These Women Composers Should Be Household Names Like Bach or Mozart

Denied the same opportunities as their male counterparts, women like Lili Boulanger and Clara Schumann found ways to get their work in front of audiences

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/02/e0022480-e858-40fb-8f75-4964c45f8114/barbara_strozzi_web-resize.jpg)

What did it take to be a great classical composer? Genius was essential, of course. So too was a sustained education in composition. Usually, the great composer needed a professional position, whether court musician, conservatory professor, or Kapellmeister, and the authority, income and opportunities provided by that position. A great composer required access to the places where music is performed and circulated, whether cathedral, court, printers or opera house. And most, if not all, had wives, mistresses and muses, to support, stimulate and inspire their great achievements. There is, of course, a simpler answer: be born male.

The good news is that, although it might have been easier to achieve as a man, there are many painfully underappreciated female composers who were undoubtedly great. These forgotten women achieved artistic greatness despite the fact that for centuries the idea of genius has remained a male preserve; despite working in cultures which systematically denied almost all women access to advanced education in composition; despite not being able, by virtue of their sex, take up a professional position, control their own money, publish their own music, enter certain public spaces; and despite having their art reduced to simplistic formulas about male and female music — graceful girls, vigorous intellectual boys. Many of these women continued to compose, despite subscribing to their society’s beliefs as to what they were capable of as a woman, how they should live as a woman, and, crucially, what they could (and could not) compose as a woman. That’s often where their true courage lies.

Yes, women wrote music, they wrote it well, and they wrote it against the odds.

Take Francesca Caccini, whose opera La Liberazione di Ruggiero (the first written by a woman) so inspired the King of Poland that he rushed back to his home country from Florence, Italy, determined to create his own opera house — and invited Caccini to provide the first works for it.

What of Barbara Strozzi, who had more music in print in the 17th century than any other composer and was known and admired far beyond her native Venice?

Then there’s Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, acknowledged to be the first French composer of sonatas (avant-garde music in those days) and seen as the natural successor to Lully, who was the superstar of French music at the time.

And that only takes us up to 1700. Closer to our own time, things ironically became in some ways more difficult for women: the ideal of the “angel in the home” would be deadly to many a female composer’s professional, public career. A composer such as Fanny Hensel wrote one of the great string quartets of the 19th century and one of the great piano works of her era (Das Jahr) — along with over 400 other works — but due to her family’s views about a woman’s place, the vast majority of her works remained unpublished. The rest ended up in an archive, controlled by men who did not value (“She was nothing. She was just a wife”) and certainly did not share, what they had. Doesn’t make her any less great, though.

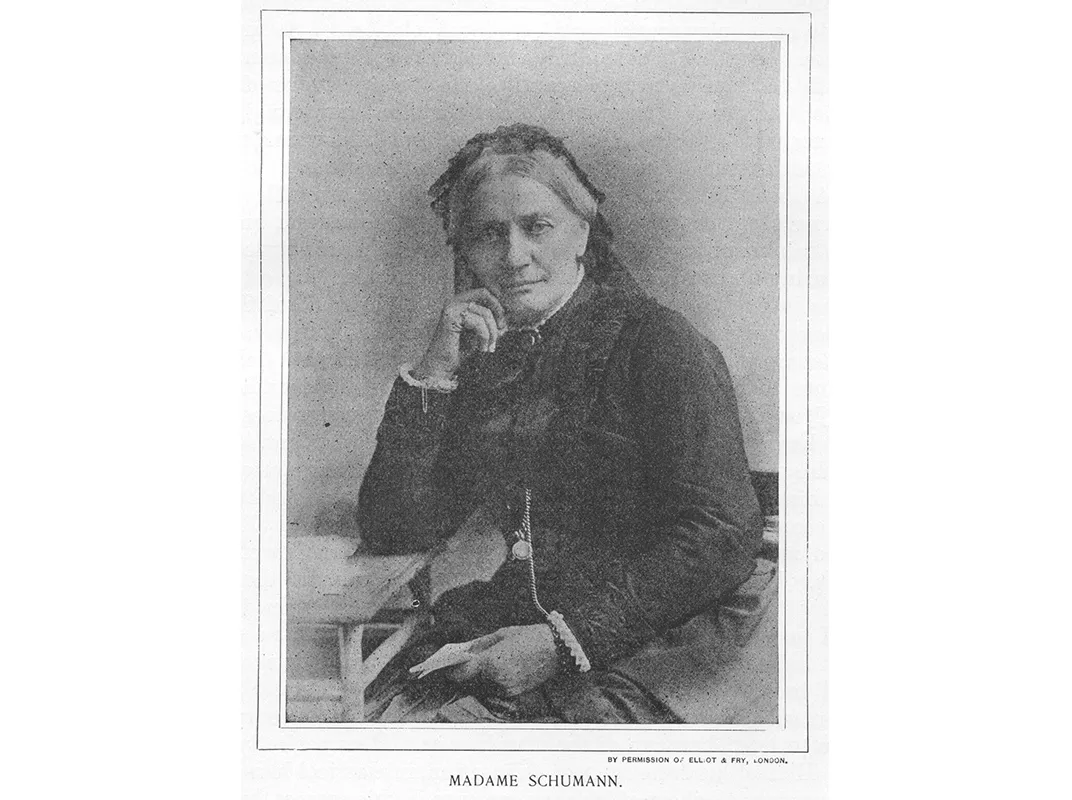

Clara Schumann, certainly one of the great pianists of the 19th-century, silenced herself as a composer for many reasons, none of them good. The usual interpretation is that she was overwhelmed by the demands of motherhood (Clara had eight children, seven of whom survived childhood), coupled with the need to support her seriously ill husband, Robert, himself a famed composer. However, she wrote some of her greatest works (her Piano Trio, for example) during acutely stressful times as a young wife and mother, and even when Robert was slowly dying in an asylum, Clara continued the most punishing of touring schedules, spending months on the road away from her family. It was Clara herself who, after Robert’s death, stopped composing, working tirelessly instead to promote her husband’s work and creating the (male) canon that would, ironically, exclude her. The music she did write is good, sometimes great: what she was capable of we will never know.

Nor will we know what turn-of-the-20th-century composer Lili Boulanger, dead at 24, would have created she had not been felled by what we now know to be Crohn’s Disease. Seriously ill from her teens, Boulanger nevertheless was the first woman to win the prestigious Prix de Rome in her native Paris, and spent her final years composing furiously against the clock: powerful, haunting (great?) works that leave the listener struck with their beauty and, some would say, faith.

What about the prolific Elizabeth Maconchy, who has been described as Britain’s “finest lost composer”? Her luscious work, The Land, was performed at the 1930 Proms to international acclaim (“Girl Composer Triumphs” screamed the headlines — she was 23), and she would compose a series of string quartets that have been compared to those of Shostakovich. Like Boulanger, Maconchy faced an early death. Just two years after her Proms triumph, Maconchy contracted tuberculosis and was told she stood no chance against the disease – unless she moved to Switzerland, and even then the odds weren’t good. Maconchy’s response? She wanted to die in her English homeland. Maconchy and her new husband, William LeFanu, moved to a village in Kent, where they resolutely, some would say naively, set up home in a three-sided wooden hut complete with piano, always open to the elements, providing an extreme version of the “fresh-air cure” of the time. William nursed his wife assiduously through some terrible times. Whether it was the three-sided hut, the care of her husband, or the composer’s sheer willpower, Elizabeth Maconchy did not die. In fact, she lived until 1994, continuing to compose into old age.

Maconchy, for one, did everything that her American predecessor, Amy Beach, suggested needed to be done to create a world in which the public would “regard writers of music” and estimate “the actual value of their works without reference to their nativity, their color, or their sex.” Get your work out there, advised Beach in Etude magazine in 1898: compose “solid practical work that can be printed, played, or sung.” Maconchy herself wanted to be called “a composer,” insisting on the absurdity of the term “woman composer” and reminding us, if we need reminding, that if you listen to an unknown piece of music, it is impossible to tell the sex of its creator. Have we reached Beach’s utopia? I think not.

What is striking about these women, is that each worked so hard not only to have the chance to compose, but to get her music out into the (traditionally male-dominated) public world. Barbara Strozzi, denied access to Venetian opera - let alone a job at St Mark’s - because of her sex, made sure that she reached audiences throughout Europe by using the new media, print. Fanny Hensel, denied the professional, international opportunities seized by her brother, Felix Mendelssohn, created a special musical salon in Berlin. Lili Boulanger, after watching and learning from the failure of her older sister, Nadia, to break through the Parisian glass ceiling on talent alone, smashed through it herself by presenting herself in public at least as a fragile child-woman. And, for the future, we need to create spaces in which we can hear women’s music, not simply because they are women, but so that we can decide for ourselves whether they are “great.” We might even, perhaps, be enriched by their — whisper it — genius.