This $1.4 Million “Bird” Makes an African-American Art Collection Soar to New Heights

With his first major contemporary acquisition, the Detroit Institute of Arts’ new director is reinvigorating the museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/bd/d4bdc93a-c24b-4e92-94b7-5156faf2819b/bird-david-hammons.jpg)

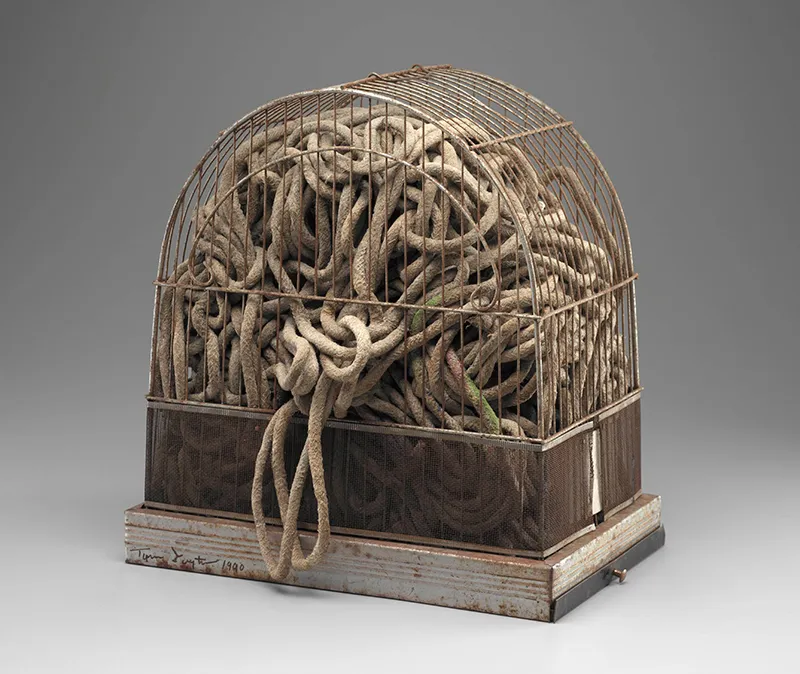

Festooned with feathers and entangled in chicken wire, the basketball dangles perilously in the frame of a white-painted Victorian birdcage and, as you walk around it, projects a sort of stifled frenzy. There’s a feeling of movement in the wired frizziness, yet the ball is trapped in its confounded suspension. These objects—detritus scavenged from the streets of New York City—comprise “Bird,” a 1990 sculpture by David Hammons, a willfully inaccessible African-American artist-provocateur. Both a wicked pastiche and a joyful celebration of its physical material, “Bird” is a work of poetic subversion. “Historically, the African-American community has been given opportunities in sports and music and has excelled in those arenas, but it has also been denied opportunities and is still caged,” observes Salvador Salort-Pons, who last year became director of the Detroit Institute of Arts. As part of a campaign to participate in the city's revitalization and turn this lofty mountain of elite art into a street-level people's museum, he made "Bird" his first major contemporary acquisition.

The DIA plans to exhibit the work this month in its African-American art gallery—the start of a full-court press, if you will, to broaden the appeal of the institute and deepen its commitment to African-American art. At $1.4 million, "Bird" is one of the priciest works of contemporary art purchased by the under-endowed museum in two decades and heralds a new chapter for a cultural gem recently yanked out of city control and transferred to a charitable trust. Though the DIA houses a 600-piece African-American collection—sizable for a museum of its caliber—it’s been criticized lately by local activists for neglecting black artists in a city that’s 80 percent black. “Our goal is to be relevant to all our visitors,” says Salort-Pons. “We want to engage everyone who comes here.” The young, charismatic Spaniard wants to reinvigorate the venerable DIA—whose centerpiece is Diego Rivera's populist "Detroit Industry" murals—by forging a town square around it and other midtown institutions.

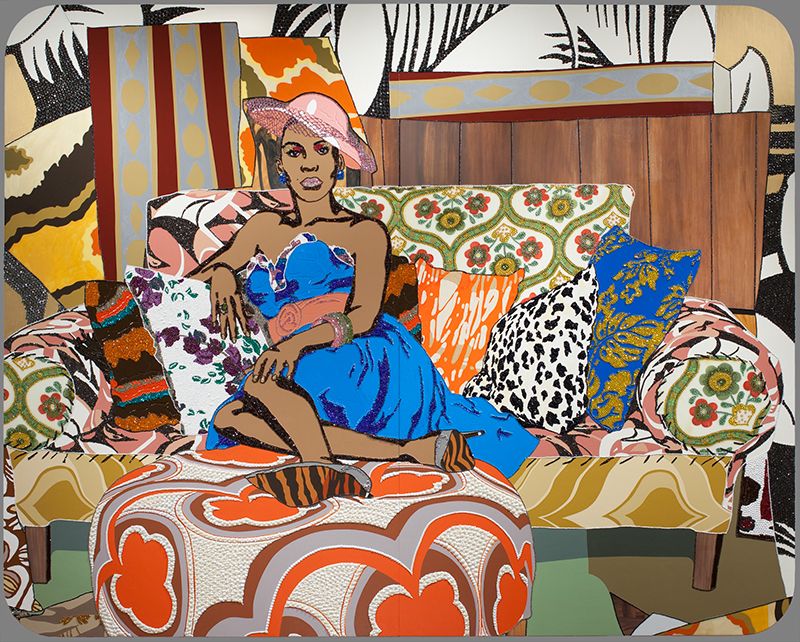

With the market for African-American art now so hot it’s practically molten, Salort-Pons is trying to get in on the action before he’s priced out. His wish list includes painter Mark Bradford, painter-sculptor Kerry James Marshall and Harlem Renaissance pioneer Aaron Douglas. Having a Hammons, who made his name selling snowballs in Greenwich Village and bewigging a boulder with hair swept from the floor of a Harlem barber shop, is as essential to a comprehensive African-American collection as a da Vinci or a Rembrandt would be to a European one, says Salort-Pons. The work of the 73-year-old Hammons has metaphoric if not talismanic powers says Lex Braes, a Pratt Institute professor who has long followed the artist’s career. “He’s a visual poet, wild, inventive with great authority in restraint. He reveals what lies beneath the charades of American life and brings dignity to the commonplace.”