These Eerie Portraits Capture Endangered and Extinct Animals in a Film That Is Also Vanishing

Denis Defibaugh uses Polaroid 55 film to give animal specimens an afterlife

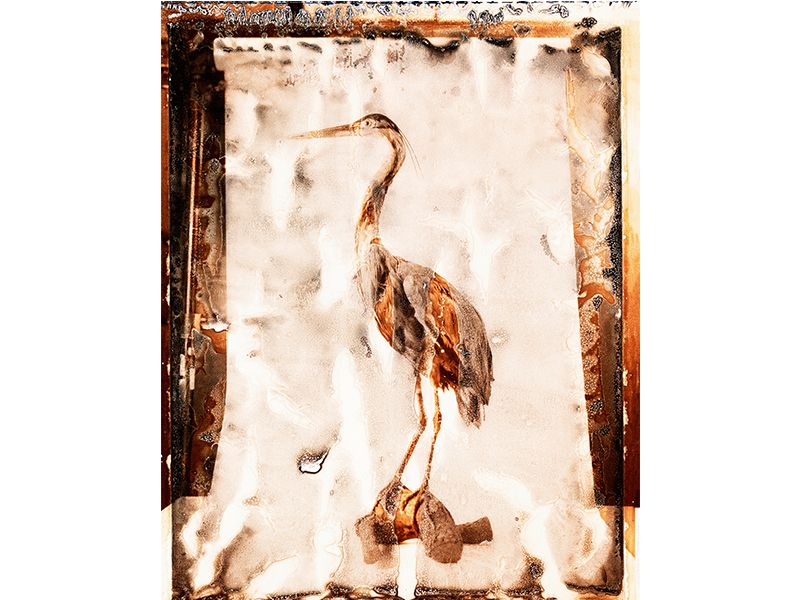

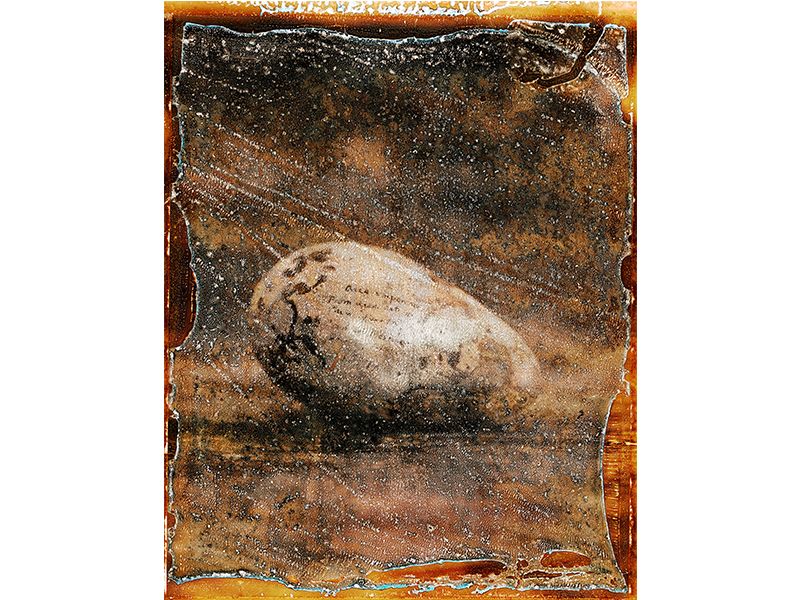

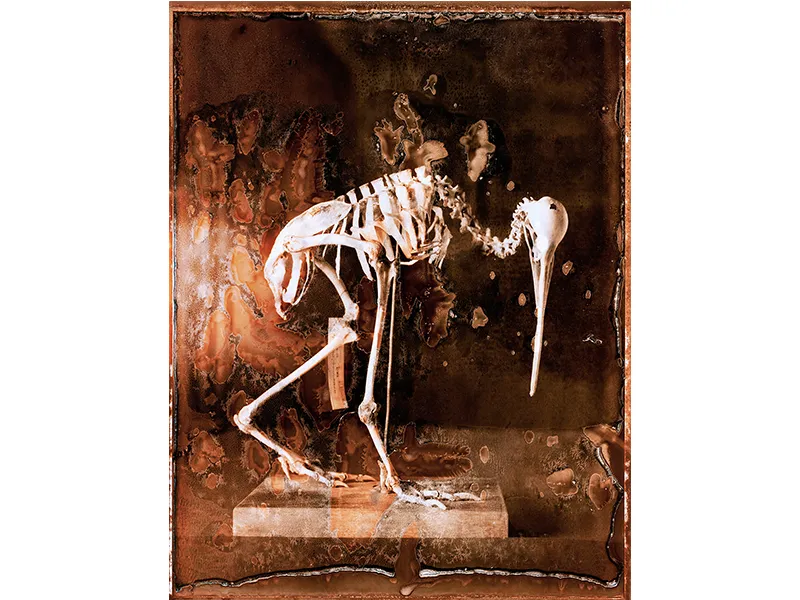

The Labrador duck, the great auk and the passenger pigeon—they are long gone, extinct for well over a century. But photographer Denis Defibaugh has been training his lens onto zoological specimens in natural history museums across the country, bringing them to a new, eerily beautiful life in his “Afterlifes of Natural History” project.

The Rochester, New York-based artist focuses on critically endangered and vanished birds, insects and mammals, hoping to call attention to their plight and sound a warning about the ongoing demise of many species. He first began to photograph specimens in the natural history museum at Zion National Park in 2003 while on sabbatical from his job as a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). Since then, he’s done portraits of nearly 100 animals.

“The specimens are beautiful to look at, finely crafted art, as well as a historical artifact that reminds us how fragile life is,” he explains.

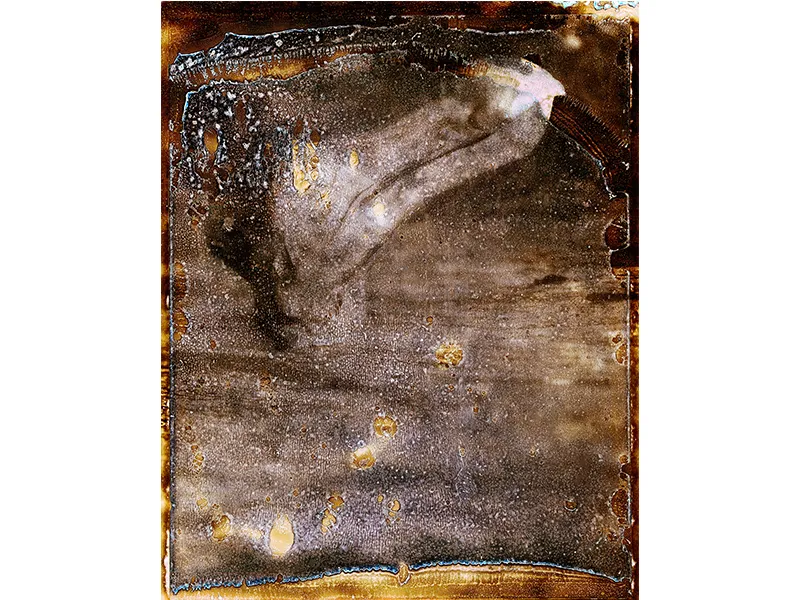

Since then, Defibaugh has been on a quest in the spirit of the great naturalists—he considers painter-ornithologist John James Audubon an important influence on his work—to capture rare specimens in the collections of Chicago’s Field Museum, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Doing so with Type 55 film—a film nearly a decade out of production—and a technique that digitizes the negatives as they continue to develop and decay into blackness seemed only fitting.

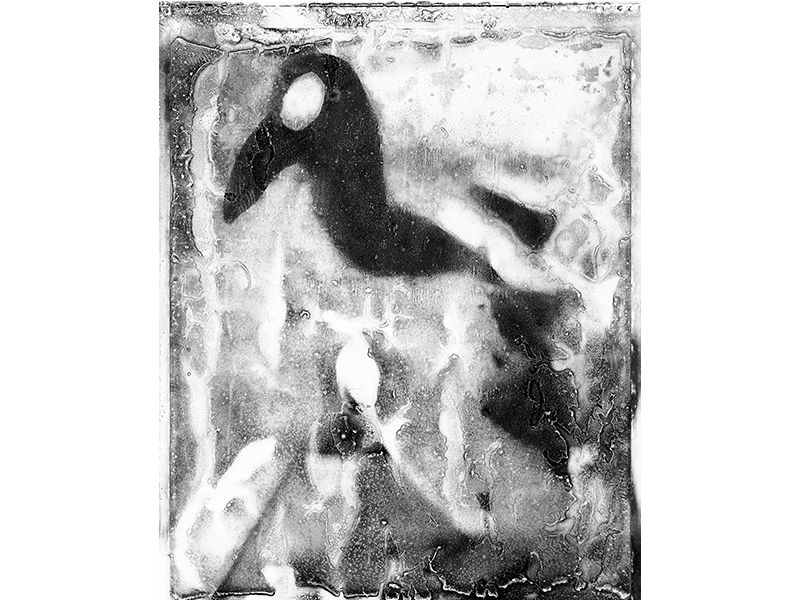

First released in 1961, Polaroid Type 55 is a black and white, 4x5 film that creates both a positive print and a negative. They are framed by distinctive mesh-like rows of dots on one side and sharp edges on the other three, offering the “organic-distressed aesthetic that I was looking for,” says Defibaugh.

His medium, however, has become as endangered as his subjects after Polaroid ceased production of its instant films in 2008 during its second bankruptcy. Only eight boxes remain in Defibaugh’s personal stash (he once purchased a case off a photographer friend), stored away safely in a refrigerator.

When processing the film he is more laissez-faire, relinquishing control over the negative’s development to chemistry by diverging from Polaroid’s recommended method.

In Type 55, photographic receiving paper and a light-sensitive negative film are sandwiched together in a sleeve with a reagent pod, a packet of chemicals with a gel-like consistency, at one end. After exposure, the photographer pulls the sleeve through a pair of metal rollers that squeeze open the pod and spread a mix of a rapid developer, a silver solvent and other chemicals evenly between the sheet and negative.

What follows in the next minute or so of development (the exact time depends on the ambient temperature) is a bit of a mystery, as Polaroid’s processes were proprietary. What’s known is that it is a diffusion transfer process, in which light-exposed silver remains immobilized in the negative, and unexposed silver halides (or silver salts) move from the surface of the negative to the receiver layer of the print side. There they react with chemicals to form the positive image in black metallic silver.

When the time is up (Defibaugh waits an extra minute for better contrast), the photographer peels apart the Polaroid to reveal a black and white print and a negative. The print typically receives a brushing of protective polymer coater fluid, while the negative is treated first in a sodium sulfite solution that removes any remaining chemicals, then a water bath and finally a fixative that prevents damage to the fragile gelatin surface.

“Wash and dry and you have a beautiful full-tone negative that will produce fine black and white prints,” says Defibaugh.

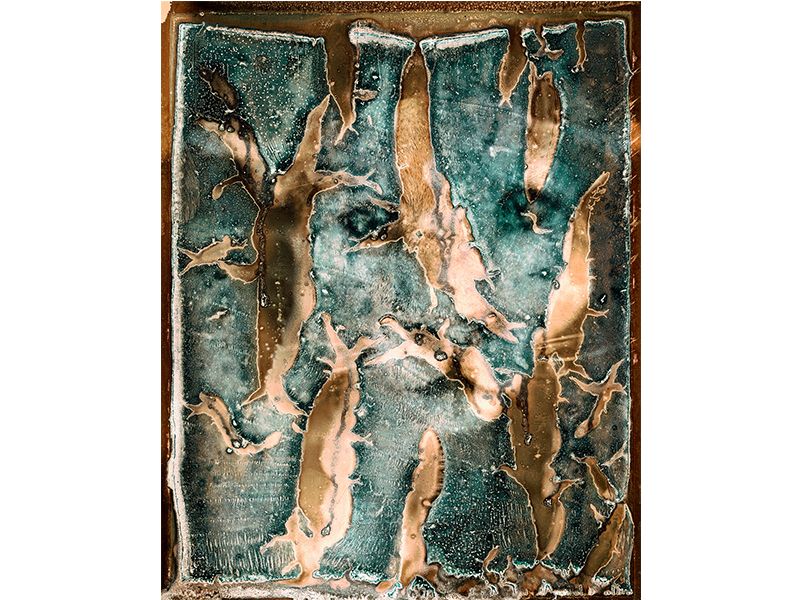

To turn Polaroid’s finely tuned efficiency into organic art, however, he diverges from this protocol by skipping the post-development clearing process. Instead, he allows “all those residual chemicals and byproducts to stew on the negative and together with air pollutants attack the silver and the gelatin binder in which it is suspended,” says Alice Carver-Kubik, a photographic research scientist at RIT’s Image Permanence Institute who is familiar with Defibaugh’s work.

She attributes thick crystalline deposits to lingering chemicals from the reagent pod, while bubbles and channels are due to the gelatin buckling up from its plastic support, giving the negative a tactile surface. Remaining anti-halation dyes (that keep light from refracting during exposure) are responsible for a dark gray cast, layered with yellow from the deteriorating gelatin.

Because Defibaugh places the dried negatives into sleeves, they oxidize in ways typical for photographs mounted in books or in stacks as air seeps in from outside, Carver-Kubik points out. “When scanned, many of them show colors in the range of blue and orange around the edges and in some cases more heavily along the top and sides, as in the Labrador Duck,” she says, comparing the tones to those seen in daguerreotypes.

“I watch this process and scan the negative in RGB [color] once the film has degraded and developed to a patina, crystallized, layered look after about 6 to 12 months,” Defibaugh explains. The negative will continue to decay into total blackness.

Capturing the images with the very digital technology that contributed to the demise of the Polaroid instant films and company is just one of the many ironies of the “Afterlifes” project. Take the specimens themselves, which are, according to Defibaugh’s artist statement, “wrought with contradiction.”

To create a specimen, animals are sacrificed, but their prepared bodies may continue to exist almost indefinitely, given ideal storage conditions (some of the Smithsonian’s specimens date back to the 1800s.) In their new form, the deceased animals give life to scientific study, notably of biodiversity.

“This collection is a biodiversity library,” says Christina Gebhard, a museum specialist in the National Museum of Natural History’s division of birds, who served as Defibaugh’s contact. “Each specimen is essentially a snapshot in time.”

Defibaugh captures not only one moment in each specimen’s existence, but later, digitally, that image’s deterioration. “(This) duality of preservation and decay is at the crux of these photographs,” says Defibaugh, who hopes to continue his project at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History as well as the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Gebhard, for her part, is happy that Defibaugh is bringing the rarely seen Labrador duck or great auk before a wider audience, especially those who may not be confronted with biodiversity loss in their everyday lives.

“People can make a quick connection between his choice of a short-lived medium and the extinct species that faded away before we had any concept of conservation,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Olivia_M._Hall.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Olivia_M._Hall.jpg)