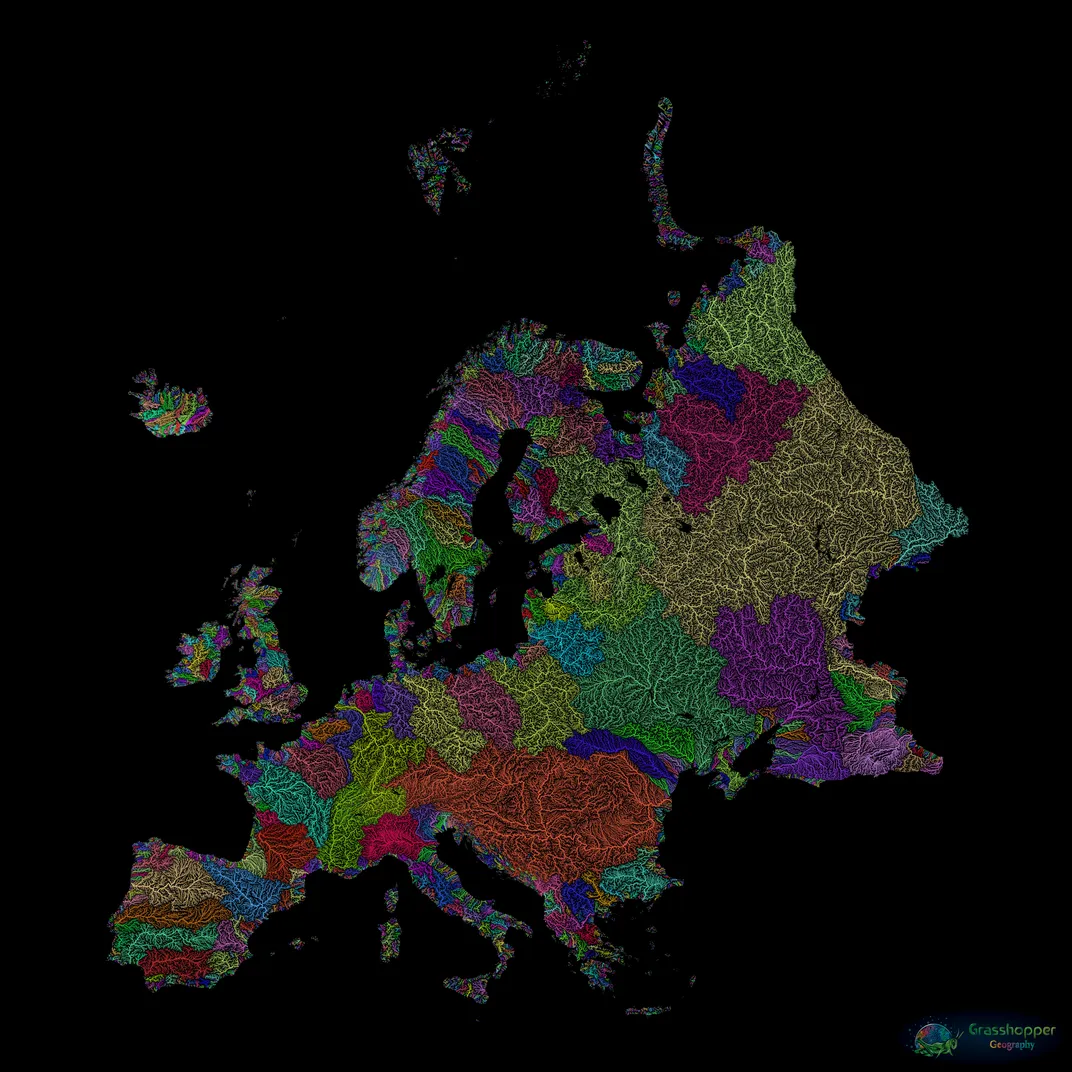

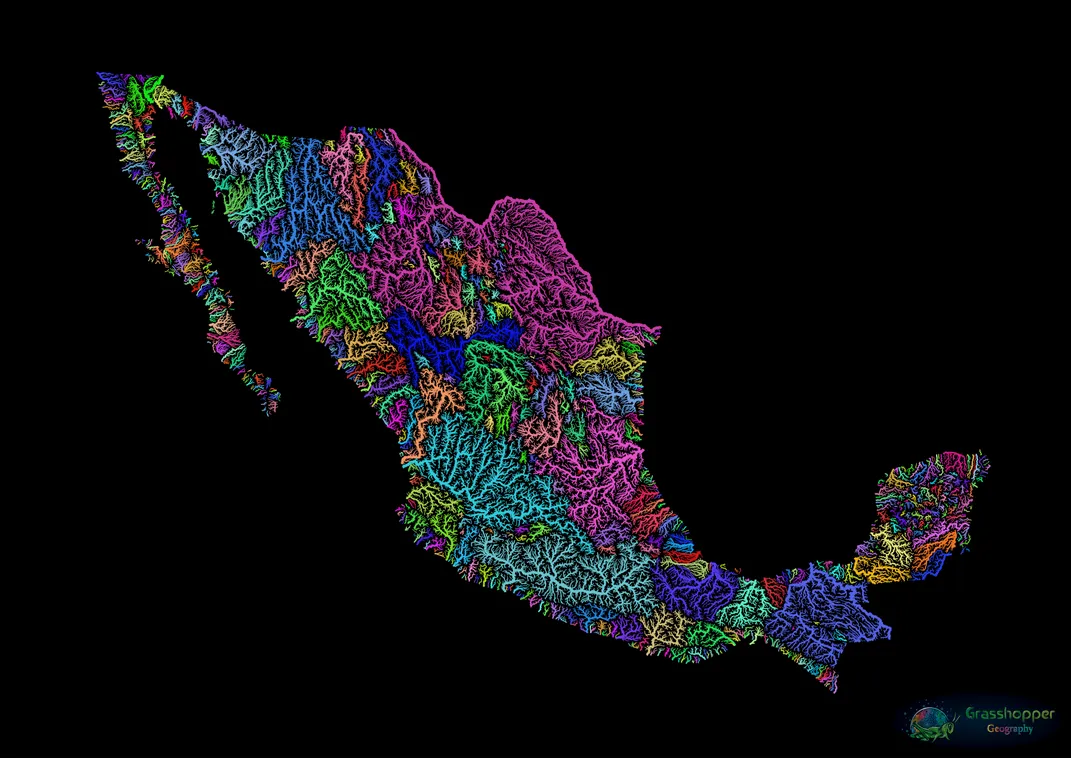

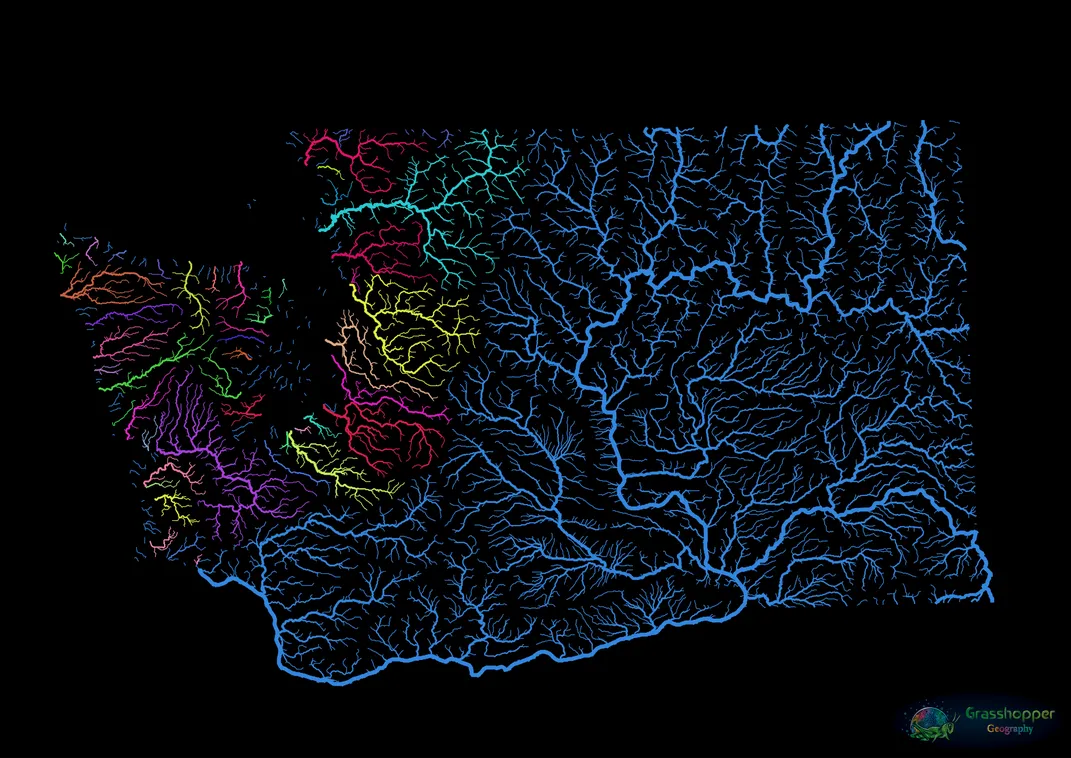

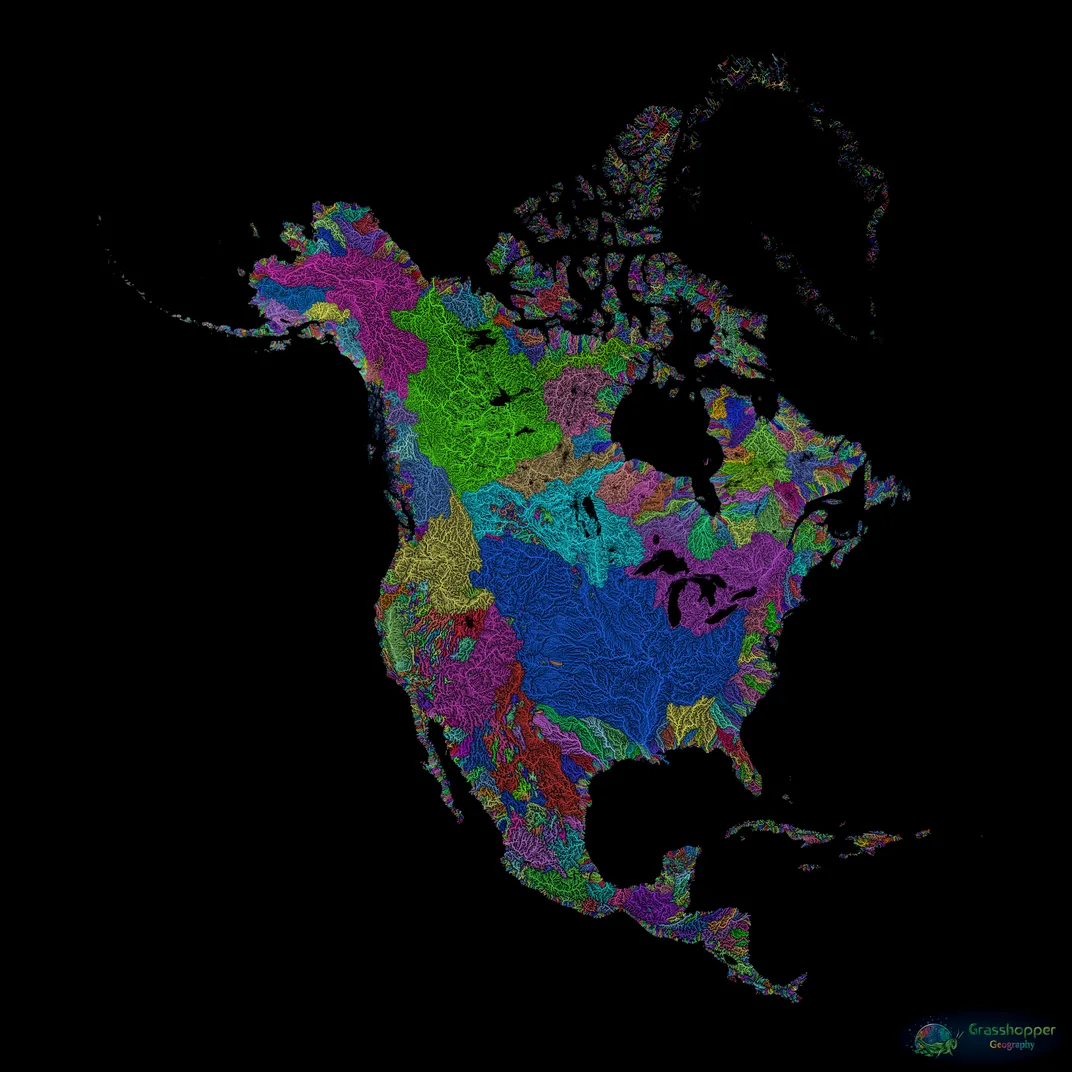

These Beautiful Maps Capture the Rivers That Pulse Through Our World

Cartographer Robert Szucs creates colorful maps of the watersheds that creep across states, countries, continents and the globe

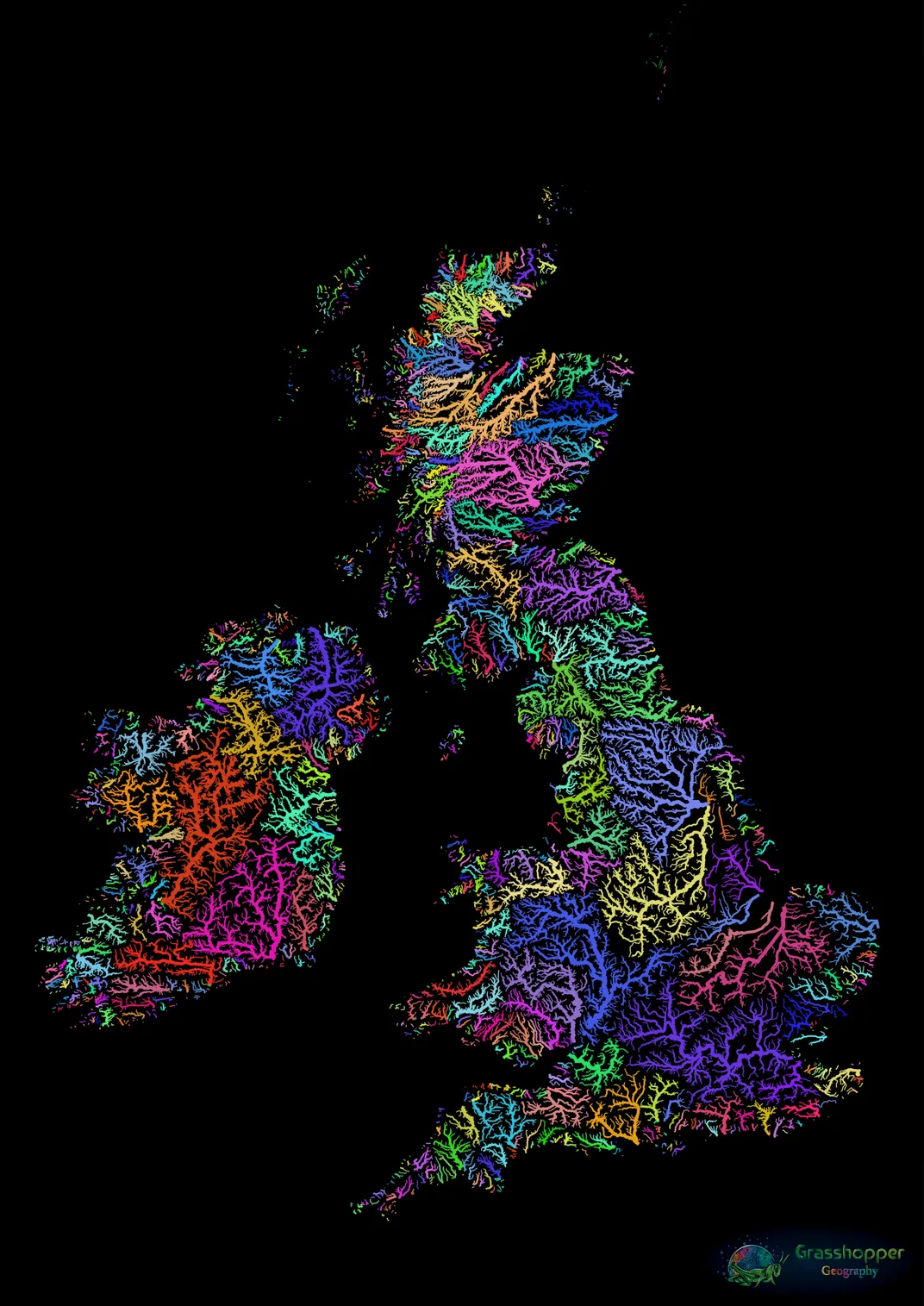

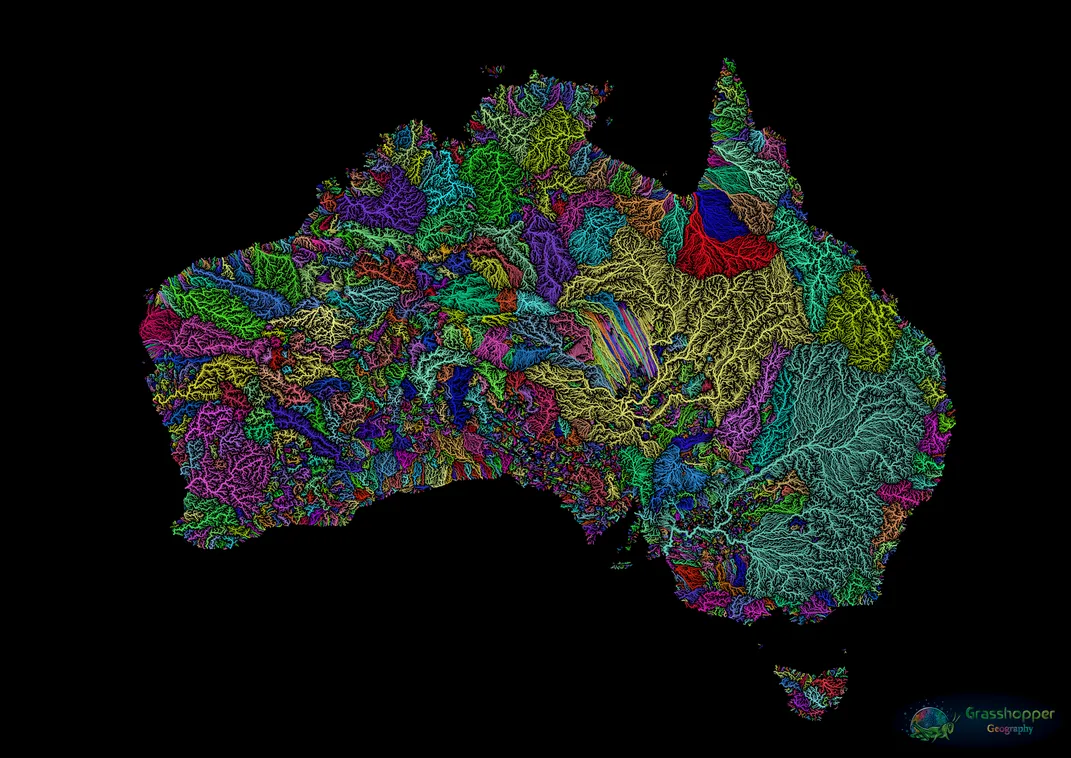

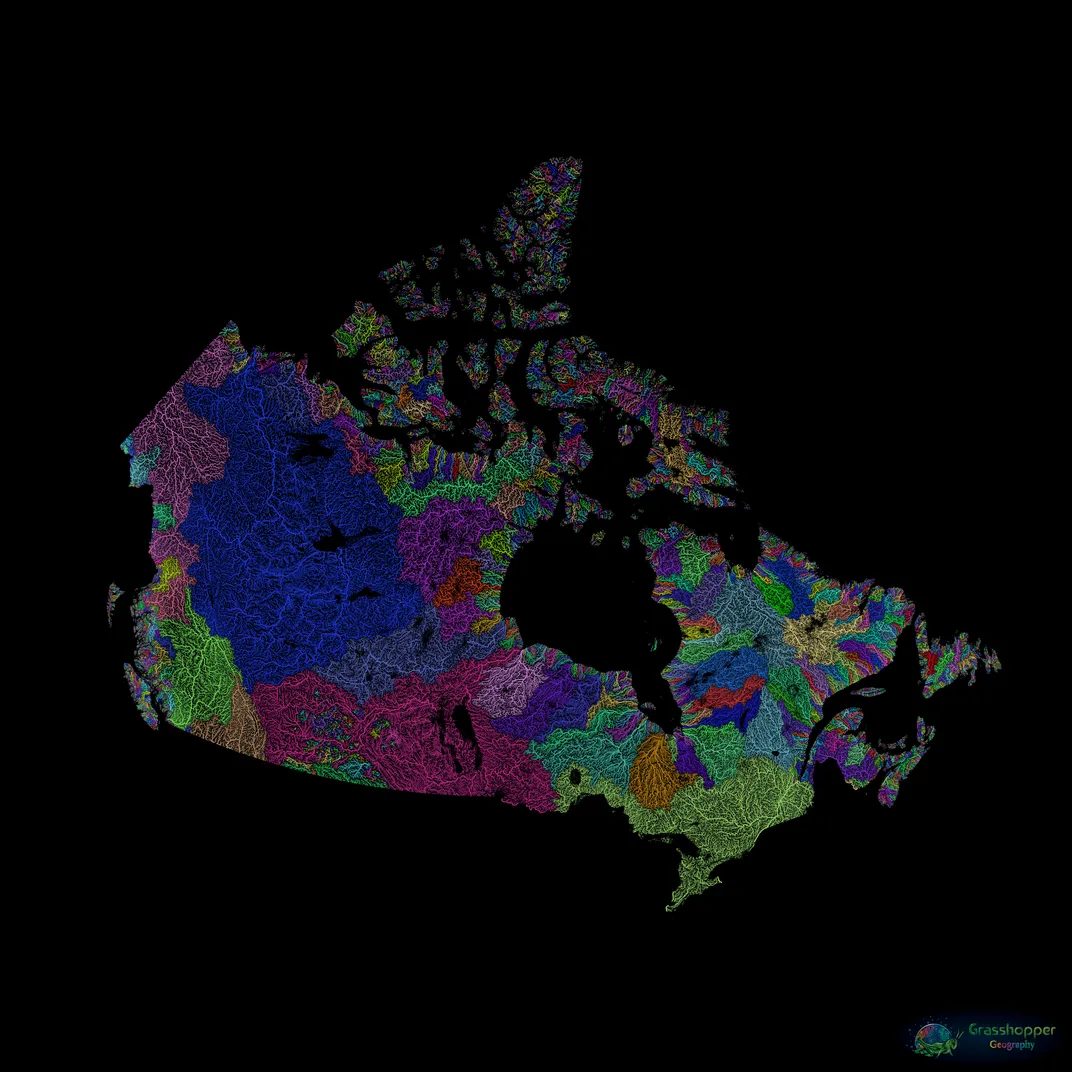

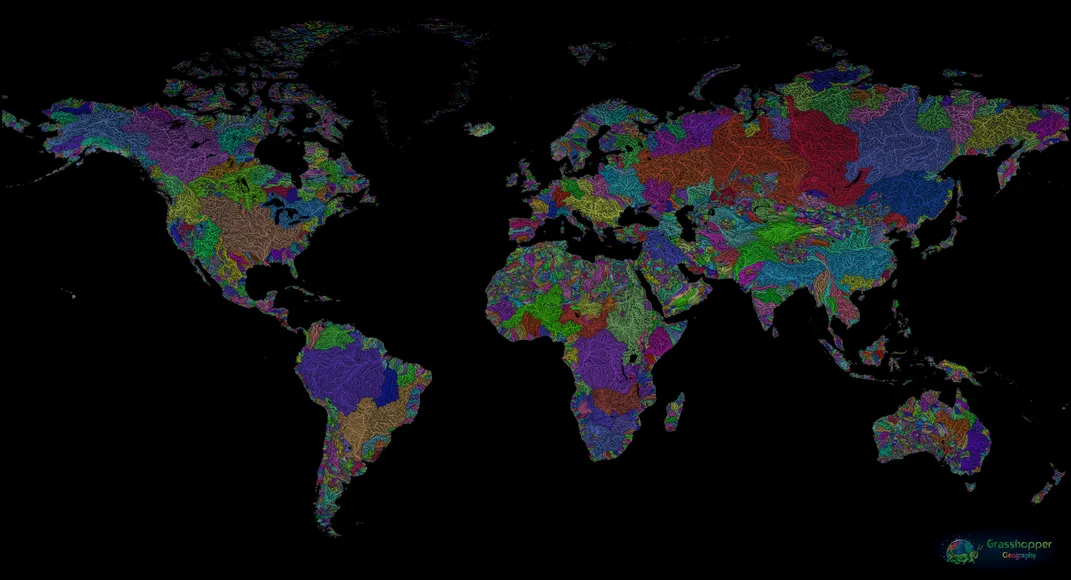

A rainbow of tiny furrows spreads across a map of the contiguous United States, the lite-brite hues popping against a black backdrop, giving the appearance of roots or a vascular system.

To the casual observer, this is undeniably a work of art. But the image’s creator, Hungarian cartographer Robert Szucs, sees his work as primarily scientific. “You can call me an artist if you insist, but it still makes me smile a bit,” says Szucs. “I’m definitely still getting used to that.”

Rather than art, Szucs has a background in digital cartography and geographic information system (GIS) analysis. With a master’s in geography and GIS from the University of Szeged, Szucs has used these skills for everything from mapping orangutan movement and changes in Indonesian forest coverage to monitoring whale behavior in Alaska. “GIS is a collective name for all things geographic, spatial and mapping related,” he explains. “It's basically a tool set, and I've used it for widely different things.”

Szucs didn’t make artistic maps until a decade into his cartography career. While volunteering at a marine environmental research NGO in Portugal, he began to experiment in his free time with open-source software commonly used by cartographers to generate data visualizations. Through trial and error, Szucs learned how to create maps that are both informative and visually striking. Szucs works under the alias “Grasshopper Geography,” a reference to his Hungarian nickname, “Szöcske,” which translates to grasshopper.

The majority of Szucs’ maps depict expanses of land sectioned off by watersheds, the areas of land that comprise the drainage systems channeling rainwater from creeks to rivers to oceans. The cartographer found existing river maps uninspiring, and decided to use satellite data based on digital elevation models to create his own. “I’ve had this feeling for quite a while when looking at river maps, that maybe I could do better,” says Szucs. “I wanted to do justice to the beauty of rivers.” Szucs’ maps show the watersheds in a way that is both elegant and informative—though his color use is primarily an aesthetic choice, the variation in hues delineates different watersheds with scientific accuracy, with each color corresponding to a continuous river system. For example, on his map of the United States, the pink spider-webbing across nearly half the country represents the massive Jefferson-Mississippi-Missouri River system, which includes, of course, the parts of the Missouri and Mississippi river basins that are experiencing catastrophic flooding right now.

According to Matthew Ross, an assistant professor with Colorado State University’s Department of Watershed Sciences, the bright colors highlight key factors of watershed morphology. “Watershed size and shape can control a lot of important hydrologic and biogeochemical functions of rivers,” says Ross. “The maps show the real variation in the world of watershed sizes well.”

Szucs’ maps lack the sterility common in data visualizations—though scientifically valuable, they are filled with personal connection. His favorite maps are of places that hold deep meaning for him. “South Africa,” he says, “where I first moved from my parents’ house. Alaska, where I spent two summers, and where my soul is at home.” So far, Szucs has created 156 maps showing watersheds and river systems across the globe, ranging in scale from singular states to an entire seven-continent expanse. In addition to water systems, Szucs has also mapped forest coverage, and intends to attempt city streets as his next endeavor.

Though never displayed in a gallery setting, Szucs’ maps have received international attention. After posting the works on Etsy in 2016, Szucs was inundated with responses from individuals captivated by the colorful maps.

“My maps reveal that I was right to think you could do justice to the beauty of nature in a scientific way,” says Szucs. “They are important because they inspire millions of people to go out and appreciate nature more.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnnaWhite.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnnaWhite.jpg)