Two Men and a Portrait

One wondered how an artist brings paint to life. The other showed him

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Thomas-Buechner-Bill-Zinsser-portrait-631.jpg)

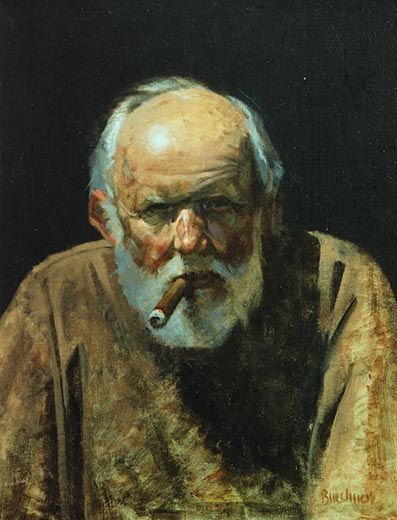

The American painter Thomas S. Buechner is best known for his portraits. His is the portrait of Alice Tully that hangs in Alice Tully Hall, in Lincoln Center, and his portrait of a teenage girl named Leslie is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In a long career of painting more than 3,000 pictures he has also found time to be the founding director of the Corning Museum of Glass, director of the Brooklyn Museum and president of Steuben Glass. He is also a teacher and a writer; his book How I Paint is a model of explanatory prose. He is also, less pertinently, my second cousin; our German-American grandmothers, Frida and Louise Scharmann, were sisters.

Over the years Tom has occasionally asked me to be his editor, most recently on the catalog for a museum exhibition of 175 of his works that chronologically tell the story of his life as an artist. Putting that jigsaw puzzle together was a complex task, and afterward Tom said, "I don't know how to thank you." I told him I was just glad we had been able to solve the problem. Then he said, "Would you like me to do your portrait?" I said, "Oh, no." WASPs are trained not to put people to any extra trouble.

But that night my wife said, "It would be nice to have a portrait by Tom." Of course she was right, so I called Tom back, and we agreed that I would come to Corning, the city in south-central New York where he has long lived, and spend two days sitting for him.

"I'll be asking you a lot of questions," he said. That sounded ominous. I've always thought of portrait painters as unlicensed psychiatrists, using their eyes instead of their ears to read the human heart; I doubt if Rembrandt's sitters had many secrets he didn't know about. What would it be like to have my 80-year-old cousin reading my 83-year-old face and putting onto canvas what he saw written there?

I decided to bring along my reporter's notebook and do a portrait of my own. It would be a triple portrait. One would be of Tom Buechner and his methods as a portrait painter. One would be of myself as I sat and thought my thoughts of time and mortality. And the third would be of the portrait as it gradually came to life.

Corning is a small city best known as the locale of the 156-year-old Corning Glass Works. I got there by taking a six-and-a-half-hour bus ride from New York City, arriving in late afternoon. Tom picked me up at my hotel to take me to his studio. He looks like an old German professor: white beard, metal-rimmed glasses, amused blue eyes. He has looked that way since his 50s; he seems to have always wanted to look older and to feel more German than he is. He has spent the last 18 summers teaching in Germany, and one of his amusements is to paint his idea of the grotesque figures of Teutonic mythology in the operas of his favorite composer, Richard Wagner.

I, meanwhile, have always wanted to look younger than I am and to feel 100 percent American. In a lifetime of travels I've avoided the homeland of the Buechners and the Scharmanns and the Zinssers: too much anger over World War II. But otherwise Tom and I are similar in our values and are connected by a bond of trust and affection. I had no fears about putting my life in his hands.

"The first step is to take some photographs of you," he said as we drove to his house, which was tucked into a hillside several miles outside town. His studio is an extension of the house—a lofty space with an angled ceiling and a huge window that looks out on pure nature: woods, birds, deer. (My office, in mid-Manhattan, looks out on the cars and buses of Lexington Avenue.) The studio was immaculate, every paintbrush clean, every tube of paint neatly resting in its ordained place.

Hanging on one wall were several portraits of successful-looking men that Tom had recently completed. These commissions—of CEOs, board chairmen, college presidents, headmasters—are a portrait painter's meal ticket. Tom has done 327 of them, including many women and children. When the mighty chiefs retire, it is a common custom to order a likeness that will gaze down on future generations from the oak-paneled walls of clubs and boardrooms and college halls. Knowing this, the chiefs arrange their features for posterity, their visage serious, their suits and shirts and ties suitably sober.

For my portrait I was dressed in my lifelong uniform: odd jacket, pressed charcoal-gray pants, white Brooks Brothers button-down shirt, conservative tie, sneakers. Seemingly casual, the look is carefully chosen to express who I think I am.

I also always wear a hat.

"I still remember, back in the '60s," Tom said, "when I was director of the Brooklyn Museum and you were on the board, all the other trustees came to the meetings in an overcoat and you wore a parka. Today you're nicely dressed, but you're wearing sneakers. It gives you a boyish look. It's also a screw-you look: ‘You may think I'm a preppy, but I'm a different kind of preppy.'"

My portrait, we agreed, would be of medium size—not the large whaling-captain size—and would be vertical, ending above the waist. "The first decision is always about where," Tom said. "I figure out where things are going to go on the canvas—it's like a line map—and where the contrasts are going to be. The usual tendency is to start with the eyes because they demand the most attention; we communicate with our eyes. When I was a kid my father advised me to ‘Start with the eyebrows; then you'll know where the eyes should go.' There's no basis for that whatever. In your case the eyes are not as important as where the necktie is going to be, because that necktie, against the white shirt, is the strongest contrast in the picture."

We tried different poses, Tom taking a digital photograph of each, until we found the one we liked best—the body slightly tilted to the right, the head tilted slightly to the left. The photograph of that pose, greatly enlarged, would be Tom's point of reference when he did the painting. Portrait painters have used photographs as an aid since the days of Thomas Eakins, in the late 19th century, and today they paint almost exclusively from photographs; 21st-century man is too busy to sit still for an artist. But Tom likes to paint from life as often as he can. "A photograph doesn't have presence," he said. "A person is a living, changing, evolving thing—which is much more exciting."

"The first thing I have to do," Tom said, "is to make a compositional sketch: this is where the head goes. The shape of the head and the way we carry it on our shoulders are the essential elements in recognizability. You'd recognize me from the back, a block away, by my silhouette. The most important job for me is to achieve a shape that you'd be recognized from: What is the essence of you? The biggest part of your likeness is the shape of your head, the length of your neck and your posture—not your eyes and nose and other features."

He showed me some one-minute pencil sketches he makes at airports and in meetings—widely different men and women. "I know a lot about these people," he said. "They all have a distinctive head shape, and each one carries it on the neck in a characteristic way. Remember Audrey Hepburn, how lovely she was? It was partly because of the way her very long neck positioned her head."

The photographing done, we called it a day and went out to eat; I would start sitting for my portrait in the morning. Actually, Tom didn't call it a day. At dinner he was still working, studying my smallest move.

When I reported for duty the next morning, Tom, consulting the photograph, had situated my portrait on the canvas, which he had already painted gray-green. It was an outline drawing, simple as a comic strip, but even in that primitive form the finished portrait was visible. Now Tom was ready to start on me. He sat me on a stool and put the photograph beyond me—"quite far away," he said, "because I only want to use it to get the sitter's body language, not the details. I don't think you can build a portrait out of details.

"For me, portraits fall into two general groups," he explained. "One is about a moment in time—a situation in a specific context. The other is about a person alone.

"The first category is epitomized by Sargent's painting of a woman reading to a boy. That's the specific context. If you signed up for a portrait by Sargent, you signed up for 60 sittings; it could take more than a year. Children really sat, and often they clearly would like to be somewhere else. That kind of portrait can also include furniture or clothes, or catch a gesture or a fleeting smile. Sargent really captured those incredible moments.

"The other kind of portrait is about a person alone—a person for whom time has been stilled. It's epitomized by Rembrandt, or Velázquez, or Ingres. I prefer that approach, partly because it enables me to focus on one thing at a time, separating design and form and color into three successive stages. But mainly I use it because when I'm painting someone, I don't want anything to distract me from that person. I put the sitter alone in dark, empty space. The stark background both startles and focuses attention: you see only the person. That creates a unique situation because in our daily lives we never see anybody out of context, including ourselves. Have you ever hung a piece of black velvet behind you and looked at yourself in the mirror? We are each of us quite alone, and that's what I try to paint."

That was a sufficiently terrifying thought to take into my first posing session; there would be no escaping aloneness. I tried to compose my features into the expression we had caught in the photograph and awaited my fate. Tom lit a cigar, chomped on it purposefully, selected a brush and went to work. Now he really looked like an old German professor.

"I know in advance," he said, "that you have to look wise, kind, experienced and humorous. You have to look like a guy who's been around—a guy who knows his way. I'll think of other ways you have to look as I go along."

I tried to look wise, kind, experienced and humorous, my mouth in a slight smile to lighten the gravity of the occasion. Humor is the lubricant of my life, and I wanted that in the picture. But I also wanted its opposite: authority and accomplishment. Above all, I wanted independence: the suggestion of a life lived with originality and risk.

I was born into the Northeastern establishment and have never quite stopped trying to pretend that I was not. During World War II, I left the cocoon of Princeton to enlist in the Army and learn about the wider world—which, as a G.I. in North Africa and Italy, I did. Home from the war, I didn't go into the 100-year-old family shellac business, William Zinsser & Co., as I was expected to do, being the only son, but skated out on the uncertain ice of journalism, uprooting my life four or five times to try a new direction when the work ceased to be satisfying. I've taken pleasure in being a lone cowboy, making my own luck. Could Tom also put that in his picture?

He was off to a fast start, putting paint on the canvas with strokes that were swift and sure. He was totally at home in what he was doing, like any artist or artisan—jazz musician or auto mechanic or cook—who has been there a thousand times before. He worked partly from the photograph and partly from my head, only occasionally asking me to sit still. Otherwise I was free to ask him questions, which he answered while continuing to paint.

"The hardest thing for a painter," he told me, "is to create what he wants, not what he sees. He can build what he wants out of what he sees. That's when a painter starts to become an artist—when he starts to deal with what's in his mind, not just with what he sees. You have to bring something to the party. Students are so eager to record what they see that they don't think about what they want. Do they want to just copy a photograph? Why would they want to do that? They've got the photograph."

Our first session, Tom explained, was about design. "I try to decide what's going to be dark and what's going to be light. What are the major contrasts? That's what's going to make the painting—that's the essential composition."

After several hours Tom declared the morning session over, and I took a look at the portrait. A design had been established. The left side of the face was somewhat dark, and some hills and valleys had begun to appear on the cartoon-strip countenance. The skeleton on the canvas had come partly to life. The colors were muted—umber and gray-green—but at least there was blood in his system. Definite progress.

We broke for lunch and a siesta, and at 2 o'clock Tom was back at his easel, a new cigar lit. "This second session is about form," he said, "I want to make the portrait start to look three-dimensional by adding strong lights and darks." I had noticed that Tom was a little lower than I was, and I wondered how he had arrived at that angle of vision.

"It's nicer to look up to people than to look down on them," he said. "Our respective eye levels are as important in a painting as they are in life. It has a lot to do with how the artist thinks about his clients; when we look at a great painting by Rubens or Van Dyck, they place themselves lower than their subject. Sargent looked down on his children, but that was a charming reality—these are children. But when Velázquez painted the infanta he placed her at eye level, respecting her royalty."

The studio was lined with bookshelves full of art reference books and monographs, and occasionally Tom took one out to show me a painting that illustrated a point he was making. "Continuously studying other painters—Rembrandt, Titian, Sargent, Lucian Freud—reminds me about the power of simplicity," he said. "That has helped me to focus on the person rather than on the moment."

As the person being focused on, I realized that I really didn't know much about my face. The man who looked back at me from the mirror was just an unremarkable assortment of eyes, ears, nose and mouth—an amiable-looking chap, eager to please. What else was there to know?

"Your head is like a slightly tapered box," Tom said. "There are several characteristic head shapes—oval and teardrop and inverted teardrop, which is especially common: all those double chins and wattles. The pull of gravity is always working; when people gain weight it's not around the forehead. Your forehead is a topographer's dream. Ordinarily the skin just lies on the bone, nice and tight. But when you start to talk—to express yourself—your forehead comes alive. It makes all those wrinkles come into play. Old faces are very nice—there's so much going on. Look at what Rembrandt did in those last self-portraits."

Several hours had slipped by. I had been working so hard at my own craft—asking questions—that Tom hadn't asked many questions of his own. Perhaps I was afraid of being left alone with my thoughts. But then he said, "Have you considered who gets this painting when you're dead?" POW! I wasn't going to be let off easy after all. I had a brief vision of my grown children, Amy and John, fighting over my portrait—or, worse, not fighting over my portrait—and then I tried to push the subject out of my mind. But it kept sneaking back: the whole point of having a portrait painted is to leave a record behind. I felt both good and bad—good because I wanted to be remembered, bad because I didn't want to be dead.

Stage two ended, and I went over to see how my face had metamorphosed. It was still the same neutral color, but it was far more alive. Light, the painter's miracle tool, had come to the rescue, illuminating the right side of the forehead in a high shine. But the left side of the face was dark. Those were the contrasts Tom had mentioned, which I had never noticed in a lifetime of looking at portraits. I thought my face was light. I thought everybody's face was light. Now I saw that the interplay of shadow and light is what gives faces much of their interest.

The portrait now lacked only its third and last element: color.

The next morning, when I settled into my sitter's chair, I said, "So this morning is all about color?"

"This morning is all about paint," Tom said. "It's where the brushstrokes really show. I've got the ‘where' figured out—what the forms are like. I know the structure of the head. I know where I'm going. Now the important thing for me is the paint itself. I have to put this paint on, brushstroke by brushstroke. Nobody knows, looking at the finished picture, how much time I've taken between brushstrokes. When you look at a Sargent it just knocks you over with its spontaneity—the bravura brushstrokes. So you assume it was painted quickly—a la prima, as artists say. What you don't realize is that there may have been a lot of time between brushstrokes, in which he was just thinking about paint. He wanted the paint to be beautiful, just as a cabinetmaker wants the texture of his wood to be beautiful. Spontaneity itself has no value. Sargent wanted many sittings because he used them to practice—he wanted every stroke to appear right on.

"I try to apply the paint in such a way that I'm making an interesting physical object. The thing you fight against all the time is to not have the painting die on you—not to make the paint dull, or to lose the transparency or the vitality. What no painter ever wants to hear is: ‘I like it very much, but it really doesn't have Jean's sparkle.' Remember Sargent's famous definition: A portrait is a painting with something a little wrong with the mouth."

The odds against catching Jean's sparkle seemed to me to be high; rare is the family member who doesn't find something not quite right in a family portrait. I asked Tom what it was like to embark on such a skittish marriage every time a new patron signs him up.

"I have to please myself," he said. "That's what I must do. But my job is to please the client. Clients rarely know what they want, but they often know what they don't want. Wives also have very possessive feelings—here's a guy fooling around with my husband's face. But I always make it clear that the painting is for just one person—the client. If it's a portrait of a child, the child's mother can be the client. Mothers know more about how their children look than you do. They'll say, ‘I think George's cheeks are a little fuller than you have them,' or, if I've changed the clothing for aesthetic reasons, ‘He never wears a shirt like that.'

"When a CEO—or anyone else—comes to me to be painted, I'm looking for an idea. This assumes that I've met him; maybe we've had a meal. We chat. I ask questions, see what his interests are, how he reacts, laughs, makes a point. Just who is this person? I study his face. I'm very conscious of his bearing, how he holds himself. Is he old and tired? Is he alive? Is he intellectually curious about the world? One banker who was retiring had a strong idea about the kind of person he thought he was and wanted to be: without a jacket, a hands-on guy. When someone wants to be like something, it tells you a lot about them. I could make an image of you that people would say, ‘He must be a very funny guy,' or ‘He must be a pessimist.'"

"Is it necessary for a portrait artist to like the people he paints?" I asked.

"I've done very few people I didn't like," Tom said. "I think that gives me an edge because your attitude is what you really paint. Some wonderful things happen with portrait subjects. They're out of their depth—they're in the hands of someone else. You really don't want to get arrogant with your surgeon.

"There was one CEO I didn't like. He talked only about himself and his achievements, instead of having a conversation with me. When he saw the finished portrait he said, ‘You don't like me, do you?' I said, ‘I'm sorry you said that. There are many other painters I'd be glad to put you in touch with—the best.' But when he brought his wife to see the portrait she said, ‘You should look so good.'

"Some men refuse to be painted. But most of them are interested. They regard it as a certain kind of mystery. How did it happen? It's a two-person transaction. Painting people is what I most like to do. In one person we see all people, including ourselves."

One question Tom often asks executives and other leaders, he said, is: "Do you want to be painted as someone who has a question, or as someone who has an answer?" It's an elegant question, and I began to wrestle with it. The CEOs, I guessed, were answer types, and I didn't want to be associated with them: arrogant know-it-alls. I wanted to be a man who has a question. Much of what I know I've learned by asking a million questions.

And yet...as I watched Tom studying my face and making judgments of his own, I heard a voice saying, "Not so fast." For much of my working life I've been in a position of authority, starting in my mid-20s when I was an editor at the New York Herald Tribune. Later I edited several magazines and was master of Branford College at Yale. Since then I've kept busy writing books and teaching courses that are taken by people looking for answers on how to write. In none of those undertakings do I remember having an onset of shyness or doubt and thinking, "I can't do that." Obviously, I was also a man who liked to be in charge, and I told Tom he would just have to contend with that ambiguity. I don't think it came as news to him that the human face is a shifting sea of contradictions.

"Actually," he said, "that question is mostly a ruse to get people to think—to start using the muscles in their face. Your face right now is full of all sorts of ripples as you think about the question."

The morning ambled along, Tom applying brushstrokes with Sargent-like confidence. At one point he asked me to take a look at the color he had added. To my dismay, the face was quite pink, more Hallmark than Buechner, and the strength had leaked out of it. I told Tom I didn't like it. It was the only criticism I made of the portrait-in-progress.

"I thought you looked pale," he said. Whether this was an artistic or a medical opinion I didn't ask. Tom assured me he could correct it; it was just a glaze. "When my sitters make a complaint I always tell them, ‘Don't worry, it's only paint.'"

When I next saw the painting, at the end of the morning, the colors were true.

The portrait was now 95 percent done; Tom would do some final tinkering after I left, mostly on the clothes. "Painters leave out a lot of stuff," he said. "I could put the herringbone in your jacket and people would say, ‘You can see the herringbone.' But that's not what I'm about and it's not what you're about."

We had arrived at the dreaded moment when the sitter is asked to look at the portrait and the painter says, "What do you think?" Tom had put ten hours of his life into trying to sum up my life as he saw it summed up in my face. What if I had to tell him he had botched the job? ("I can't quite put my finger on it; there's something about the eyes.") I went over and looked at the man looking out at me from the easel. He was just what I thought and hoped I looked like. The brushstrokes of heavy paint had brought animation to the eyes and humor to the mouth. But it was only a suggestion of humor; the person in the portrait was ultimately a serious person. He looked more imposing than I felt.

Because it wasn't a full-length portrait, Tom hadn't been able to paint my signature sneakers. But he did have the next-best thing: my white button-down Oxford shirt and collar. That collar is one of the quirky affectations of the WASP oligarchy. It's not designed to lie flat and to look starched, but, instead, to have a bulge and to look unstarched. By buying that shirt the wearer also declares himself to be unstarched. The shirt in Tom's portrait is a perfect replication of the Brooks Brothers bulge and is the strongest identifying mark in his composition, along with the tie, which, I saw, was very slightly askew. Those two objects of clothing—shirt and tie—say as much about me as my sneakers.

"That tie is like an arrow," Tom said. "It's like a spear. A spear points. What does it point to? It points to the most important thing in the picture: you. There's a toughness and strength in you. But there's also a softness—a sensitivity to things; it's not all black and white. So I wanted to emphasize the curve in the lapel. A straight line is masculine, a curve is feminine; it's deeply psychological. Your head is tilted slightly, so it doesn't have that in-your-face abruptness. It acknowledges that you're human."

That afternoon I caught the bus back to New York, riding past fields and farms that I felt I knew from Tom's many arresting landscapes. I was contented; if painting a portrait is a two-person transaction, Tom and I had spent the two days well. He had given me a gift of myself, one that would outlive me. That made me feel a little less bad about being dead.

A few weeks later the finished portrait was shipped to our apartment in New York. Everyone who saw it—wife, children, family, friends—agreed that Tom had really "gotten" me, and I called to tell him how good they all thought it was.

"Well, if you ever want anything changed," he said, "just let me know and I'll come and fix it. It's only paint."

William Zinsser is the author of 17 books, including On Writing Well.