Time After Time

William Christenberry embraces the impermanent

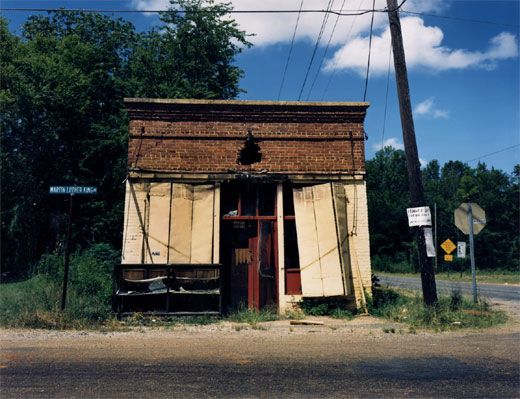

For years, William Christenberry saw the Bar-B-Q Inn only with its windows shuttered. When he finally came upon it with its doors open and went inside, he found a bartender who was affable but somewhat bemused that the skinny, clean-cut stranger would be interested in an old juke joint. Yet Christenberry kept going back, for more than 20 years.

"I was in love with the proportions of the building," he says in his muted Alabama drawl. Beyond that, there was "its meaning in that neighborhood" come nightfall—"as a wonderful gathering place where people came and relaxed, shot the breeze, listened to music." One day in 1971, Christenberry stood in the middle of the road and snapped pictures with his Brownie camera, pausing only to dodge the occasional car. Over the years, he traced the mark of time on the Bar-B-Q Inn (eventually trading his Brownie for a large-format camera) until, in 1991, only a concrete slab remained.

"Just like that, I lost one of my favorite subjects," he says.

An open-air carwash now sits on the site, in Greensboro, Alabama, but there are still plenty of what his mother once affectionately called "those rusted, worn-out, bullet-ridden places" in surrounding Hale County. Christenberry, now 70, spent the summers of his youth there, fishing and picking cotton on his grandparents' farms. As an adult—after he had moved away to pursue a career as an artist—he began to see in those places something beyond nostalgia.

"There's a sense of loss, of coming to a place you've been visiting for years and realizing that something you took as permanent isn't," says Eleanor Harvey, chief curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, home to "Passing Time: The Art of William Christenberry," which runs through July and coincides with the release of a new catalog of his multimedia work.

Christenberry initially shot his Hale County photographs as color references for paintings, but they became artworks unto themselves, in his mind and in others'. "His images fit at an interesting crossroads between photography as a kind of documentary tool and photography as a high, metaphorical art form," says Harvey. Color photography, she notes, was not highly regarded when he started making his Brownie prints, but his work inspired such peers as William Eggleston—who shot in black and white until he met Christenberry in the early 1960s—to push the medium further.

Christenberry was born in Tuscaloosa in 1936, the same year that Walker Evans and James Agee came to Hale County to take photographs and interview residents for what would become Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, their classic study of Depression-era sharecroppers. Christenberry had already trained as an Abstract Expressionist painter when he chanced upon a reprint of the book in a Birmingham store in 1960.

"I flipped through it and said, 'My goodness, I know some of these people,'" he recalls. The vision expressed in the book—through both Evans' images and Agee's mix of poetry, prose and journalism—inspired Christenberry to take a fresh look at the architecture and artifacts of his youth. "It just seemed to me, then and now, quite a discovery" of deep meaning in a familiar landscape, he says.

In 1961, Christenberry left Alabama for New York City, where he went through six jobs in a year—including stints as a church janitor and an art gallery gopher, and a single day as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art—before finally working up the nerve to contact Evans. Then an editor at Fortune, Evans invited him in for a chat, got him a job in the Time-Life photo library and eventually became a friend and mentor. In 1968, Christenberry moved to Washington, D.C., where he teaches drawing and painting at the Corcoran College of Art and Design. But he returns to Hale County for several weeks every summer to visit family members, take pictures and recharge his batteries. The Deep South's cemeteries, gourd trees, road signs and weatherbeaten buildings have remained the focus of his work.

"Being away from it gives me a perspective I wouldn't have otherwise," Christenberry says in the bright, loft-like studio behind his house, which is decorated with his paintings, sculptures and a large wall of signs that he has "appropriated" over the years, including ads for Grapette Soda and Tops Snuff. "I've taken pictures of other things, but they're very pedestrian....They don't resonate for me with the same feeling that I experience when I'm looking at my subjects in my territory."

Lately, however, the artist has become unsure of what he'll find when he goes home to Alabama. "Sadly, for me, a lot of the true vernacular architecture is rapidly disappearing," he says. "What you often see, much to my disdain, is a mobile home—a flat-roof, aluminum-sided building—move in. And it'll have to be a whole other generation of artists that, in time, might be interested in those."

Carolyn Kleiner Butler, a journalist in Washington, D.C., wrote on Ernest Withers for "Indelible Images" in April 2005.