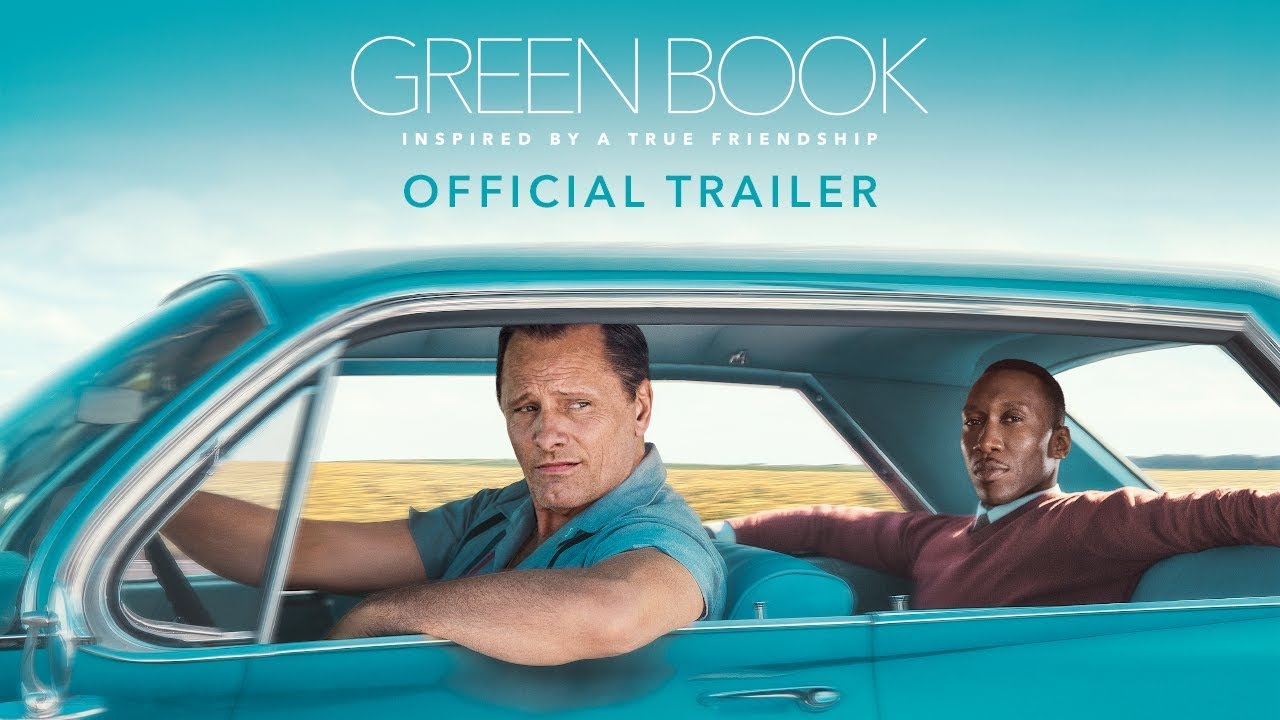

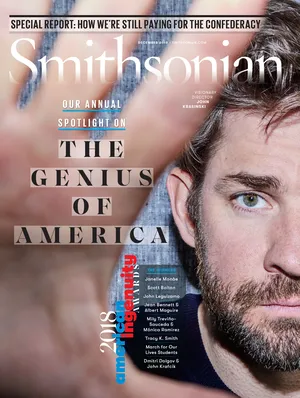

The True Story of the ‘Green Book’ Movie

Jazz, race and an unlikely friendship inspire the new film about navigating Jim Crow America

:focal(1250x2237:1251x2238)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/74/89746707-beb4-405c-ba9c-39b92ab3c4a3/dec018_b06_prologue.jpg)

It was well after dark on a Saturday night in January 1963 when the Don Shirley Trio took the stage in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The program of show tunes, jazz and classical music, the local paper reported, was “brilliant and exciting and warmly received by the large crowd.” But its famed leader and pianist, Don Shirley, who was black, knew his welcome was conditional. A hateful sign stood at Manitowoc’s city limits: “N-----, don’t let the sun go down on you in our town.”

When the trio set out on another tour later that year, Shirley hired a white driver, a gregarious Italian-American bouncer known as Tony Lip, to handle problems that might arise in the “sundown towns” of the North and the Jim Crow-era South. “My father said it was almost on a daily basis they would get stopped, because a white man was driving a black man,” recalls Lip’s son Nick Vallelonga, who has turned their journey into Green Book, a new film garnering Oscar buzz.

Vallelonga was 5 years old when his father headed out on the road with the pianist. After they returned more than a year later, the men lived their separate lives—Shirley played to acclaim in Europe and Lip became an actor—but they remained friends. As a child Vallelonga visited Shirley in his studio in Manhattan and heard stories about their trip. “That’s an unbelievable movie,” he remembers thinking. “I’m gonna make it one day.” In his 20s, Vallelonga, an actor and occasional screenwriter, interviewed his father and Shirley about how these two men from starkly different backgrounds navigated the racism they encountered. But Shirley stipulated that he didn’t want the story told until after his death.

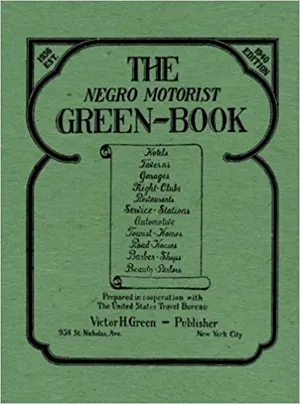

Both men passed away in 2013, and those conversations, along with letters Lip wrote his wife, form the basis of Green Book, which stars Mahershala Ali as Shirley and Viggo Mortensen as Lip. The title is a reference to The Negro Motorist Green Book, a travel guide for African-Americans published from 1936 to 1967 that promised “vacation without aggravation.”

Making the film more than half a century after the events it depicts hasn’t muted its powerful message about overcoming prejudice. Lip “was a product of his times. Italians lived with Italians. The Irish lived with the Irish. African-Americans lived with African-Americans,” Vallelonga says. The trip “opened my father’s eyes...and then changed how he treated people.”

The Negro Motorist Green-Book