Unprecedented Billboard Campaign Puts Spotlight on Indigenous Artists in Canada

“Resilience” features artwork by 50 indigenous women supersized on billboards throughout Canada—from British Columbia’s coast to Newfoundland’s eastern tip

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/f3/a0f376cf-d7cf-4ff3-8e52-8f0ebe3361d0/nadyakwandibens.jpg)

On an early June evening, the three-paneled video billboard that towers over one of downtown Toronto’s busiest intersections shuffles through its usual advertisements. Drive a Mitsubishi Outlander, the billboard urges. Sign up for Bell service provider. Buy Gorilla Glue.

Suddenly, a different sort of image flashes onto two of the three screens: a photo of 10 women, pressed shoulder to shoulder on a brick-lined street. Some wear jackets and dresses influenced by Western fashion, others vibrantly colored items of traditional indigenous clothing. Each is looking directly into the camera and smiling, some faintly, others with big, beaming grins.

The billboard’s central screen proclaims the title of the image—“10 Indigenous Lawyers”—along with the name of the photographer and her heritage: Nadya Kwandibens, Anishinaabe.

Across the street, Kwandibens is standing with her face titled upward, watching as her art fills the billboard. She whips out her phone so she can capture the moment.

“That’s crazy!” she cries.

It’s a warm summer night in the city and Kwandibens is wearing half her hair in a long braid, with the other half buzzed short. Around her neck hangs a golden pendant spelling out “Kwe,” which means “woman” in Ojibwe.

Kwandibens, 40, has been taking portraits of indigenous people for the past 18 years. The work started as a hobby, but she soon realized that she had a talent for it — and a knack for putting people at ease, for cracking jokes until they flashed a perfect, candid smile.

She is among 50 artists who have contributed to “Resilience,” an innovative new exhibition that is bringing the art of indigenous women to 167 billboards across Canada this summer. Most of the billboards are digital and will be rotating through all 50 artworks until the beginning of August.

“[W]e have this wonderful dream,” says curator Lee-Ann Martin, who worked on the project in collaboration with Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA), an organization that supports women visual artists in Canada. She hopes that people taking summer trips along Canadian highways or making their regular commutes to work “will see these images up on a billboard and will go, ‘Wow!’”

Martin, who is Mohawk, is one of the country’s foremost curators of contemporary indigenous art. Over the course of her now three-decade career, she has worked with many indigenous artists—but never with 50 at one time. When MAWA asked if she would be interested in curating a nation-wide billboard campaign, she was eager to take up the challenge. The project, Martin knew, would offer unprecedented visibility to indigenous women’s art, which has long been underrepresented and excluded from the Canadian canon.

For many centuries, and in many places around the world, women artists have been denied the opportunities afforded to their male counterparts. But in Canada, indigenous women artists have faced a unique set of barriers. The first, Martin says, is that Western anthropologists and museum experts have historically categorized traditional women’s arts—like beading and sewing—as crafts, rather than fine arts. “[Indigenous] women’s art has always been undervalued because it didn't fit into these Western kinds of divisions,” she explains.

In 1965, the Canadian government established the Indigenous Art Center to preserve and promote contemporary art by indigenous people. But some women artists weren't able to take advantage of the center’s programs, according to Martin. Under the Indian Act, an 1876 law that patently sought to assimilate Canada’s First Nations People, indigenous women lost their native status if they married non-status men. Though this provision was abolished in 1985, among its numerous detrimental effects was the denial of government support to artists in this community.

A nation-wide billboard campaign, which will be seen by thousands of people every day, seemed like a potent response to years of marginalization. “Those [images] standing in billboard size—that couldn't possibly be done in the gallery and have the same stature and symbolism,” Martin says emphatically. Nor could a traditional show hope to reach the broad audience that will see “Resilience” this summer.

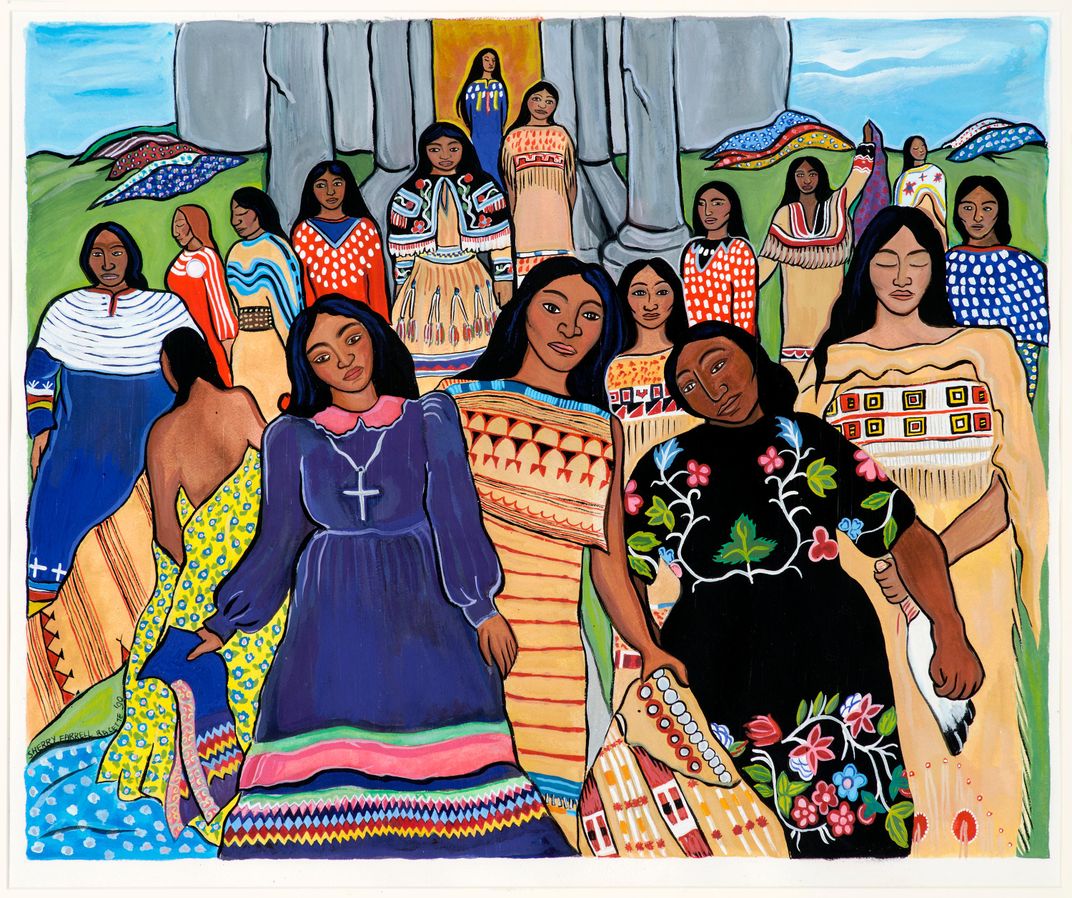

MAWA had worked with a Canadian billboard company previously, so securing the signage presented little challenge. Less simple was assembling 50 artworks that would both display nicely in billboard format and reflect the diversity of the country’s indigenous women artists—including those who identify as First Nations, Inuit and Métis, a term used to describe people of mixed indigenous and European heritage. Martin also wanted to capture both up-and-coming and established artists, acquiring images not only from some of the best-known in the field— Shelley Niro, Rebecca Belmore, Bonnie Devine—but also curating pieces from artists like Ursula Johnson and Jennie Williams who are making their mark on the Canadian art scene.

The “Resilience” billboards snake across a vast expanse of land, from the coast of British Columbia to the eastern tip of Newfoundland. They stand tall over small-town streets, bustling city centers and winding highways. Some locations are laden with profound significance; several billboards loom over the so-called “Highway of Tears,” a stretch of highway in British Columbia where at least ten indigenous women and girls went missing or were found dead between 1969 and 2006. Thousands of similar cases have been reported in Canada over the past few decades—a crisis that Assembly of First Nations national chief Perry Bellegarde once called “a national tragedy, but … an international shame.”

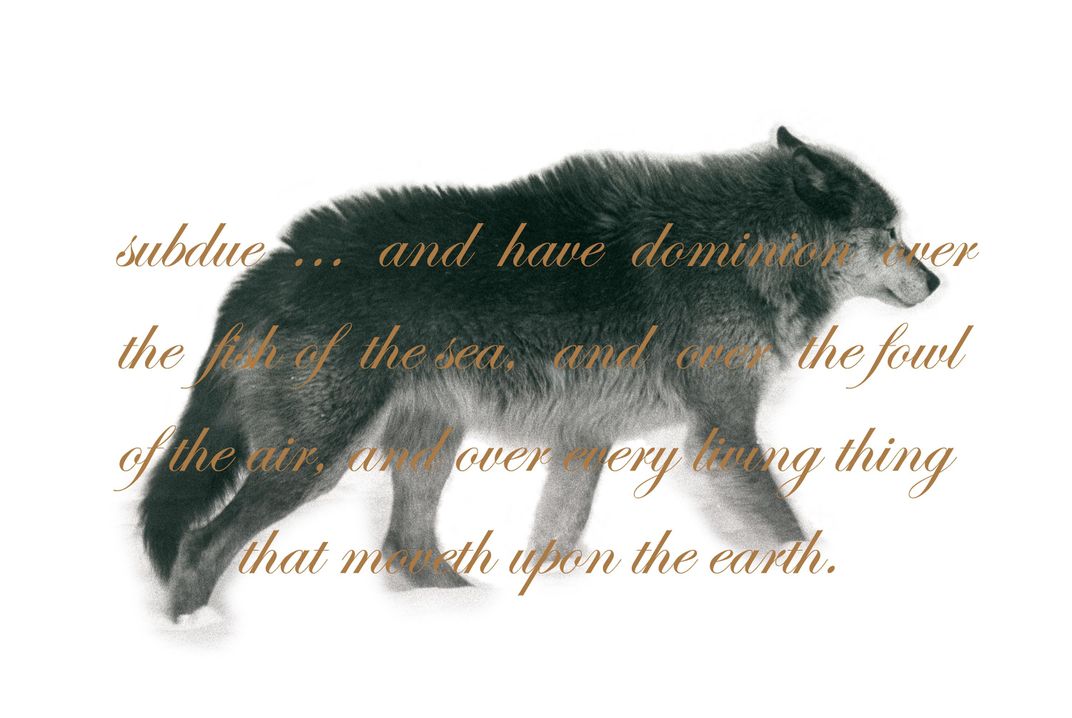

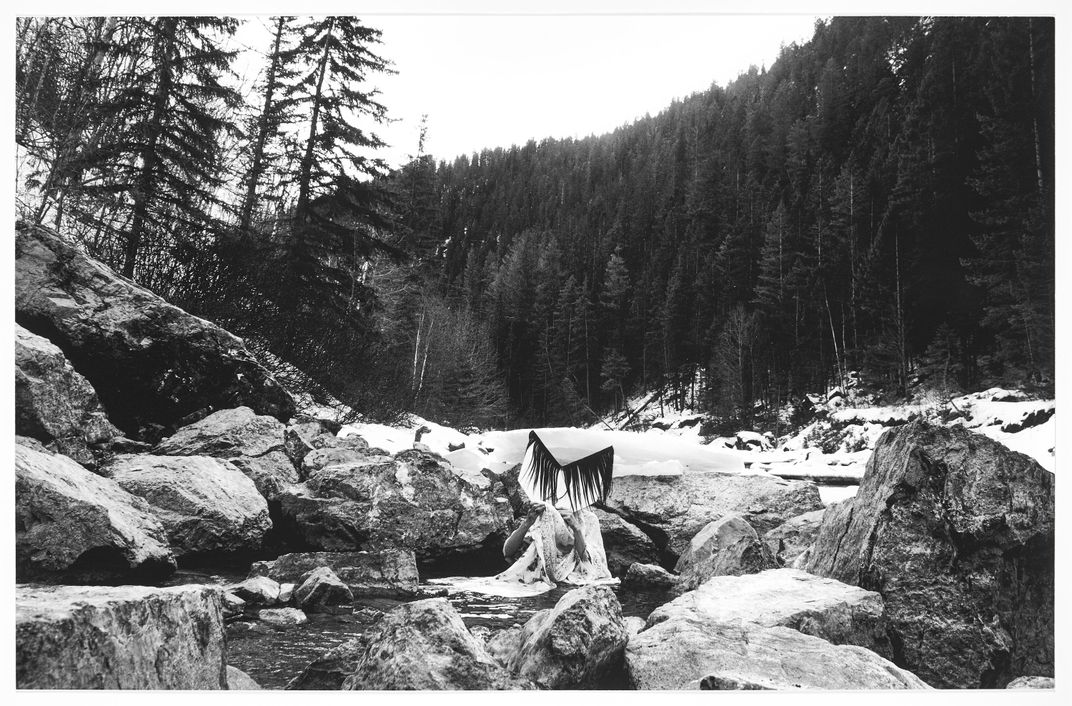

As its name suggests, however, “Resilience” is not about victimization. The artworks featured in the project are defiant, joyful, beautiful. There is Niro’s portrait of her mother, who strikes a pose on the trunk of a car, her arm flung coyly behind her head. Dayna Danger, a queer visual artist, contributed a photograph of a nude woman staring proudly into the camera as she clutches a pair of antlers to her body. Christi Belcourt offered an intricate painting of flowers, berries and birds, rendered in the style of traditional Métis beadwork.

“There’s so much going on in the [artworks],” says Michelle McGeough, a historian of indigenous art at the University of British Columbia . “[The artists] are taking on issues of appropriation, they’re taking on issues of the ways in which indigenous women are often viewed. I think it's so important for young, indigenous women to see this work in these public spaces.”

Lisa Myers, one of the artists featured in the project, believes it is important for non-indigenous people to see the work too. The day before the billboards were scheduled to go live, Myers anticipated the impact a project of this scale would have. “When they see a variety of artworks by indigenous women, they’re going to understand that there is a vital, very aware and informed voice that comes from indigenous women,” she says. “And not just indigenous women artists, but indigenous women in general.”

Her contribution to the billboards is a still from her 2013 video project “through surface tension,” which saw her plant a camera on the shores of various lakes and rivers in an attempt “to catch the horizon line of the water—something, she says, that “is actually kind of impossible.” The still shows the Ottawa River, shot low from the ground, with the green roofs of Canada’s parliament building peeking over a gelatinous swell of water. From this perspective, it looks as though the wave is about to swallow the seat of the country’s government.

“This is what rules,” says Myers, elaborating on the significance the image. “We have these two powers together in an image: [the water] is actually what rules us, these are the kinds of things that are much more important.”

Much of Myers’ art is preoccupied with the sustaining power of the natural world. Blueberries, for instance, feature prominently in her work. She films them, uses their pigments to dye screen prints and serves them to strangers as part of a performance series called “Shore Lunch.” Her interest in the fruit derives, in part, from her grandfather’s boyhood experience running away from a residential school; he survived on wild blueberries when he fled the school, traveling around 155 miles on foot.

Kwandibens’ work also reflects on ancestral ties to the land. Her contribution to “Resilience” is actually part of a larger series titled “Concrete Indians,” which features images of indigenous people in bustling city centers that sit on territory once held by their ancestors.

The women she assembled for “10 Indigenous Lawyers” — which she took on a brick-lined street in Vancouver, British Columbia, back in 2012 — all boast different backgrounds and areas of legal expertise, but the way she photographed them captures them as a united front.

“There’s something that happens when someone steps in front of the camera and they are so proud of who they are, they are so proud of what they do,” Kwandibens says. “For me, it’s about honoring their presence.”

As a child, Kwandibens spent years in foster care, an environment that she says “didn't necessarily yield such an awareness of identity, especially Native identity.” Now, she immerses herself in indigenous culture. She founded a photography company called Red Works and travels across Canada taking pictures in indigenous communities. Another of her series, “Outtakes,” is an exuberant collection of photos of indigenous people laughing. The project is intended, in part, to combat the stereotype of the “stoic Indian,” Kwandibens says. But she is not overly concerned with correcting outsiders’ perception of her culture.

“It’s always been about how we see ourselves,” she says as every 30 seconds or so, the “Resilience” billboard slides to a new painting, drawing or photo by a fellow artist that she knows or admires. “It’s about empowerment. It’s about uplifting our people.”

Correction July 14, 2018: This post originally misstated the distance walked by Lisa Myers' grandfather. It is 155 miles, not 15 miles.