The Unlikely, Charming Designer Who Is Changing the Face of Gardening

With weeds, critters and Celtic symbols, Mary Reynolds is transforming what it means to garden

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/b3/6cb32a26-6315-4274-afc4-ff36c3da3d43/jun2016_e05_phenom.jpg)

On a recent spring evening, the landscape designer Mary Reynolds greeted admirers in West Cork, Ireland, looking like one of the nature spirits that inspire her work. She wore a flower-covered green dress, her auburn hair still damp and tousled from a dip in a forest pool. “I needed to immerse myself, to feel all those watery plants under my feet,” she confided. Then she turned to chat with an elderly man in Gaelic.

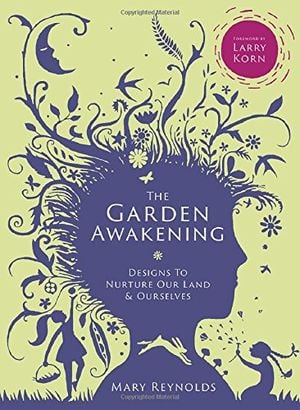

Throughout Europe, the ebullient Reynolds is famous for upending the gardening establishment with her subversive designs. A biopic based on her life, Dare to Be Wild, won an audience prize at the Dublin International Film Festival last year. Her new book, The Garden Awakening, sold out on Amazon UK the day of its release. “She’s really onto something,” says the Irish rock star Glen Hansard (best known for the movie Once). “We must nurture the wildness within us and see the beauty in the wildness without.”

Reynolds wasn’t always so wild. When she began designing gardens two decades ago, she was willing to create nearly anything a client wanted. “It could’ve been Japanese or Italian,” she says. “It could’ve been a Versailles garden in a 20-square-meter space.” Then one night in 2001, she dreamed she was a crow flying over an ancient forest. When she woke up, the message seemed clear: “I shouldn’t be making any more pretty gardens.”

After that, Reynolds focused on evoking mystical Irish landscapes. In 2002, at the age of just 28, she won a gold medal at the prestigious Chelsea Flower Show. Improbably, she beat Prince Charles and other luminaries with an entry that included weeds, rabbit droppings and giant stone thrones. The BBC and RTÉ invited her to film garden makeovers, and the British government commissioned a garden at Royal Kew. She drew inspiration for that work from the W.B. Yeats poem “The Stolen Child”: A path led visitors onto a moss-covered island shaped like a sleeping fairy woman. “Fairies, to me, embody the spirit of the land,” she says. “I wanted to lead people back to that place.”

Not everyone responded enthusiastically. “Some people at Chelsea said, ‘God, this is like a Celtic Disneyland,’” Reynolds recalls. A Dublin newspaper derided her for “Paddywhackery”—suggesting she’d created the garden equivalent of Lucky Charms.

But her work has profound meaning in a country where the Penal Laws long forbade Catholics from owning land. Ireland’s most celebrated gardens were English-designed, with sweeping lawns, manicured hedges and meticulous knots of roses. Reynolds invented a new, defiantly Irish aesthetic. For Chelsea, she enlisted the help of traditional stonemasons and plant experts. “We were quite a raggedy crew and a source of amusement to the other entrants,” recalls Christy Collard, a builder from the Future Forests Garden Centre in West Cork, who supervised the project. (He also became romantically involved with Reynolds, a major plot point in the film.)

It’s Reynolds’ approach to planting that truly sets her apart. She chooses varieties that naturally grow together and doesn’t believe in weeding or breaking up the soil. More esoterically, she asks the land what it wants to become. “The gardens we have now are controlled, manipulated spaces,” she told the crowd at her book launch in West Cork. “It’s like forcing a child to wear a pink tutu.”

What land really wants, says Reynolds, is to evolve into a forest. Her book (the U.S. edition comes out in September) lays out a ten-year plan that incorporates trees, root vegetables, creeping vines and optional chickens. After reading it, the British environmentalist Jane Goodall sent Reynolds a video message, gushing, “I love the way you bring in the spirituality of the land.”

At times, the book reads almost like an anti-gardening manifesto. But Reynolds doesn’t believe in letting the land revert to wilderness. “The soil would heal itself,” she says. “All the little creatures would come back. But something important would be missing: We wouldn’t be part of that process.”

The Garden Awakening