Warhol’s Pop Politics

Andy Warhol’s political portraits anticipated today’s blurred boundaries between public office and stardom

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/warhol_631.jpg)

No doubt Andy Warhol, who died in 1987, would have reveled in our current media-saturated election. The artist’s own iconic images of 20th-century leaders inspired spirited debate about the pairing of politics and pop culture. So it is fitting that the first retrospective of his political works has been timed not only to coincide with this pivotal presidential election but also unveiled in New Hampshire, a state well-trod by political hopefuls and pundits. In “Andy Warhol: Pop Politics,” the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester exhibits more than 60 of Warhol’s paintings, prints, drawings and photographs, drawn largely from the collection of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

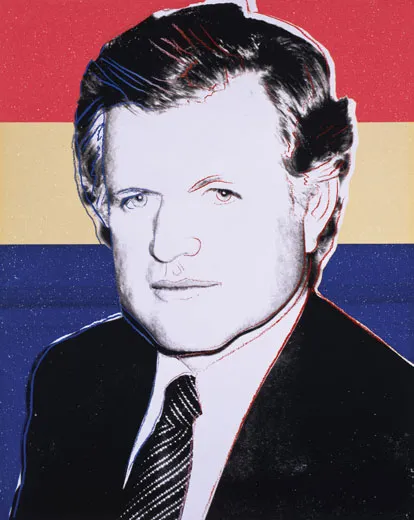

A commentary on the sociopolitical climates of previous decades, the exhibition also echoes today’s increasingly mass-marketed world and its effect on the ever-thinning line between public stature and stardom. “It points to the way in which these political figures are constantly shaping their image in the public eye,” explains exhibition curator Sharon Atkins. As an example, she cites “the message sent by Jimmy Carter commissioning Warhol to do his portrait [during 1976’s presidential campaign]. It was a very directed attempt … to reach the younger voters, and the voters of New York. It was a political hopeful deliberately using Warhol’s celebrity and status to try and position himself as a progressive candidate.”

It’s a strategy not lost on those nearing the finish line in the current race to the White House. “Certainly, Barack Obama has picked up on that,” Atkins says. “There is an Obama Art Report online on which artists can post work that they are creating to raise money for his campaign. And there is the Shepard Fairey poster [of Obama] that has gotten so much attention [and] in some ways links right back to Warhol and some of the work he was doing.”

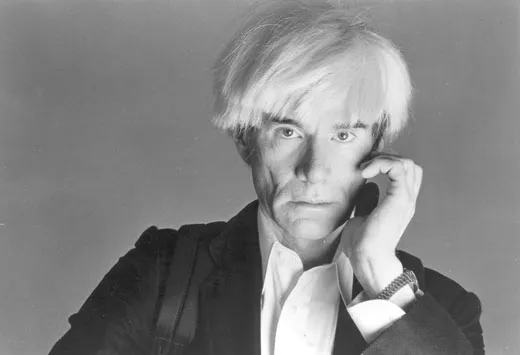

Warhol, born Andrew Warhola in 1928, studied graphic arts at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in his native Pittsburgh before working as a commercial artist and illustrator in New York City. He became a symbol of the counterculture movement in the early 1960s for his bold Pop Art works, which drew both praise and criticism for their similarity to commercial advertisements. By emphasizing techniques used by professional printers, and later employing studio assistants to help craft his works, he forced the question of what constituted art and transformed portraiture into a representation of an era. An eclectic artist, he remains best known for his renderings of American cultural staples, from Campbell’s Soup cans to Hollywood starlets and the political elite.

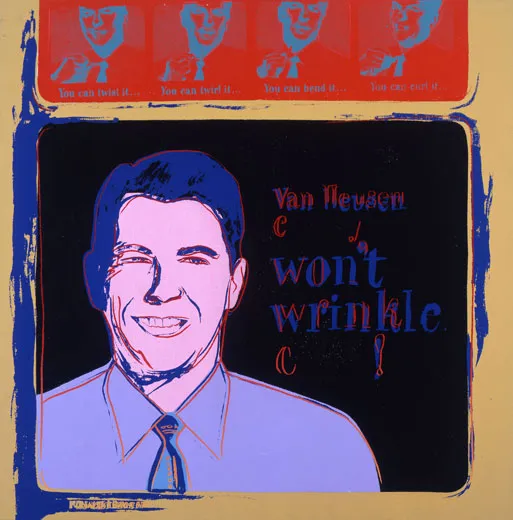

Warhol was captivated by the blurring boundaries between political stumping grounds and star-studded circles, where reinvention is an art and “politicians and actors can change their personalities like chameleons,” he once said. As a result, Warhol infused a sense of celebrity into his portraits, using jolting hues and exaggerated graphic elements while deliberately glamorizing facial features. “Warhol so idealizes his sitters,” Atkins says. “Pat Hackett [editor of the The Andy Warhol Diaries] mentions him working like a plastic surgeon, tightening skins, straightening noses, smoothing out wrinkles.”

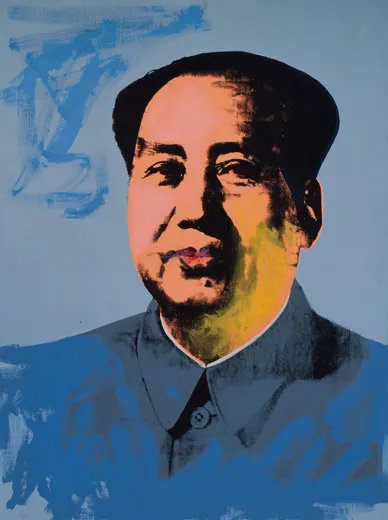

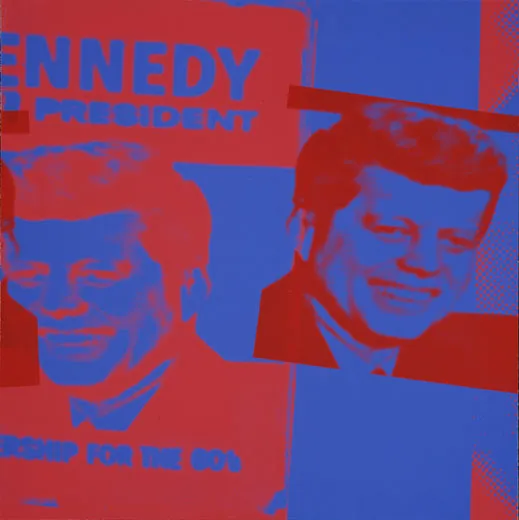

Another distinctive characteristic was his use of repeated images to suggest that the road to stardom is lined with relentless public relations campaigns. Warhol’s series on Chinese dictator Mao Zedong was a response to the Communist Party propaganda machine, which plastered China with a half-smiling image of the leader that was then replayed throughout the United States in news coverage of President Richard Nixon’s groundbreaking 1972 visit to that nation. Warhol’s series renders that ubiquitous image of Mao, but with facial features, clothing and backdrops in varying shades.

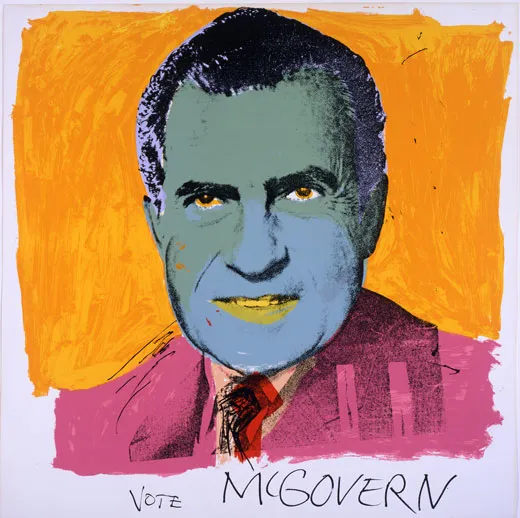

Warhol’s official position was political neutrality, but his party leanings are evident in one piece that resulted after the Democrats asked him for a contribution to George McGovern’s Presidential race against Nixon, the Republican incumbent. Titled Vote McGovern, 1972, the piece appears to be a visual invitation to contemplate the true colors of politics. It depicts Nixon with blazing yellow-rimmed eyes, lime-tinted lips suggesting foaming at the mouth, and a ghoulish green-blue facial cast. Warhol’s hand-written words beneath Nixon’s face read: “Vote McGovern.”

Warhol’s artwork represents a multilayered process that incorporated photographs, screen prints, paintings and graphics. Though he used scores of Polaroid images for later commissioned portraits, Warhol initially relied on “source images,” such as newspaper clippings, for many figure studies. One example is the centerpiece of the exhibition, Flash-November 22, 1963, which Warhol created in 1968 using Teletype reports to chronicle the fervor surrounding John F. Kennedy’s assassination and funeral. In one of the portfolio’s 11 works, a director’s clapboard is superimposed over Kennedy’s face, the scene marker serving as a metaphor for the endless takes played out in the persistent airing of the Abraham Zapruder film footage of the tragic event. “The repetition that Warhol responded to is very much connected to the sort of “YouTube” world that we live in now, where you can replay anything and everything over and over again,” Atkins says.

Flash was purchased in 2005 as New Hampshire’s Currier Museum headed into a $21 million expansion project, and while the intent initially was to bolster the gallery’s Pop Art collection, the acquisition soon became the focal point of what would be the gallery’s first major exhibition after reopening this year. “I was very surprised to see that the political portraits had never been looked at as a whole,” says Atkins, adding that when Currier officials realized the exhibition would coincide with the 2008 presidential election, “it was the perfect fit.”

“Andy Warhol: Pop Politics” can be viewed at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester through January 4, 2009. Gallery hours are 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Sundays, Mondays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturdays, with free admission offered from 10 a.m. to noon. In addition, the museum offers extended hours the first Thursday of each month from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. For more information, call (603) 669-6144 or go to www.currier.org.

The show moves to the Neuberger Museum of Art at Purchase College, the State University of New York, from February 15 through April 26, 2009.

Julia Ann Weekes is editor of the weekend arts section of the New Hampshire Union Leader in Manchester, New Hampshire.