The Women Who Coined the Term ‘Mary Sue’

The trope they named in a ‘Star Trek’ fan zine in 1973 continues to resonate in 2019

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/13/fe13d0d2-cbb5-4f2b-8f1a-37c4201898a9/marysue.jpg)

Soon after Paula Smith and Sharon Ferraro launched one of the earliest “Star Trek” fanzines, they started noticing a pattern to the submissions they were receiving. Each began the same way: a young woman would board the starship Enterprise. “And because she was just so sweet, and good, and beautiful and cute,” Smith recounts, “everybody would just fall all over her.”

Looking back, Smith says, it was obvious what was going on: “They were simply placeholder fantasies,” she says. “And, certainly, I can't say I didn't have placeholder fantasies of my own.” But the thing that had attracted the two friends to “Star Trek” was that the show—which had gone off the air for good in 1969, four years before they launched their zine—was intelligent. These submissions, says Smith, were not intelligent.

“There were very good stories coming out at that time,” adds Smith, who is now 67. “But there was always a huge helping of what we started calling in letters to the editors of other zines, a Mary Sue story.”

The “Mary Sue” character, introduced in 1973 by Smith in the second issue of Menagerie (named after a two-parter from the show's first season), articulated a particular trope that exists far beyond the “Star Trek” universe. Mary Sues can be found throughout the history of literature, standing on the shoulders of earlier fill-in characters, like Pollyanna, the unfailingly optimistic protagonist from Eleanor H. Porter’s children’s books from the 1910s. More recently, cousins to the term can be found in the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, as coined by Nathan Rabin in his review of the Cameron Crowe film Elizabethtown, and the Jennifer Lawrence-personified “Cool Girl.”

It’s no accident that all of these examples are women. Smith and Ferraro also threw around terms like Murray Sue or Marty Sue when they corresponded with editors of other zines, but male fill-in characters, it seemed, could be brave and handsome and smart without reproach. “Characters like Superman were placeholders for the writers, too,” Smith points out. “But those were boys. It was OK for [men] to have placeholder characters that were incredibly able.”

Women, on the other hand, were called out when their characters veered toward Icarus-level heights. It's not a surprise that as the term caught on, fans—often men—began weaponizing the Mary Sue trope to go after any capable woman represented on page or screen. Consider, for instance, the reaction to Arya Stark on the final season of “Game of Thrones.” Internet commentators refused to accept that of all the characters in George R.R. Martin’s universe, she emerged as the savior of Westeros. Despite having trained for that moment since the first season, when Arya killed the Night King, she was suddenly slapped with the Mary Sue label. What made the situation on "Game of Thrones" especially frustrating was that the show already had character that fit the mold of a Murray Sue, the forever meme-able Jon Snow. (Perhaps the most meta takedown of the incident came from Rachel Leishman, who asked “How in the World Is Arya Stark a Mary Sue?” in the publication the Mary Sue, a feminist website founded in 2011, which, among other reasons, intentionally took on the name Mary Sue to “re-appropriate a cliché.”)

When Smith and Ferraro founded Menagerie, the culture of the fan-made publication was a powerful force within the science fiction fan community. The fanzine had actually been born out of the sci-fi scene; the Science Correspondence Club in Chicago is credited with producing the first fanmag back in 1930, and later on, it was a sci-fi fan who coined the term “fanzine.” In the pre-internet days, these fanzines, or zines, for short, made for and by fans, became instrumental in growing fandoms and spreading ideas like the Mary Sue across the country, and even around the world. “[F]or almost forty years Fanzines were the net, the cement which kept fandom together as an entity,” longtime sci-fi fan zine writer Don Fitch reflected in 1998.

It helped, too, that Smith and Ferraro were already active members of the Trek community when they launched Menagerie in '73. Though nearly four decades have passed since they edited their final issue, both can still vividly recall the submission that inspired Mary Sue. The piece, which came in at 80-pages, double-sided, centered around a young protagonist who was, of course, brilliant and beautiful and ultimately proved her mettle by sacrificing her own life to save the crew—a tragic moment, which was then upended when she resurrected herself. “I’d never seen that one anywhere else,” Smith says with a laugh. “So, I have to give [the writer] kudos for that.”

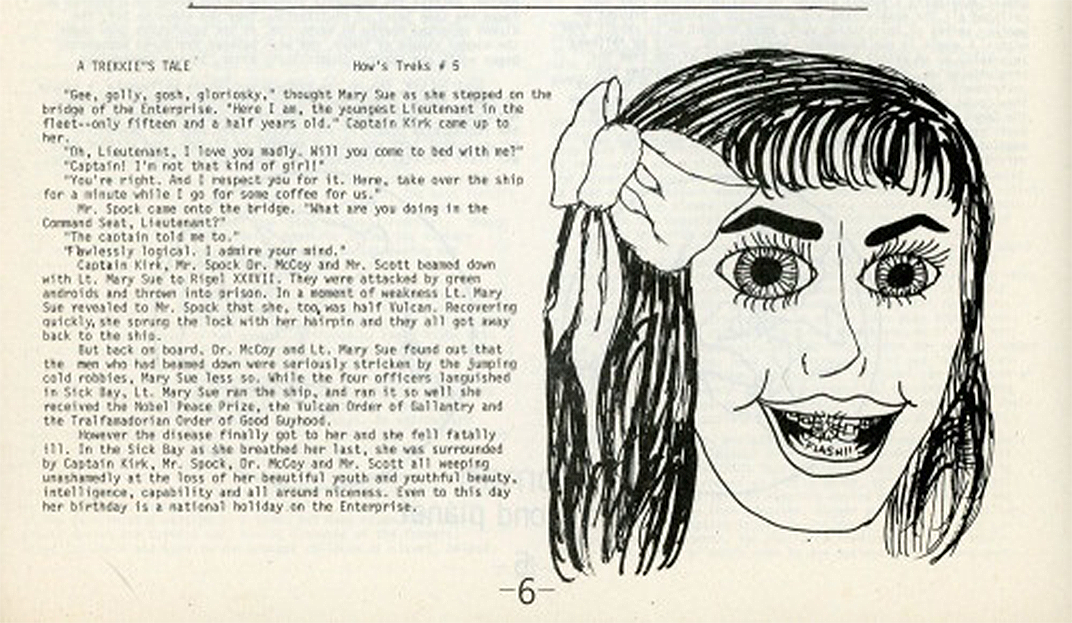

“Gee, golly, gosh, gloriosky," it began, written from the viewpoint of the youngest lieutenant ever in the history of the Federation, a 15-and-a-half-year-old, half-Vulcan named Mary Sue. Immediately upon coming aboard the USS Enterprise, Mary Sue catches the eye of the debonair Captain Kirk, who confesses his love to her and propositions a bedroom rendezvous. After she turns him down, scandalized— “Captain! I am not that kind of girl!”— Kirk immediately walks back the suggestion: "You're right, and I respect you for it,” he asserts, before tapping her to watch over the ship as he fetches them coffee.

Next, she encounters Mr. Spock, the Vulcan science officer, who asks why she’s sitting in the captain’s chair. Once she explains herself, Spock calls the decision “flawlessly logical.”

“A Trekkie’s Tale,” which Smith published anonymously in Menagerie #2, concludes after Mary Sue dies her heroic death; afterward, Smith writes, the entire crew weeps “unashamedly at the loss of her beautiful youth and youthful beauty, intelligence, capability and all-around niceness.” For good measure, the Enterprise turns her birthday into a national holiday on the ship.

“I wanted to write the complete sort of Mary Sue that there was because they were all alike,” says Smith. “It was just so typical that it just had to be done.”

While the original meaning of a Mary Sue referred to a stand-in character of any gender orientation, the reason Smith and Ferraro encountered more Mary Sues than Murray Sues when they were running Menagerie likely had more to do with who was writing in. Unlike the larger science fiction fanbase, which skewed male, both Smith and Ferraro remember that the “Star Trek” fandom they experienced was made up of mostly women. “Science fiction fandom, in general, was like 80 percent men,” Ferraro ballparks. “'Star Trek' fandom was the exact opposite; at least 75 percent women.”

Later, cultural critics began to make the argument that Mary Sues opened up a gateway for writers, particularly women and members of underrepresented communities, to see themselves in extraordinary characters. “People have said [the Mary Sue characters] actually seem to be a stage in writing for many people,” Smith says. “It's a way of exercising who they are and what they can imagine themselves doing.”

Naming the trope also allowed people to understand what they were doing when they set out to write a Mary Sue or Murray Sue character. “In terms of teaching writers a lesson, it was very useful in that people could say, well, that’s really a Mary Sue story. And then they could look at it and decide whether they wanted to change it,” says Ferraro.

While both Smith and Ferraro actively worked to popularize the term within the “Star Trek” fan community, neither expected it to catch on the way it has. “I was absolutely blown out of the water when I Googled it the first time and went, oh, my god,” says Ferraro. Smith agrees, “I am surprised that it held on so long. Many fan words get tossed around and they live for a while and then they die.”

But Mary Sue has withstood the test of time. Both articulate the surreal quality that comes with seeing a name they coined take on a life of its own. That includes the creeping sexism that's become associated with the term. "There were the people who would say anytime there was a female protagonist that’s a Mary Sue," Smith remembers. “It just developed in all sorts of ways."

But she’s found her peace with it. “You can’t control a term. Nobody does after a while,” she says. “It's like children. You raise them and you say, oh my gosh, what's happened here? And off they go, and you're pleased to get a call 40 years later from Smithsonian to talk about them.”