These Photographs Capture the Complexities of Life at Guantánamo

In a new book, photographer Debi Cornwall casts the naval base as “Camp America”

American documentary photographer Debi Cornwall approached her latest subject, U.S. Naval Station Gauntánamo Bay, with one question. What does it look like in a place where no one has chosen to live?

Established in 1903, “Gitmo,” for short, is the oldest overseas installation of the United States military. The base in Cuba is where the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet is stationed, and a prime location for assisting with counternarcotic operations in the Caribbean. But it is perhaps most known in recent times for its detention camp established by President George W. Bush during the buildup of the "War on Terror” post 9/11.

Roughly 11,000 military personnel live at Guantanamo Bay. A special Joint Task Force guards the 41 current detainees (of the more than 700 in the camp’s history). Beyond that, there are family members, U.S. government civilians and contractors, and third-country nationals.

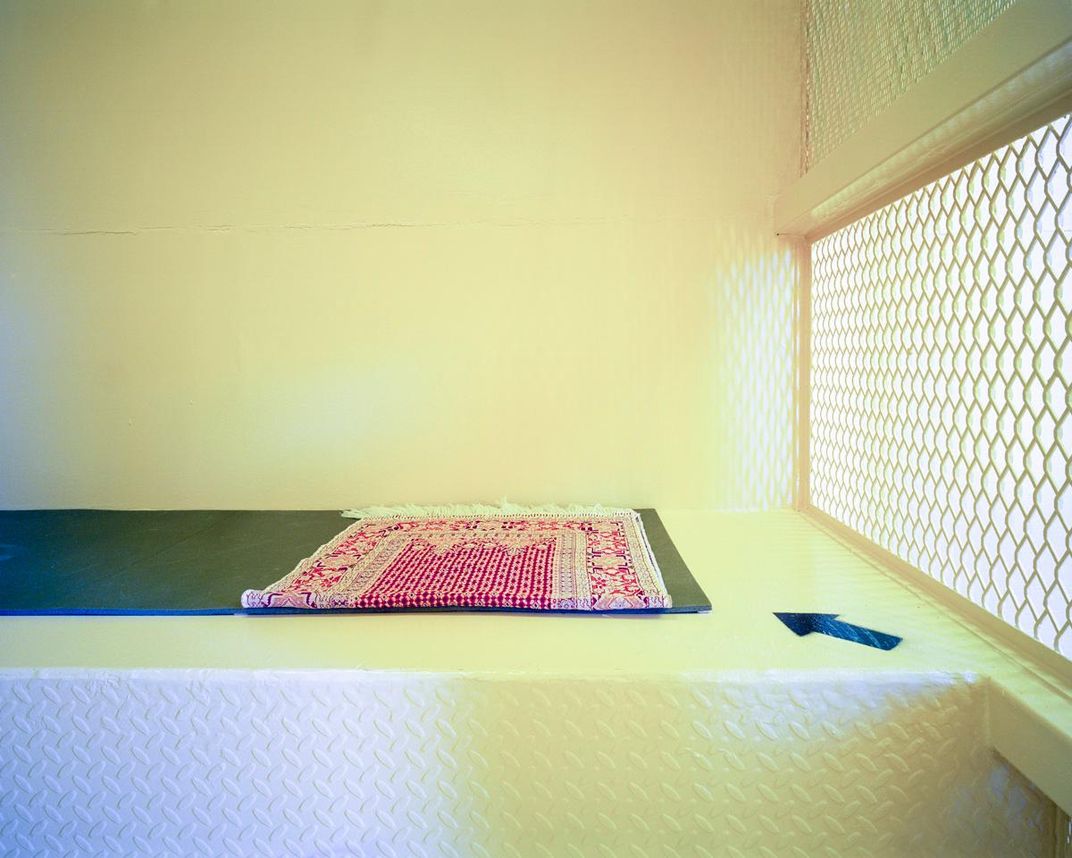

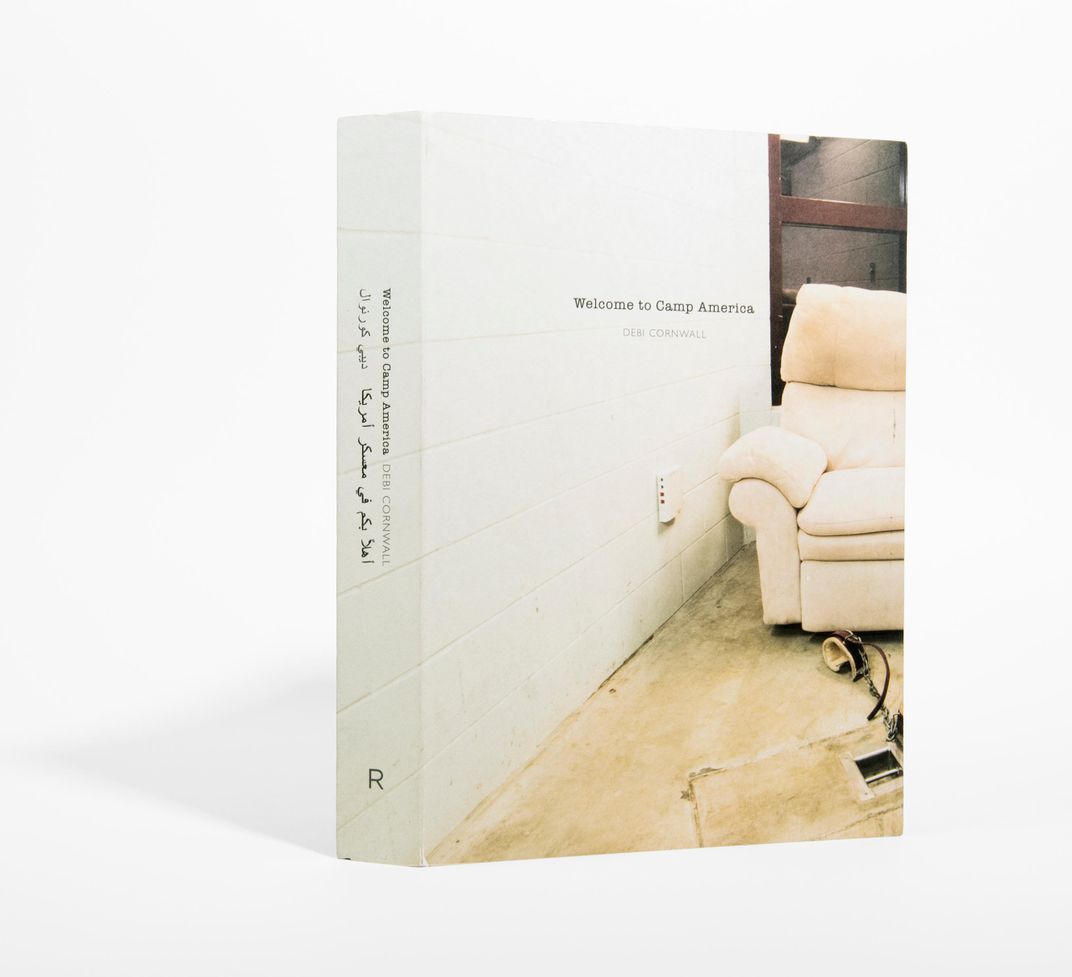

In her new book Welcome to Camp America, Cornwall gives a multi layered look into the complexities of life at Gitmo. The central text is a guard’s detailed account of being mistaken as a prisoner and subjected to violent torture tactics. Cornwall continues to show Gitmo’s dark side in images of its facilities, once-classified documents justifying torture, and a guard’s confession of a botched training exercise that was covered up. But all of this is juxtaposed with photographs of peculiar objects for sale at the Gitmo souvenir shop, and the residential and leisure spaces frequented by prisoners and guards—a bowling alley, beautiful beaches.

One jarring souvenir, a crop top with a graphic stating, “Guantanamo Bay, It don’t GTMO better than this,” captures the bizarre truth of the place: For some, it’s paradise, and for others, it’s hell.

Portraits of detention camp survivors, most of whom never had charges filed against them, are positioned throughout the book as removable inserts. The placement of these inserts serves as metaphor for the way in which these individuals have been relocated throughout the world; displaced to countries that they’ve never called home and often where a language unknown to them is spoken.

Cornwall, who spent 12 years as a wrongful conviction lawyer, casts a critical, deliberate eye on a controversial setting in recent American history. A disturbing look into the naval station, the book can leave you with more questions than answers.

What initially made you want to go to Guantánamo Bay?

My interest in Guantanamo Bay grew out of my work as an attorney. I was a civil rights lawyer for 12 years representing innocent DNA exonerees and lawsuits in the United States. So when I stepped away from litigation in 2013 and was looking for a project to come back to photography, I first thought I'd like to make portraits of men cleared and released from Guantánamo. The challenges they're facing are very similar to the challenges facing my former clients, but of course much more complicated.

Can you talk about the process it took to visit Gitmo, and your initial reaction?

It was a challenge to find out who to ask for permission to visit as an independent photographer not sponsored by a magazine or supported by an institution. Once I found who to apply to, I wrote up a proposal asking for permission to visit Guantanamo to photograph daily life of both detainees and guards. It took eight or nine months and a background check, but I heard back that I was going to be allowed to visit. Ultimately, I visited three times over the course of a year.

My immediate reaction was that this feels like an uncannily familiar place. It feels very American, yet it’s on Cuba. And at the same time, there ae two very different worlds within the military base. There is the naval station that has been there for over 100 years where the morale, welfare, and recreation department does everything it can to make sailors and soldiers feel at home. And since January 11, 2002, there are the War on Terror prison facilities that are housing, at this point, 41 men without criminal charges or trial. I don’t know if they ever will get released. But there was a real sense of a jarring disconnect, even as it felt very familiar.

How does your background as a civil rights lawyer inform your visual work?

As an attorney, I was looking at the big picture – what went wrong in the criminal justice system – and the very personal impact of those lapses on individuals, their relationships and communities. As a visual artist, I bring the same dual focus on the systemic and the intimate to my work.

Were you surprised by the gift shops?

Nobody expects to see a gift shop in a place best known for its prisons. But on the other hand, it’s a very American thing to make sense of something through a souvenir, something you can buy and take home. So, I bought a number of objects and brought them to photograph for the book.

What was your intention of having the former detainees face away in the portraits made of them?

I am replicating, in the free world, the military-imposed rules for making photographs at Gitmo: no faces. In essence, I'm photographing them as though they were still there. For many of them, especially those transferred to third countries, that's how they feel.

If there is one thing you’d like the viewer to take away from Welcome to Camp America, what would that be?

I hope that readers have a visceral reaction to this work, that they will be surprised and curious to learn more. It’s really inviting viewers, no matter what their worldview, to sit with the question, “what do we have in common?”

Welcome to Camp America has been shortlisted for the Aperture Paris Photo First PhotoBook Prize. Meanwhile, an exhibition of the work, “Debi Cornwall: Welcome to Camp America, Inside Guantánamo Bay,” is at Steven Kasher Gallery in New York through December 22. You can follow Debi Cornwall on Instagram @debicornwall