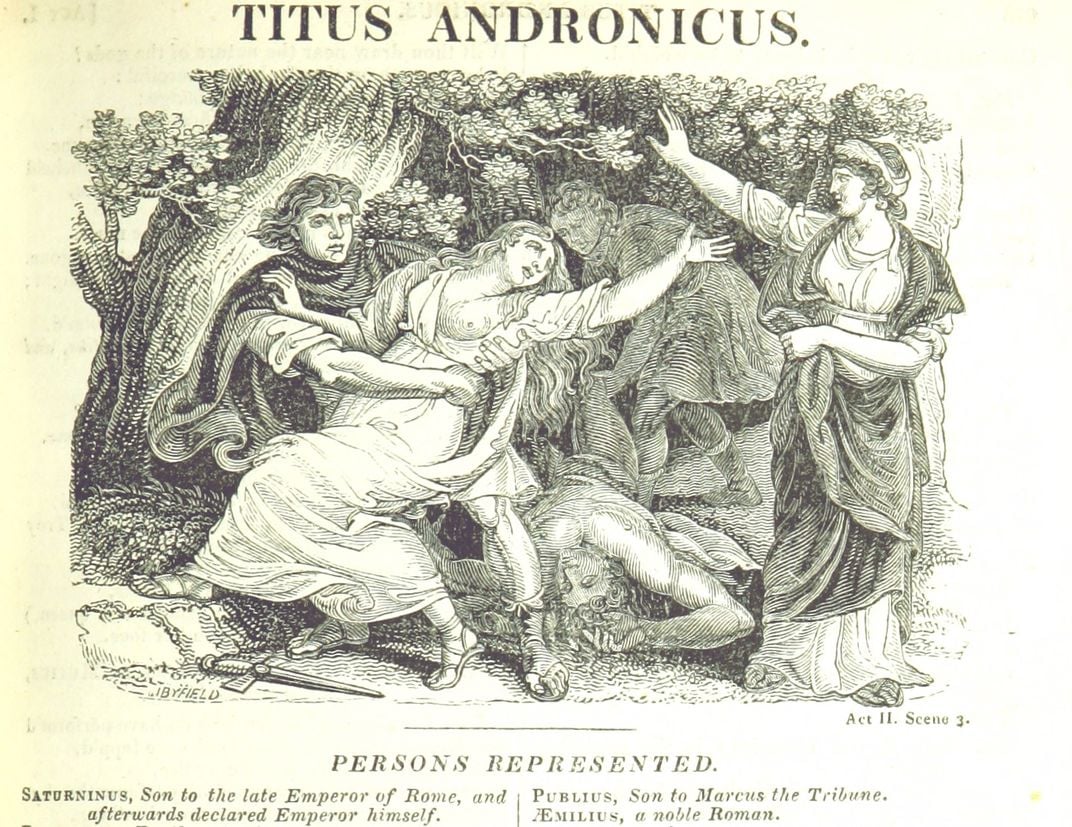

Where Lear was too sad to be borne, Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare’s bloody meditation on the cycle of violence set in martial Rome, was too violent. Like Lear, however, it’s another prime example of a reclaimed play. When it was first put on stage, sometime between 1588 and 1593, the play was a popular one-up on the first big revenge tragedy, The Spanish Tragedy, or Hieronimo Is Mad Againe, by Thomas Kyd. Where that play is gruesome – three hangings, some torture, a tongue bitten out – Titus is awash in blood and gore. In perhaps its most brutal scene, Titus’s daughter, Lavinia, sees her husband murdered by the two men who will, off stage, rape her, and cut off her hands and tongue to keep her from naming them. Later, Lavinia is able to scrawl their names in the dirt using a stick clamped in her jaws. Titus, by now having also seen two of his sons framed and beheaded for the murder of Lavinia’s husband, bakes the rapists into a pie and feeds them to their mother. Almost everyone dies.

“You can certainly understand why the Victorians and Georgians didn’t want to deal with this play,” says Ralph Alan Cohen, director and co-founder of the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton, Virginia, one of the country’s major centers for Shakespearean scholarship. Deal they didn’t; many notable critics even claimed that the play was so barbaric that genteel Shakespeare couldn’t possibly have written it, despite its inclusion in the 1623 First Folio. But Titus was brought back into the canon (albeit with the caveat that it may have been co-authored by George Peele) and onto the stage, in the middle of the 20th century, right around the time, Cohen says, that real-life violence became increasingly visible. “When we started watching on our TV the horrors that are out there… it became wrong not to admit that those things are out there,” he says. Though not as popular as the really big ones – Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Lear – Titus is being produced and adapted more often, including director Julie Taymor’s 1999 film version starring Anthony Hopkins and Jessica Lange. (Not that we’re entirely ever ready for it: Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London staged a production last year; every performance saw two to four people faint at the sight of all that blood. As The Independent gleefully pointed out, at 51 performances, that’s more than 100 people down.)

“The prevailing cultural context around it has dictated whether or not that play is popular in history. It’s having a resurgence now; in our “Game of Thrones” world, we’re quite into bloodthirsty history now,” says Wilcox, noting too that Titus would have appealed to Shakespeare’s contemporary audiences, who might have just come from bear-baiting and wouldn’t shy from a public execution. “We just live in such a horrible world at the moment, when you turn on the news and you see what’s happening in Syria and the terrorist happenings. We’re experiencing these things, if not directly, then through our TV screens, so it’s cathartic to see that in the theatres.”

Cohen would say that there aren’t really any plays we could put in the “bad” category anymore—plays that were once too sexy, too violent, too boring, too politically untouchable are now brought out with more regularity. “If you look back 75 years, nobody could afford to take a chance on certain titles, because there weren’t as many theatres… It was too much of a money proposition, their costs were too high,” he explains. But now, theatre groups are more willing to take chances and this means that some of the lesser known and appreciated works are getting an airing. Two Noble Kinsman, an oft-forgotten play usually attributed jointly to Shakespeare and John Fletcher about two cousins who fall in love with the same woman, for example, is being staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company this August. (Cohen noted, however, that he still hasn’t gotten into King John, a play that was hugely popular in the 19th century. The fact that it’s particularly concerned with mourning, a kind of national pastime in Victorian Britain, as well as its patriotic themes, probably goes some way in explaining its attractiveness then. “But for today, I think it doesn’t do the same things for us,” says Cohen.)

But are there still some plays that even a skillful director or soulful actor can’t lift, that even a sympathetic cultural context can’t make sense of? Well, sort of. “When we assume that Shakespeare is a universal genius, you can go too far and think that everything he did was great,” says Wilcox. She points to when in Othello, the title character flies into a murderous jealous rage so quickly it doesn’t seem believable. “Scholars have come up with all kinds of justification for this… Maybe Shakespeare was just way more interested in Iago and developing him in a three-dimensional human being, and sort of didn’t develop Othello. I think we should recognize Shakespeare’s limitations as well.”

Cynthia Lewis, the Dana professor of English at Davidson College in North Carolina, agrees – Shakespeare’s plays are good, she says, “But some are better than others.” For example, she recently taught Richard III, the story of villainous Richard’s machinations to become king and his short, tumultuous reign, written around 1592. It was written earlier in Shakespeare’s career, and “although he was a gifted dramatist from day one, he was learning the craft.” Said Lewis, “I found the plot really hard to follow, the characters hard to distinguish. Shakespeare is notorious for his complicated, multi-layered plots, but he got a lot better at putting them all together and enabling them to be followed… and creating characters with more dimension so that they could be followed clearly.”

So what else might land a play on the “bad” list? “I think a play that poses challenges of staging, almost insurmountable problems of staging that can’t be retrieved or rehabilitated or remediated, basically, through staging,” said Lewis. “I think that kind of play can be a talky play. I think for example Troilus and Cressida, it may be a better play on paper than on the stage because it is so heady and talky and torturous, and it’s surprising because its story is so vital… I do have a place in my heart for it, and I’ve seen a couple of productions, but even by the [Royal Shakespeare Company] it’s really hard to wrestle that play to the ground in the theatre.”

There are others, she says: Timon of Athens, for example, about a man who readily gives away his money to his unworthy friends only to find that once his funds run dry, so too does his stock of friends; he becomes bitter, hides himself away in a cave, and eventually dies miserable, having tried to make other people miserable, too. It’s a dark, downer of a play that doesn’t make it to stage that often. Likewise, some of the history plays, such as Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and 3, can be plodding and slow. Cymbeline, a rarely performed and totally bonkers play including lovers forced apart, cross-dressing, murder plots, mistaken identity, mistaken deaths, long-lost children, and treacherous villains, is another: “There’s everything but the kitchen sink in that play,” says Lewis. “ I think that a director might look at a script like that and say, ‘How am I going to deal with that?’” (We might also add to the characteristics of “bad” Shakespeare plays that their authorship is sometimes in question, although whether that’s a function of how invested we are in Shakespeare being a genius or of actual evidence of another writer’s hand is unclear; probably both.)

When The Telegraph and The Times asked their Shakespeareans about their favorite plays, they also asked about their least favorite plays. There were some significant overlaps in the most disliked, plays that appeared on both lists: The Taming of the Shrew, despite its many adaptations and performances, is perhaps too much misogyny disguised as comedy for modern audiences; Timon of Athens too bitterly misanthropic; Henry VIII too boring; and The Merry Wives of Windsor, the Falstaff spin-off sex romp, too silly and obviously hastily written. But The Telegraph’s list also includes some “classics”, including Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest, and The Merchant of Venice, possibly indicating hits fatigue. The Times ranking has more predictable entries, including Edward III, a dull play whose authorship is frequently questioned, Two Gentlemen of Verona, possibly Shakespeare’s first work for the stage, overly cerebral Pericles, All’s Well That Ends Well, with its awkward happy ending, Two Noble Kinsmen, which includes Morris dancing. And yet, even critical dislike isn’t enough to keep a weak Shakespeare off the stage – all of these plays have their defenders, and companies willing to take a chance on a new, innovative, possibly outré staging. So perhaps the best way to sum up attempts to rank Shakespeare is with a line from the Bard himself: Quoth Hamlet, “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)