Wernher von Braun’s V-2 Rocket

Although the Nazi “vengeance weapon” was a wartime failure, it ushered in the space age

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Object-at-Hand-NASA-Werner-von-Braun-631.jpg)

In 1960, Columbia Pictures released a movie about NASA rocket scientist Wernher von Braun called I Aim at the Stars. Comedian Mort Sahl suggested a subtitle: But Sometimes I Hit London.

Von Braun, born in Wirsitz, Germany, in 1912, had been interested in the nascent science of rocketry since his teen years. In 1928, while he was in high school, he joined an organization of fellow enthusiasts called Verein für Raumschiffahrt (Society for Space Travel), which conducted experiments with liquid fuel rockets.

By the time Germany was at war for the second time in a generation, von Braun had become a member of the Nazi Party and was the technical chief of the rocket-development facility at Peenemünde on the Baltic Coast. There he oversaw the design of the V-2, the first long-range ballistic missile developed for warfare.

The “V” in V-2 stood for Vergeltungswaffe (vengeance weapon). Traveling at 3,500 miles per hour and packing a 2,200-pound warhead, the missile had a range of 200 miles. The German high command hoped the weapon would strike terror in the British and weaken their resolve. But though the successful first test flight of the rocket took place in October 1942, operational combat firings—more than 3,000 in all—didn’t begin until September 1944, by which time the British people had already withstood four years of conventional bombing.

England wasn’t the only target. “There were actually more V-2 rockets fired at Belgium than at England,” says Michael Neufeld, curator of the V-2 on view at the National Air and Space Museum and author of Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War. “In fact, the single most destructive attack came when a V-2 fell on a cinema in Antwerp, killing 561 moviegoers.”

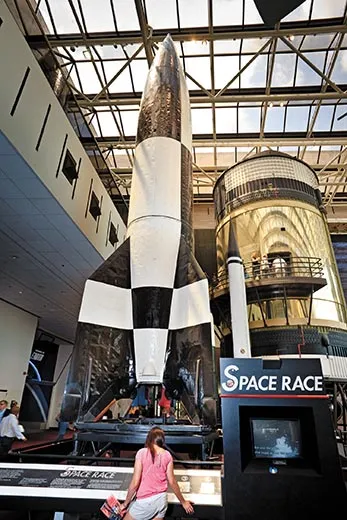

The Air and Space Museum’s V-2 was assembled from parts of several actual rockets. Looking up at it is not unlike looking up at a skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex: each is a genuine artifact representing the most highly evolved menaces of their eras.

When the war ended in 1945, von Braun understood that both the United States and the Soviet Union had a powerful desire to obtain the knowledge he and his fellow scientists had acquired in developing the V-2. Von Braun and most of his Peenemünde colleagues surrendered to the U.S. military; he would eventually become director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. There he helped design the Saturn V (in this case, the V stood for the Roman numeral five, not vengeance), the rocket that launched U.S. astronauts toward the moon.

During the war the Nazi regime transferred thousands of prisoners to the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp to help build the V-2 factory and assemble the rockets. At least 10,000 died from illness, beatings or starvation. This grim knowledge was left out of von Braun biographies authorized by the U.S. Army and NASA. “The media went along,” says Neufeld, “because they didn’t want to undercut U.S. competition with the Soviet Union.” Von Braun always denied any direct role in prisoner abuses and claimed he’d have been shot if he’d objected to those he witnessed. But some survivors testified to his active involvement.

For many years the V-2 exhibit omitted any mention of the workers who perished. But in 1990, Neufeld’s colleague David DeVorkin created a whole new exhibit, including photographs and text, to tell the complete story.

The assembled rocket wears the black-and-white paint used on test missiles at Peenemünde instead of the camouflage colors used when the V-2 was deployed on mobile launchers. Museum officials in the 1970s wanted to underscore the rocket’s place in the history of space exploration and de-emphasize its role as a Nazi weapon.

Neufeld says that contrary to popular belief, the V-2 was more effective psychologically—no one heard them coming—than physically. “Because the guidance system wasn’t accurate, many [rockets] fell into the sea or on open countryside....In the end, more people died building the V-2 rockets than were killed by them.”

For all its political complexities, the V-2 remains historic, Neufeld says, “because, even though it was an almost total failure as a military weapon, it represents the beginning of space exploration and the dawn of the intercontinental ballistic missile.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)