Traveling in Style and Comfort: The Pullman Sleeping Car

The 19th century’s definition of luxury came as a train car designed by a Chicago carpenter

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/6a/ff6ae55e-af61-457e-bce8-4a45e2e0c54b/pullman-1.jpg)

The holiday season just started and, like many of you, I’ve already spent way too much time in crowded airports, cramped airplane seats, and desolate, freezing train platforms. It wasn’t always like this. There was a time when we didn’t shove our faces with overpriced fast food before elbowing our neighbor out of the way to get the last spot in the overhead bin or the only train seat that doesn’t have a weird stain on it. Long distance travel (for those who could afford it) used to be different, civilized even. Back when railroads began stitching the United States together, one name was synonymous with comfortable train travel: Pullman.

George Mortimer Pullman (1831-1897) made his name famous as the designer of the eponymous sleeping car, which made its debut in 1865. But sleeping cars had been around since the 1830s - so what made Pullman’s stand out? Comfort. The older 24-person sleeping cars left a lot to be desired and savvy designers leaped at the chance to improve long-distance train travel. George Pullman was a cabinet-maker, engineer, and building-mover who first made a name for himself in Chicago by raising buildings above flood levels after the city raised its streets and sewers; his system involved hundreds of men using jackscrews to lift the building then shore up its foundation. Supposedly he did it so smoothly that businesses stayed open while their buildings were being raised. After a particularly uncomfortable train ride, Pullman, flush with cash and growing notoriety from his experience in Chicago, got the idea for his next venture.

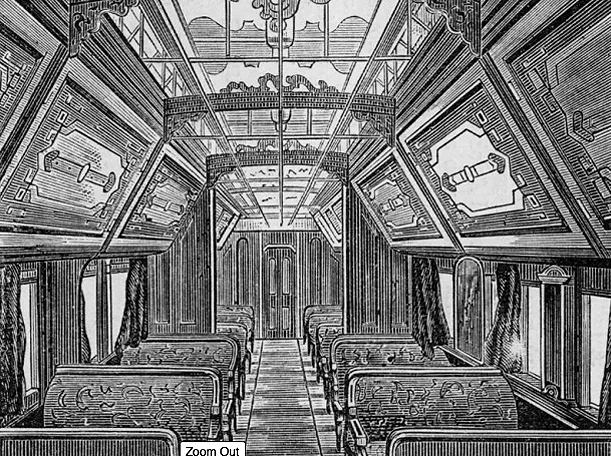

In 1858, he worked with the Chicago and Alton Railroad Company to redesign and remodel two of their 44-foot-long passenger coaches. These prototype Pullmans were very basic and, though a slight improvement over existing stock, a far cry from the luxurious train cars that would come to define the Pullman brand: hinged seats transformed into lower berths, while iron upper berths were attached to the ceiling by ropes and pulleys; curtains provided a modicum of privacy; small toilet rooms bookended the passenger area. The cars were not a success. Pullman moved on to other ventures but was drawn back to the train industry four years later. This time, however, he tried a different tactic: creating luxury models.

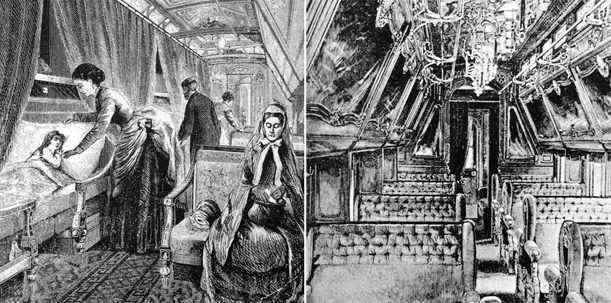

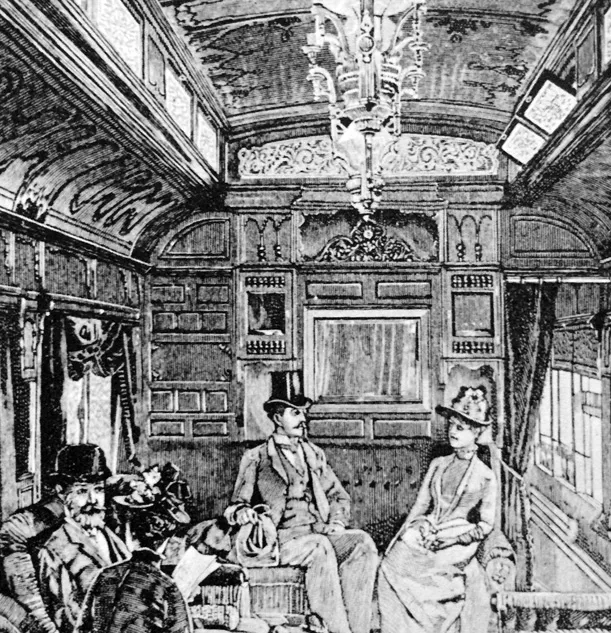

The Pioneer, as he dubbed his second design, was wider and taller than anything that came before and used trucks with rubberized springs to reduce bouncing and shaking. Thick curtains or silk shades covered the windows and chandeliers hung from the ceiling, which was painted with elaborate designs. The walls were covered in a rich dark walnut, the seating was covered in plush upholstery, and the fixtures were brass. During the day, the sleeper looked like a regular, if especially lavish, passenger car, but during the night it transformed into a 2-story hotel on wheels. Seats were unfolded into lower sleeping berths, while upper berths, instead of lowering from the ceiling on pulleys, folded out from it. Sheets and privacy partitions were installed by Pullman Porters to complete the effect. The only problem? The train didn’t exactly fit existing platforms. According to American Science and Invention, Pullman said, “My contribution was to build a car from the point of view of passenger comfort; existing practice and standards were secondary.” But this was 1865 and a national tragedy worked to Pullman’s advantage. After President Lincoln’s assassination the government elected to use the luxurious Pullman car for the last leg of his funeral train, requiring the renovation of every station and bridge between Chicago and Springfield. The publicity turned the Pullman sleeping car into an overnight success.

The train that transported Lincoln was soon put into commercial service. And, of course, civilized travel came with a slightly steeper price tag. But in the 19th century, and even into the 20th, long-distance train travel was almost exclusively enjoyed by the wealthy and the growing middle class. And though the Pullman Sleeper required a small additional fare, a berth wasn't unreasonable for people who could afford to travel far enough to need one. As the rail network grew, so did Pullman's empire. He rapidly expanded his enterprise and by 1867, he was running nearly 50 cars on three different railroads. He also developed some new designs: a hotel car, which was basically a Manhattan apartment on wheels, a parlor car, a dining car, and, perhaps most importantly, a train vestibule, which made it easy to safely move from one train car to another. After losing a patent suit related to his folding berth design, Pullman bought all his rivals' patents to further solidify his empire and the dark green pullman sleepers became ubiquitous on trains across the country. As decades passed, the designs became more ornate as Pullman's personal taste continued to shape Americans' idea of luxury - perhaps to a fault, as some women's magazines of the late 19th century objected to the ostentatious interiors as violations of good taste.

Unfortunately, bad taste isn't the only offense for which Pullman is remembered. The company has a long and complex relationship with African Americans. Famously, it was a calculated incident on a Pullman car that launched the landmark 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which ultimately established the "separate but equal" doctrine that would not be legally repudiated until the 1950s. But long before Plessy sat in a "whites only" car and long after the Supreme Court made their decision, Pullman Porters dealt with inequality on a daily basis. Though travelers favored the cars for their luxurious accommodations and services, the Pullman staff did not enjoy comparable luxuries. And though the company was both praised and derided for the hiring of African Americans at a time when few jobs were available to them, advancement for the "Pullman Porters" was almost unheard of. What's more, they worked long hours, received low wages, and were often treated poorly by passengers.

Although Pullman eventually became a sort of power-mad baron of his railroad empire, whose name is forever attached to unfair labor practices and a disastrous railroad strike, his contributions to the passenger train industry defined the way the nation traveled for nearly a century and continue to make holiday vacationers nostalgic for a time when long-distance travel could actually be an enjoyable experience.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)