This Hollywood Titan Foresaw the Horrors of Nazi Germany

Carl Laemmle, the founder of Universal Pictures, wrote hundreds of affidavits to help refugees escape Europe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/e5/e4e59ed1-b388-4aa3-97eb-986e3422a0e0/carl_laemmle_in_1918.jpg)

On October 6, 1938, one of the most influential men in Hollywood sat down to type an urgent letter to his relative, film director William Wyler.

“Dear Mr. Wyler:” the 71-year-old began. “I want to ask you a very big favor.”

Carl Laemmle’s name may have faded some from the annals of Hollywood history, but “Uncle Carl,” as most called him, who was born 150 years ago, was one of the early titans of Classic Hollywood.

The founder and first president of Universal Pictures, Laemmle “looked like an avuncular elf,” Neal Gabler wrote in his canonical history An Empire of Their Own: “[F]ive feet two inches tall, a constant gap-toothed smile, merry little eyes, a widening expanse of pate, and a slight paunch that was evidence of the beer and the food he enjoyed.”

His constant smile had never been under more strain, though, than when he wrote the desperate letter to Wyler, imploring him to write affidavits for Jews and Gentiles alike who needed them to get out of Nazi Germany.

“I predict right now that thousands of German and Austrian Jews will be forced to commit suicide if they cannot get affidavits to come to America or to some other foreign country,” Laemmle wrote.

In less than a year, Germany would invade Poland, officially starting World War II. But before September 1939, Nazi Germany’s acts of terrorism and suppression toward those who did not fit the Aryan ideal (a situation magnified after Germany annexed Austria and the Sudetenland in 1938) had already launched a refugee crisis.

Laemmle’s career trafficked in horror. Under his watch, Universal produced some of history's most iconic monster movies, including Dracula, The Mummy, and Frankenstein. But on the cusp of World War II, nothing felt as frightening as the reality Laemmle was watching unfold. So, in the final years of his life, he pledged to personally try to help more than 200 people escape Hitler’s grasp before it was too late.

By happenstance, Laemmle’s own life gave him a front-seat view of the tragedy unfolding in Europe. Fifty-four years earlier, Karl Lämmle was one of many German Jews who immigrated to the United States. Given a ticket for the S.S. Neckar for his 17th birthday by his father, Laemmle made the trip across the Atlantic, leaving behind his family and hometown of Laupheim, a village in Wurttemberg, Germany so small that it could have fit on the future Universal Pictures studio lot.

Laemmle didn’t speak English when he arrived in New York on February 14, 1884, with $50 in his pocket, but he eventually saved up enough money to go into business for himself. As the story goes, he originally planned to open five- and ten-cent stores, but when he saw crowds pouring into a storefront nickelodeon, he decided to enter the burgeoning film business instead. At age 39, he opened White Front, the first of what would be a series of nickelodeons. Soon he formed the Independent Motion Picture Company, and then came Universal Pictures.

He founded his giant studio, a piecemeal of existing film companies, in the San Fernando Valley, and began cranking out cheap action pictures. World War I had already started when Universal Studios opened its doors in 1915, and Laemmle took his adopted homeland’s side in the propaganda war being waged against Germany. He helped produce multiple films that portrayed his native country as brutal and barbaric, none more damaging than 1918’s The Kaiser, The Beast of Berlin.

After the war’s end, Laemmle made efforts to make amends with his homeland. Not only did he draw attention to and money for humanitarian efforts in Germany, but he also traveled there annually and supported many townspeople in Laupheim. As David B. Green put it in Haaretz, “[H]e invested great efforts (and cash) in cultivating an image of himself as a rich uncle dedicated to the Laupheim’s improvement.”

Laemmle even opened a German branch of Universal in the 1920s, cementing his studio’s interests in the German market. Incidentally, it was the German talent Laemmle hired for Universal that helped give rise to the studio’s signature monster movie. Thomas Schatz notes in The Genius of the System Laemmle’s export hires were steeped not just in "European tradition of gothic horror, but also in the German Expressionist cinema of the late teens and early 1920s.” A host of horror flicks followed, starting with 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Around this time, Laemmle had every reason to see himself as a favored son of Laupheim. Local politicians even made him an honorary citizen (he had been forced to give up his citizenship when he first immigrated to the U.S.).

Then German author Erich Maria Remarque published his anti-war novel, All Quiet on the Western Front. The book debuted on January 31, 1929, and sold 2.5 million copies in 22 languages in its first 18 months in print. That July, Laemmle and his son, Julius, traveled to Germany to procure screen rights to the novel.

Remarque was reluctant to have the book adapted as a motion picture, but finally agreed to sign over the rights on one condition—that the film interpret the story without any significant additions or alterations.

Julius, known as Junior, was put in charge of the picture. The young Laemmle had just turned 21, and had visions of reshaping Universal into a studio that produced high-quality features. He also had something to prove—his first movie as a producer, an adaptation of the play Broadway, had taken heavy criticism for wandering too far away from the initial material. With that in mind, he too was committed to staying true to the original story.

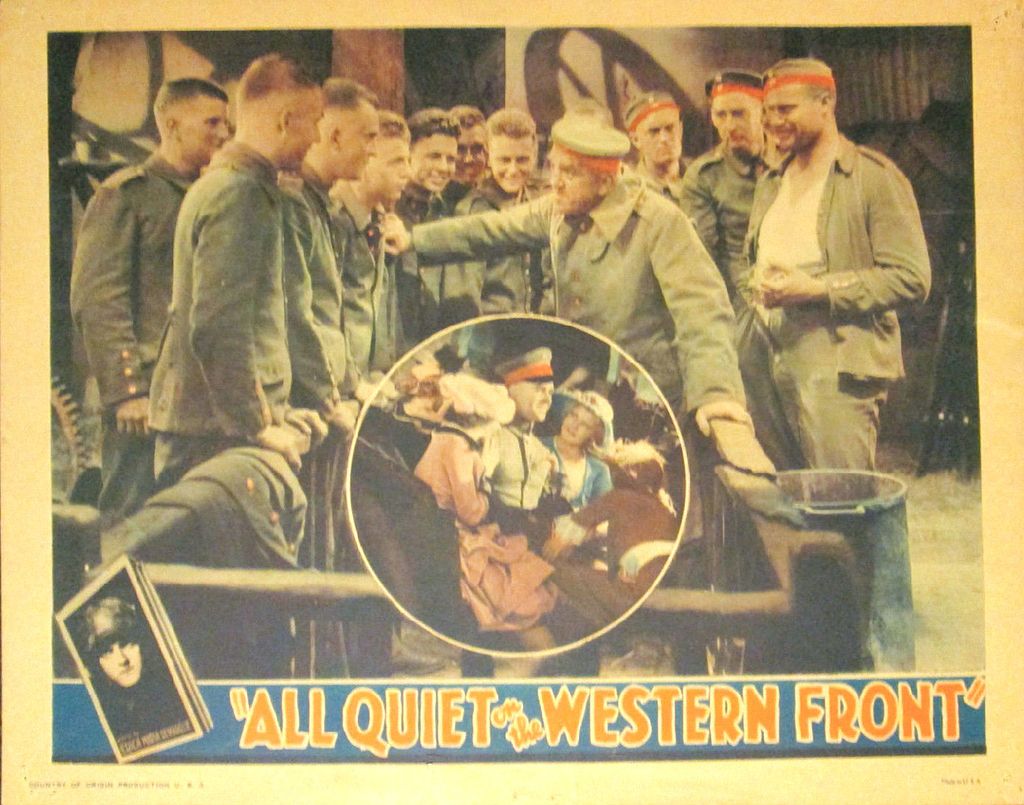

Universal released the film in 1930, bringing Remarque’s story about German volunteer soldiers stationed on the front lines at the bitter end of World War I to life. The film was met with praise in the U.S., with Variety writing, “Here exhibited is a war as it is, butchery.”

It debuted with similarly positive feedback in England and France. But then it premiered in Germany. What followed offered a window into the political situation that had already taken root. That September’s elections, held only a few months before the movie’s opening, highlighted the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party three years before Hitler became chancellor. The Nazis accrued 18 percent of the vote, bringing the number of the party's seats in the Reichstag up from 12 to 107 seats. Now, the Nazis had control of the second most powerful party in Germany.

Laemmle saw All Quiet as a way to make amends with Germany. He believed the film stayed true to the horrors of World War I, but also showed the German people in a good light. What he didn’t yet realize was that a movie that showed German defeat could only be viewed as anti-German by the country's new far right.

On December 4, the movie quietly debuted in Germany. The next day, Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels led the charge against what he called "a Jewish film," the go-to defamation for anything the Nazis disapproved of. Soon there were Nazi street mobs demonstrating against All Quiet on the Western Front. Crowds also protested in front of theaters, and even inside them, terrorizing audiences by releasing snakes, mice and stink bombs.

“All at once the Nazis had caused an uproar that, in years later, could be viewed as just the beginning of the violence,” wrote Bob Herzberg in The Third Reich on Screen. “In Germany, the attacks had hit only the nation’s Jews; now, thanks to a film that was an international hit, the Nazis’ violence was on full display for all the world to see.”

The movie was brought before the Reichstag for a debate about whether or not it should continue to be screened in Germany. The loudest voice of calling for its removal: Adolf Hitler. Soon after, the Supreme Board of Censors in Germany reversed its decision to allow the movie to screen in Germany. The explanation given for the new ban was that the movie was "endangering Germany's reputation.”

Laemmle was beside himself. “The real heart and soul of Germany has never been shown to the world in all its fineness and honor as it is shown in this picture,” he wrote in a paid advertisement that ran in German papers.

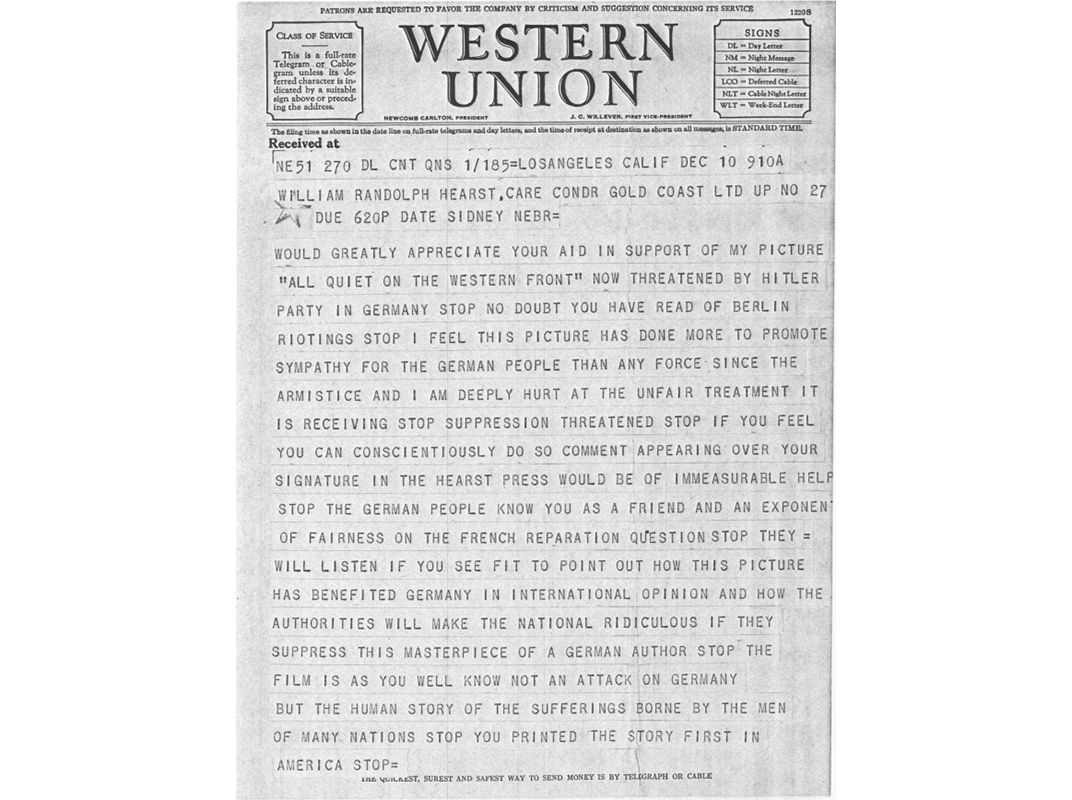

Laemmle believed so strongly in the anti-war picture’s ability to promote peace that he did all he could to pressure Germany to continue to screen the film. According to author Andrew Kelly, he even tried to make a case for why the movie deserved the Nobel Peace Prize. Pleading with the most influential newspaper man in the United States, William Hearst, who he knew had the ear of German audiences, he asked for any help to persuade Germans to leave All Quiet in theaters.

The day after the ban, Hearst printed an editorial on the front page of all of his newspapers in defense of the movie as a “pacifist film,” Ben Urwand writes in The Collaboration. But it made no difference. As the Nazi daily Völkischer Beobachter reminded its readers in a piece titled "The Beast of Berlin,” in the eyes of an increasing number of Germans, Laemmle was the same "film Jew" responsible for the anti-Kaiser piece, writes Rolf Giesen in Nazi Propaganda Films: A History and Filmography.

All Quiet eventually returned to German screens. In June 1931, Laemmle resubmitted the film to the censors, this time offering a version with heavy edits that softened some of the film's darker meditations on the pointlessness of war. The Foreign Office, ever mindful of Germans living abroad, agreed to resume screenings in Germany, if Universal agreed to send this sanitized version out for all foreign distribution. One of the deleted segments, Urwand writes, included the line, "It is dirty and painful to die for the Fatherland."

Even that defanged version wouldn’t last in Germany long. In 1933, the film was banned for good. So was Laemmle, who was issued an interdiction against entering the country because of his Jewish background and American connections.

Considering what transpired with All Quiet, Laemmle was fearful of what was still to come in Germany. He recorded his fears in another letter to Hearst dated January 28, 1932, appealing to him, again, as “the foremost publisher in the United States” to take action against Hitler.

“I might be wrong, and I pray to God that I am, but I am almost certain that Hitler’s rise to power, because of his obvious militant attitude toward the Jews, would be the signal for a general physical onslaught on many thousands of defenseless Jewish men, women and children in Germany, and possibly in Central Europe as well, unless something is done soon to definitely establish Hitler’s personal responsibility in the eyes of the outside world,” Laemmle wrote. He ended the note with a call to arms. “A protest from you would bring an echo from all corners of the civilized world, such as Mr. Hitler could not possibly fail to recognize.”

But it would take until the horror of Kristallnacht in 1938 for Hearst, who had misjudged the danger of the Nazis and given them sympathetic coverage during the 1930s, to turn the full engine of his press against the Third Reich. Laemmle, meanwhile, sold his own interest in Universal Pictures Corporation in April 1936 and retired from business in order to do everything in his power to help relatives and friends stuck in Germany.

When it came to German Jews seeking asylum, the immigration process was fraught with obstacles. As explained by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, applicants not only had to make it through the exclusionary quota system, limiting the number of immigrants from each country, but they also needed affidavits from American sponsors who would vouch for their character and pledge financial support.

Affidavits, then, were Laemmle's best chance to help Jewish refugees. He became a prolific affidavit writer, so much so that he told Wyler in his 1938 letter, “I have issued so many personal affidavits that the United States government won’t accept any more from me excepting for my closest blood-relatives."

Laemmle was frustrated when his attempts hit administrative roadblocks. In one letter dated November 22, 1937 to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, he expressed concerns over the German Consul's apparent objections to his work on behalf of refugees. “What I would like to know from you is this:” Laemmle wrote Hull. “What further assurances can I give your Consul General that I am honest, sincere, able and willing to carry out every promise and guarantee I make in the affidavits? Any assistance or advice that you may be able to give me, will be very much appreciated.”

As Laemmle wrote and wrote, affidavits piled up. Over the course of 15 years, he wrote to the German consul that he penned at least 200 of them. He continued to seek Hull's help, too. On April 12, 1938, he asked Hull if the Consul General in Stuttgart could do more. “In my opinion he has made it unnecessarily hard in practically each and every instance where I issued an affidavit, for the applicant to receive his visa," he wrote. "It has been a heart-breaking effort on my part to have him pass favorably on my affidavits. A year or two ago, it was so much easier than it is now.”

Laemmle complained that the consul was more reluctant to accept his affidavits because of his advanced age. But he told Hull that even if he died, his family would back up his word financially. His work was too important to stop. “I feel it is the solemn duty of every Jew in America who can afford to do it to go the very limit for these poor unfortunates in Germany,” he wrote.

Even as the plight of Jews worsened, Laemmle kept trying to help them, often beseeching other public figures on their behalf. In the summer of 1939, he telegraphed President Franklin Delano Roosevelt about the plight of a group of Jewish refugees who had fled on ships to Havana, Cuba, but weren’t allowed to disembark. “YOUR VOICE IS THE ONLY ONE THAT HAS THAT NECESSARY CONVINCING POWER IN A CASE LIKE THIS, AND I BESEECH YOU TO USE IT IN THIS GREAT HUMAN EXTREMITY,” he wrote.

Laemmle died a few months later on September 24, 1939—just after the start of World War II. While his legacy in film has far outlasted him, Laemmle’s fight to save lives has only resurfaced in popular culture in recent years. That recognition is in large part thanks to the late German film historian Udo Bayer, who had made it his life mission to publicize Laemmle’s humanitarian work, and wrote the bulk of information available about Laemmle’s work with refugees.

But a key piece of Laemmle’s story remains buried in the National Archives—the affidavits he wrote. In a 1998 essay called "Laemmle’s List,” Bayer noted that in 1994, a woman named Karin Schick unearthed 45 documents in the Archives, which detailed documents concerning Laemmle's correspondence with American officials from November 1936 until May 1939. However, at the time, Bayer wrote, “the actual files were not available, only index cards with date and names of the persons concerned.”

But today, the National Archives cannot confirm it has those documents at all. “You are one of many people who have referenced this unfortunately-sourced article and asked about the documents on that list," a National Archives librarian wrote in response to an email inquiry about the files. "While Mr. Bayer provides a list of documents that purport to deal with Carl Laemmle’s affidavit activities, he provides no file numbers that will lead one to those documents.”

To identify the existing documentation would require going through all 830 boxes of files in the series. Additionally, not all documentation relating to visa applications has been preserved in the National Archives.

But the information that is available speaks volumes on Laemmle’s commitment. In honor of his 150th birthday, Germany’s Haus der Geschichte Baden-Württemberg in Stuttgart is currently hosting, “Carl Laemmle presents,” which highlights his impact on the early film industry.

The exhibit includes the 1938 letter Laemmle wrote to Hull. On loan from the National Archives, it captures the sentiment that drove Laemmle onward. "I have never in all my life been so sympathetic to any cause as I am to these poor innocent people who are suffering untold agony without having done any wrong whatsoever," he wrote, just months before Kristallnacht.