This Man Made the First Canned Cranberry Sauce

How Marcus Urann’s idea revolutionized the cranberry industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/cf/7dcf848a-8e98-4061-ba83-4c6f6e78162d/istock-655381506.jpg)

Americans consume 5,062,500 gallons of jellied cranberry sauce—Ocean Spray’s official name for the traditional Thanksgiving side dish we know and love that holds the shape of the can it comes in—every holiday season. That’s four million pounds of cranberries—200 berries in each can—that reach a gel-like consistency from pectin, a natural setting agent found in the food. If you’re part of the 26 percent of Americans who make homemade sauce during the holidays, consider that only about five percent of America’s total cranberry crop is sold as fresh fruit. Also consider that 100 years ago, cranberries were only available fresh for a mere two months out of the year (they are usually harvested mid-September until around mid-November in North America making them the perfect Thanksgiving side). In 1912, one savvy businessman devised a way to change the cranberry industry forever.

Marcus L. Urann was a lawyer with big plans. At the turn of the 20th century, he left his legal career to buy a cranberry bog. “I felt I could do something for New England. You know, everything in life is what you do for others,” Urann said in an interview published in the Spokane Daily Chronicle in 1959, decades after his inspired career change. His altruistic motives aside, Urann was a savvy businessman who knew how to work a market. After he set up cooking facilities at as packinghouse in Hanson, Massachusetts, he began to consider ways to extend the short selling season of the berries. Canning them, in particular, he knew would make the berry a year-round product.

“Cranberries are picked during a six-week period,” Robert Cox, coauthor of Massachusetts Cranberry Culture: A History from Bog to Table says. “Before canning technology, the product had to be consumed immediately and the rest of the year there was almost no market. Urann’s canned cranberry sauce and juice are revolutionary innovations because they produced a product with a shelf life of months and months instead of just days.”

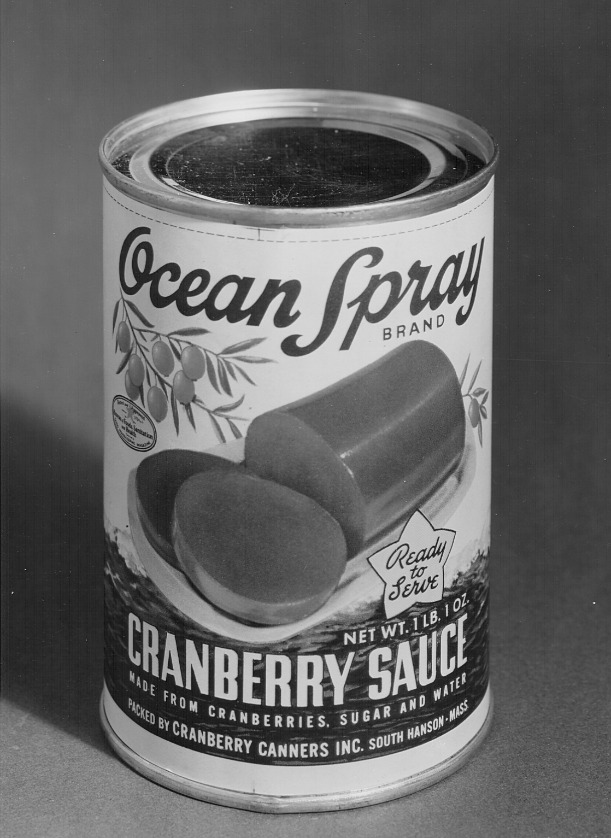

The jellied cranberry sauce “log” became available nationwide in 1941. Image courtesy of Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc.

Native Americans were the first to cultivate the cranberry in North America, but the berries weren’t marketed and sold commercially until the middle of the 18th century. Revolutionary war veteran Henry Hall is often credited with planting the first-known commercial cranberry bed in Dennis, Massachusetts in 1816, but Cox says Sir Joseph Banks, one of the most important figures of his time in British science, was harvesting cranberries in Britain a decade earlier from seeds that were sent over from the states—Banks just never marketed them. By the mid-19th century, what we know as the modern cranberry industry was in full swing and the competition among bog growers was fierce.

The business model worked on a small scale at first: families and members of the community harvested wild cranberries and then sold them locally or to a middle man before retail. As the market expanded to larger cities like Boston, Providence and New York, growers relied on cheap labor from migrant workers. Farmers competed to unload their surpluses fast—what was once a small, local venture, became a boom or bust business.

What kept the cranberry market from really exploding was a combination of geography and economics. The berries require a very particular environment for a successful crop, and are localized to areas like Massachusetts and Wisconsin. Last year, I investigated where various items on the Thanksgiving menu were grown: “Cranberries are picky when it comes to growing conditions… Because they are traditionally grown in natural wetlands, they need a lot of water. During the long, cold winter months, they also require a period of dormancy which rules out any southern region of the U.S. as an option for cranberry farming.”

Urann’s idea to can and juice cranberries in 1912 created a market that cranberry growers had never seen before. But his business sense went even further.

“He had the savvy, the finances, the connections and the innovative spirit to make change happen. He wasn’t the only one to cook cranberry sauce, he wasn’t the only one to develop new products, but he was the first to come up with the idea,” says Cox. His innovative ideas were helped by a change in how cranberries were harvested.

In the 1930s, techniques transitioned from “dry” to “wet”— a confusing distinction, says Sharon Newcomb, brand communication specialist with Ocean Spray. Cranberries grow on vines and can be harvested either by picking them individually by hand (dry) or by flooding the bog at time of harvest (wet) like what we see in many Ocean Spray commercials. Today about 90 percent of cranberries are picked using wet harvesting techniques. “Cranberries are a hearty plant, they grow in acidic, sandy soil,” Newcomb says. “A lot of people, when they see our commercials think cranberries grow in water.”

The water helps to separate the berry from the vine and small air pockets in the berries allow them to float to the surface. Rather than taking a week, you could do it in an afternoon. Instead of a team of 20 or 30, bogs now have a team of four or five. After the wet harvesting option was introduced in the mid to late 1900s, growers looked to new methods of using their crop, including canning, freezing, drying, juicing berries, Cox says.

Urann also helped develop a number of novel cranberry products, like the cranberry juice cocktail in 1933, for example, and six years later, he came up with a syrup for mixed drinks. The famous (or infamous) cranberry sauce “log” we know today became available nationwide in 1941.

Urann had tackled the challenge of harvesting a crop prone to glut and seesawing prices, but federal regulations stood in the way of him cornering the market. He had seen other industries fall under scrutiny for violating antitrust laws; in 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, which was followed by additional legislation, including the Clayton Act of 1914 and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914.

In 1930, Urann convinced his competitors John C. Makepeace of the AD Makepeace company—the nation’s largest grower at the time—and Elizabeth F. Lee of the New Jersey-based Cranberry Products Company to join forces under the cooperative, Cranberry Canners, Inc. His creation, a cooperative that minimized the risks from the crop’s price and volume instability, would have been illegal had attorney John Quarles not found an exemption for agricultural cooperatives in the Capper-Volstead act of 1922, which gave “associations” making agricultural products limited exemptions from anti-trust laws.

After World War II, in 1946, the cooperative became the National Cranberry Association and by 1957 changed its name to Ocean Spray. (Fun Fact: Urann at first “borrowed” the Ocean Spray name and added the image of the breaking wave, and cranberry vines from a fish company in Washington State from which he later bought the rights). Later, Urann would tell the Associated Press why he believed the cooperative structure worked: ”grower control (which) means ‘self control’ to maintain the lowest possible price to consumers.” In theory, the cooperative would keep the competition among growers at bay. Cox explains:

From the beginning, the relationship between the three was fraught with mistrust, but on the principle that one should keep one’s enemies closer than one’s friends, the cooperative pursued a canned version of the ACE’s fresh strategy, rationalizing production, distribution, quality control, marketing and pricing.

Ocean Spray still is a cooperative of 600 independent growers across the United States that work together to set prices and standards.

Marcus L. Urann was the first bog owner to can cranberries in 1912. Image courtesy of Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc.

We can’t thank Urann in person for his contribution to our yearly cranberry intake (he died in 1963), but we can at least visualize this: If you lay out all the cans of sauce consumed in a year from end to end, it would stretch 3,385 miles—the length of 67,500 football fields. To those of you ready to crack open your can of jellied cranberry sauce this fall, cheers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)