In June 2016, then-Secretary of Defense Ash Carter announced that the United States would be lifting a ban on transgender people serving openly in the armed forces. “We’re talking about talented Americans who are serving with distinction or who want the opportunity to serve,” Carter said at the time. “We can’t allow barriers unrelated to a person’s qualifications to prevent us from recruiting and retaining those who can best accomplish the mission.”

The next summer, President Donald Trump tweeted his intention to maintain the ban. In particular, he raised concerns about the medical costs involved in gender transitions. In March 2018, the executive branch barred transgender people from enlisting. The courts initially blocked the orders, but an appeals court reversed that decision. The Supreme Court ruled on January 22 that Trump’s restrictions could go into effect while the matter is making its way up through the legal system.*

It’s hard to know exactly how many transgender individuals are serving in the armed forces today. In a 2016 study, undertaken at the request of the Defense Department, the RAND Corporation put the number between 2,150 and 10,790. (These estimates were based on surveys of the general population.)

The study’s lead author, Agnes Gereben Schaefer, says only a small fraction of transgender people are likely to seek hormone treatment or surgery. “We estimated that between 30 and 140 active personnel would seek hormone treatment a year,” Schaefer says. “And between 25 to 100 would seek surgical treatment. That would cost between $2.4 million and $8.4 million a year. In terms of the Defense Department’s $6 billion budget, we’re talking about 0.04% to 0.1%.”

Readiness was another question the RAND study investigated. The researchers examined four of the 18 countries where transgender individuals are allowed to serve openly: Australia, Canada, Israel and the United Kingdom. “The big takeaway is there hasn’t been a significant impact on unit cohesion or operational readiness,” Schaefer says.

The proposed ban would not only prevent current personnel from transitioning; it would apply to anyone experiencing “gender dysphoria”—a feeling of distress at living in the wrong gender. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) does not advise psychiatrists to help trans people live with the gender they were assigned at birth. On the contrary, it suggests helping them transition to the gender in which they feel at home. But the new ban would bar trans people from enlisting unless they’ve “been stable for 36 consecutive months in their biological sex”—in other words, unless they’re willing to say they aren’t transgender after all.

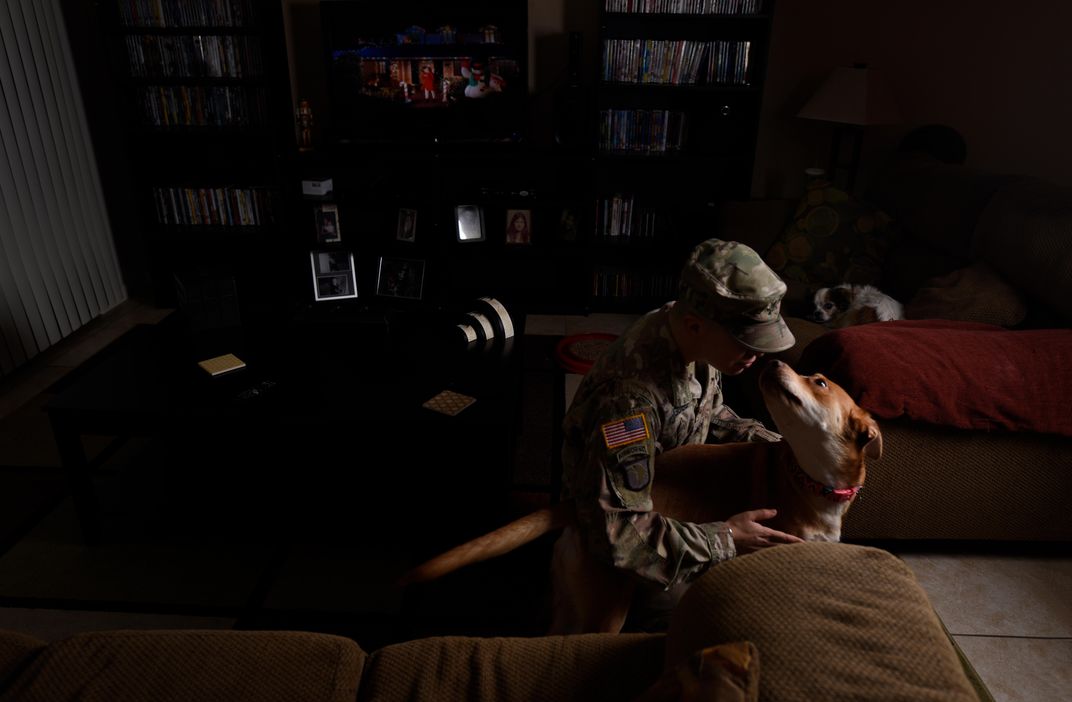

With the fate of the ban still uncertain, we sent our photographer to meet five openly transgender members of the U.S. military. All but one of them told us they had full support from their superiors and other members of their units during their transitions. It’s unclear how typical their experiences were. In a survey included in this issue, only 39 percent of military personnel said they supported transgender people serving openly. But the people featured in this story said they were able to build on existing relationships to earn acceptance. “The younger men, especially, were like, ‘OK, cool, you seemed like one of the guys already,’” says Army National Guard member Adrian Rodriguez, who transitioned from female to male two years ago. “They were kind of expecting it.”

*Editor's note, January 22, 2019: This story has been updated to reflect the Supreme Court's ruling to allow the restrictions on transgender servicemembers to continue as the legal battle moves through lower courts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/08/3a08066e-3be6-4cf3-92c0-75a0b293c1e9/janfeb2019_n02_transgendermilitary_resize.jpg)