These Delicate Images of Seaweed Were Captured Using a Flatbed Scanner

In a new book, photographer Josie Iselin highlights the exquisite colors and forms of kelp and other marine algae

It is hard to ignore the weed rooted in the word "seaweed," especially when the marine algae is known to be a bit of a nuisance. Swimmers can get tangled in seaweed, and when it bakes in the sun, it can make a once-pleasant beach smell rancid.

But photographer Josie Iselin finds the beauty in seaweed. For her new book, An Ocean Garden: The Secret Life of Seaweed, the San Francisco-based artist and regular beachcomber captured more than 200 specimens—giant kelp, sea lettuce, bladderwrack, green rope, sea grapes, cat's tongue and Turkish towel, to name a few—using a flatbed scanner.

Viewers will surely be taken with the vibrant colors. "Color is perhaps a seaweed's most striking characteristic," writes Iselin. "When held up to the light, the intensity of its magenta, the subtlety of its golden brown, or the clarity of its kelly green can take your breath away."

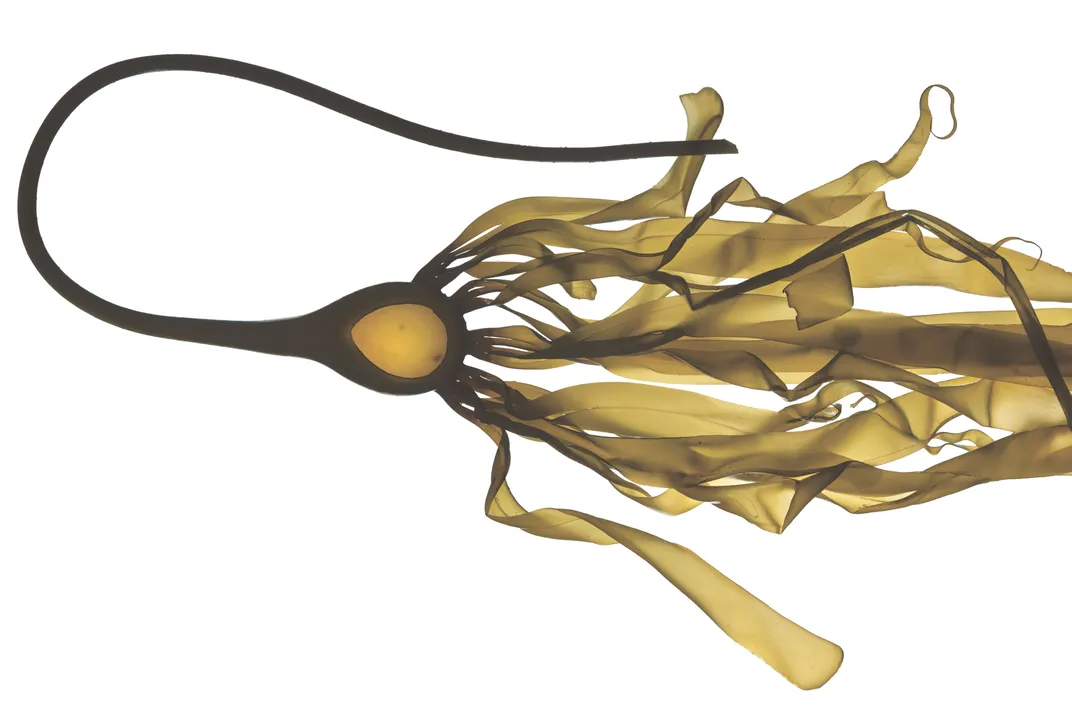

The specimens are elegant in form. "From tiny and intricate to enormous and singular, the diverse shapes found among the tangle of seaweed at the ocean shore are all strategies to confront the three tasks essential for success in the intertidal zone: holding on, gathering light and nutrients, and defending against being eaten," she adds. Giant kelp, for instance, has ovoid bladders that—"like tiny buoys," says Iselin—cause it to float, optimizing the exposure to sunlight needed for photosynthesis.

Seaweeds are efficient machines, generating about 20 percent of the oxygen in our atmosphere. And, humans have put the marine algae to use in a number of ways. For example, seaweed contains natural gelling agents that give things like shaving cream, toothpaste, salad dressings and ice cream their consistency.

I recently interviewed Iselin about her interest in seaweed, and she shared some thoughts on how this photographic series came to be:

First and foremost, why seaweed?

Seaweed is extraordinarily beautiful, profoundly interesting and important, and so few people know this.

How did this project get its start? What was the first bit of seaweed that you collected and scanned, and from where did you collect it?

In 2009, I was working on a book titled, Beach: A Book of Treasure. I wanted to include a range of treasure found at the beach, from sand to sea glass, driftwood to fossils and beyond, to human detritus. When out on a reef north of San Francisco, I happened to hold a scrap of seaweed up to the sky and was startled by the intensity of color—magenta—and the fabulousness of form.

Right then and there I knew I had to get some seaweed specimens back to my studio to capture on my scanner. A second investigation involved a small bull kelp washed up on a local San Francisco beach. When I was able to capture the dynamic quality of its blades, or fronds, I knew I had to continue. An Ocean Garden evolved from there.

In the book, you mention having a foot in both the East and West Coasts. Where specifically do you search for seaweed?

I spend a good portion of each summer in Penobscot Bay, Maine, where the Atlantic waters are gentle and the rocky shore is dominated by rockweed, or Ascophyllum nodosum, and bladderwrack, or Fucus vesiculosus. There is no need to collect, just to go down to the beach and look closely at something so ubiquitous as to be overlooked!

Here, in my home of San Francisco, I walk on a beach called Fort Funston twice a week. The winter storms wash up huge mounds of bull kelp and other seaweeds. Again, there is plenty to observe and appreciate right there on the beach.

You tell stories about where, when and how you found particular seaweed specimens. What do you enjoy about the collection process?

Learning about seaweed is absolutely tied to my love for being on the beach, that strip of land that connects us to the ocean. It is a place of discovery about our natural world and also a place of self discovery and rejuvenation. My journey into the science of seaweed has made me more aware of the extraordinary variabilities of life in the intertidal zone. Imagine having the basic fabric of life—the ocean—torn away and come flooding back twice a day!

Are you partial to certain species? If so, which ones, and why?

My favorite seaweed is the feather boa kelp, or Egregia menziesii, which is common in the low intertidal zone of our Northern California coast. It should be the state seaweed of California. It can grow 25 to 35 feet in just a few months, and it has beautiful paddle-shaped blades that radiate off a long strap-like center rib. It also has these adorable bladders that sport whimsical blades at the top.

Can you take me through your artistic process? How do you make a scan?

I put the specimens on my scanner either wet or dry. I built the book as I went along, like a piece of sculpture. The book is visually driven, so the text is illustrating or working in concert with the sequencing of the imagery.

What is your goal in creating these images?

I think of these images as portraits celebrating that particular specimen. None of my work is about the rare or spectacular, but it is very much about how the mundane or common can truly be spectacular. Seeing the unseen is a common thread.

What do you find artistic about seaweed?

Seaweed provides a fantastic nexus where art and science can come together. The images—their beauty and vast range of forms—draw you in and kindle specific questions. Why is it that extraordinary color of pink? And, the biology of their life cycle, success in the intertidal zone and their importance to the ocean ecosystem makes us change orientations, consider new possibilities.

In the book, you combine the images with a great deal of scientific fact. What has been the most interesting thing that you've learned about seaweed?

Seaweeds are not plants. Plants evolved from some ancient green seaweeds—it is where they get their green chlorophyll—that migrated up from the shore onto the land, but the relationship stops there. Unlike terrestrial plants who have to combat gravity at all times, seaweeds use the buoyancy of the ocean to keep their fronds up towards the sun, so they can put all their energy into transforming sunlight and carbon dioxide into organic material. Some kelps can grow as much as 60 feet in a single season. They can grow very fast, up to ten inches a day!

Due to a range of pigments housed in their chloroplasts—green, red, blue or brown—seaweeds and kelps can be a fantastic range of colors, from brilliant pinks and purples, to olive and orangey brown to bright kelly green. These pigments have evolved to collect different wavelengths of light that filter through the ocean waters, light needed to photosynthesize efficiently.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)