Unmanned Drones Have Been Around Since World War I

They have recently been the subject of a lot of scrutiny, but the American military first began developing similar aerial vehicles during World War I

![]()

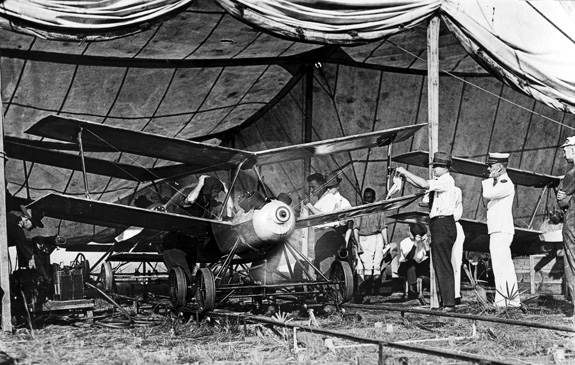

The Kettering “Bug” (image: The United States Air Force)

Recently, the United States’ use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has been the subject of much debate and scrutiny. But their history dates back a lot further than the war on terror. The first true UAVs, which are technically defined by their capability to return successfully after a mission, were developed in the late 1950s, but the American military actually began designing and developing unmanned aircraft during the first World War.

Military aviation was born during the years preceding the World War I, but once the war began, the industry exploded. Barely more than a decade after Orville and Wilbur Wright successfully completed the first documented flight in history –achieving only 12 seconds of air time and traveling 120 feet– hundreds of different airplanes could be seen dogfighting the skies above Europe. Mastering the sky had changed the face of war. Perhaps due to their distance from the fighting, the United States trailed behind Europe in producing military fliers but by the end of the War, the U.S. Army and Navy had designed and built an entirely new type of aircraft: a plane that didn’t require a pilot.

The first functioning unmanned aerial vehicle was developed in 1918 as a secret project supervised by Orville Wright and Charles F. Kettering. Kettering was an electrical engineer and founder of the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, known as Delco, which pioneered electric ignition systems for automobiles and was soon bought out by General Motors. At GM, Kettering continued to invent and develop improvements to the automobile, as well as portable lighting systems, refrigeration coolants, and he even experimented with harnessing solar energy. When the U.S. entered World War I, his engineering prowess was applied to the war effort and, under Kettering’s direction, the government developed the world’s first “self-flying aerial torpedo,” which eventually came to be known as the “Kettering Bug”.

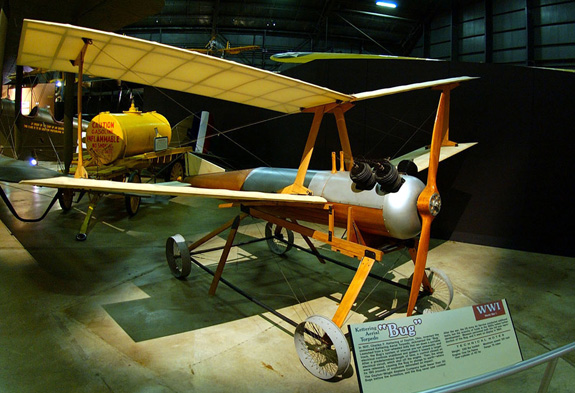

The Kettering “Bug” (image: The United States Air Force)

The bug was a simple, cheaply made 12-foot-long wooden biplane with a wingspan of nearly 15 feet that, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, weighed just 530 pounds, including a 180 pound bomb. It was powered by a four-cylinder, 40-horsepower engine manufactured by Ford. Kettering believed that his Bugs could be calibrated for precision attacks against fortified enemy defenses up to 75 miles away – a much greater distance than could be reached by any field artillery. The accuracy of this early “drone” was the result of an ingenious and surprisingly simple mechanism: after determining wind speed, direction, and desired distance, operators calculated the number of engine revolutions needed to take the Bug to its target; the Bug was launched from a dolly that rolled along a track, much like the original Wright flier (today, smaller drones are still launched from a slingshot-like rail), and, after the proper number of revolutions, a cam dropped into place and released the wings from the payload-carrying fuselage – which simply fell onto the target. To be sure, it wasn’t an exact science, but some would argue that drones still aren’t an exact science.

The Dayton-Wright Airplane Company built fewer than 50 Bugs but the war ended before any could be used in battle. That might be for the best. Much like today, there was a lot of doubt about the reliability and predictability of the unmanned aircraft and the military expressed concern about possibly endangering friendly troops. After the war, research into unmanned aircraft continued for a short time, but development halted in the 1920s due to the scarcity of funding and research on UAVs wasn’t seriously picked up again until the outbreak of World War II. Although by today’s standards, the Kettering Bug has more in common with a guided missile than a drone, its conception as a pilotless plane represents an important step in the historical development of unmanned aerial vehicles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)