What a Physics Student Can Teach Us About How Visitors Walk Through a Museum

By sketching the movements of people at the Cleveland Art Museum, Andrew Oriani laid the groundwork for some deep insights into how art is appreciated

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120516024012Museum-Map-One-small.jpg)

What happens when we walk through a museum? In a class I’m teaching on American art in the age of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, this question came up. As a speculative exercise, we are designing an exhibition that involves trying to lay out a group of varied objects—including some that require close attention, such as architectural drawings—in a pathway that will make sense to visitors of different ages and levels of art experience.

To devise a good layout requires some understanding of what museum visitors do, and there’s surprisingly little literature on this topic. Most of the studies of museum-goers that I’ve seen rely on questionnaires. They ask people what they did, what they learned, and what they liked and didn’t like. No doubt there are virtues to this technique, but it assumes that people are aware of what they’re doing. It doesn’t take into account how much looking depends on parts of the brain that are largely instinctive and intuitive and often not easily accessible to our rational consciousness. Was there another mode of investigation and description that would illuminate what was actually taking place?

One of the students in my class, Andrew Oriani, is a physicist who spends much of his time doing mathematical proofs consisting of six or seven pages of equations. (He also has notable visual gifts: as a child he liked to draw elaborate cross-sections of ocean liners). He immediately grasped that the question we were asking was similar to one that comes up in physics all the time. How can one describe the activity of a group of subatomic particles that are moving unpredictably, seemingly erratically, in space? In physics this has become a subdiscipline known as statistical mechanics, and physicists have devised sophisticated tools, such as heat mapping, to describe how particles move in time and where they collect. In essence, physicists have found ways to describe and analyze events that are not specifically predictable, but that, when they’re repeated over and over again, turn out to obey recognizable principles. What would we find, Andrew asked, if we simply mapped the movements of visitors through a museum? What kinds of patterns would we find if we gathered enough data? Could we discern a recognizable pattern that had a shape? What would these patterns of movement reveal about the act of looking?

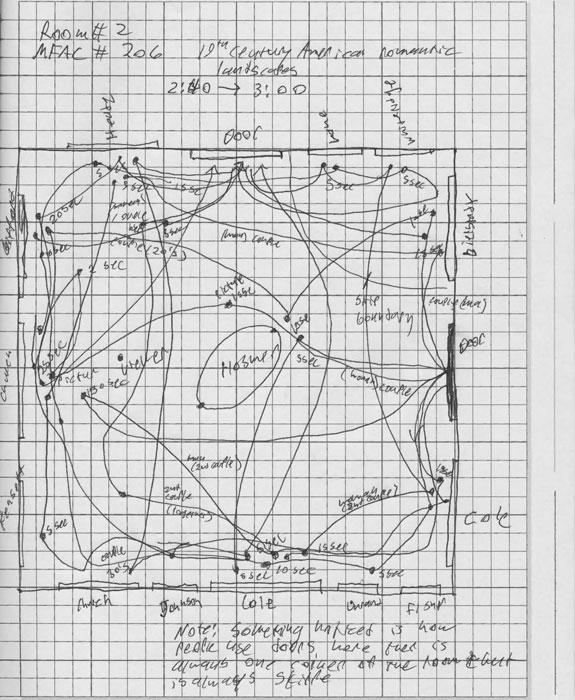

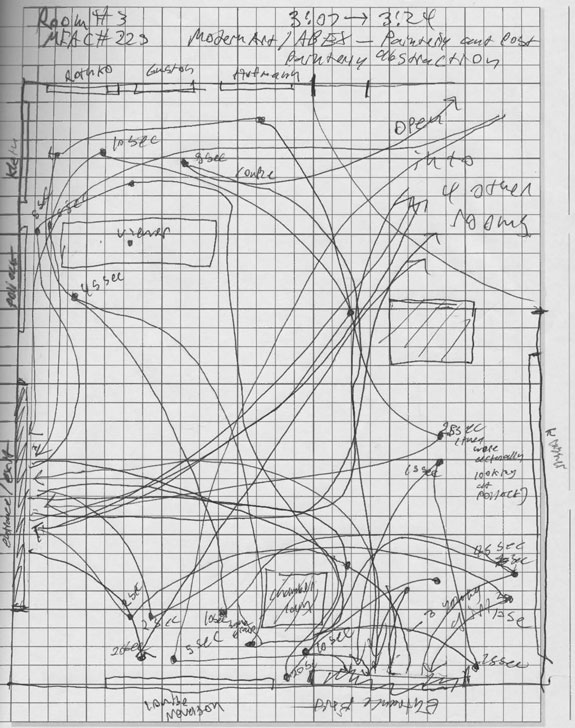

The preliminary results of asking these questions are provided by the three diagrams in this post. Perhaps there are studies of this sort that have already been published, but I haven’t come across them. Admittedly, Andrew’s diagrams are not precisely accurate—he worked freehand, without exact measurements—but for that very reason they have a wonderfully expressive quality: I must confess that part of what appeals to me about them is simply their beauty as drawings. Even without knowing what they’re about, we can sense that they contain information and they record something mysterious and interesting. In fact, what they record is not difficult to explain.

Basically, Andrew sat for about 20 minutes apiece in three galleries of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and as visitors entered he tracked their route and made notations of where they stopped and for how many seconds. A line indicates a path of movement. A dot indicates when someone stopped to look. The dots are accompanied by little notations indicating how many seconds the viewer stood still. There are also other scattered notations indicating the sex and general age of the people who were being tracked.

Movements in a gallery of 19th century Romantic landscapes. Drawings by Andrew Oriani

A more precise experiment would use some sort of electronic tracking device. You could record data in a fashion similar to a heat map, with spatial position indicated by lines and dots, and time indicated by a change of color. No doubt it would also be accompanied by demographic data, recording people’s age, sex, height, weight, income, profession, ZIP code and so forth. But what’s interesting to me is that even without such precision, this simple process encourages us to think about what museum visitors do in fresh and interesting ways. As usual, I have theories about the deeper implications of what Andrew recorded. By taking “psychology” out of the initial fund of data, and reducing the question to one of simple physical movement, the results end up illuminating what is actually taking place in psychological terms. But let me start with some observations.

- Museum visitors are surprisingly mobile: They move through a space in zigzagging patterns. One might even humorously point out that this is not the sort of walking in a straight line that police officers ask for when they’re conducting a sobriety test. This is the erratic track of people who are intoxicated. While rooms with a certain shape seem to affect patterns of movement, people make different choices and move differently. Some people like to turn left, others right; some people like to move in small increments along a wall, others to move across a room and back again. (With regard to people who move in opposite ways, I’ve always been impressed by how quickly my wife and I lose each other in a museum. Before cellphones, we would part ways in the first five minutes and it would often take two or three hours before we found each other again.)

- While most museum visitors would probably report they’ve looked carefully at art during their visit, in fact the looking time devoted to specific objects is often surprisingly brief. It’s often just two or three seconds, and seldom longer than 45 seconds. (If you asked them, they would probably say the time was much longer.)

- Different kinds of art seem to produce different patterns of movement. In the gallery of 17thand 18th century paintings, most visitors seemed to do a circuit of the room, moving from painting to painting. In the gallery with modern art, they tended to cross through the center of the room, looking first at what was on one wall and then what was on the opposite wall. While it would take a lot of study to isolate the key variables, even without knowing what they are, it’s clear that the movement of visitors is extraordinarily responsive to changes in the environment, including the placement of doorways and the arrangement of art.

- Even this quick study suggests that patterns of looking can be broken down into subsets. For example, in the 18th century gallery, women tended to move more regularly from one painting to the next, but to look at the individual paintings only briefly. Men tended to skip objects and follow a more erratic pattern of movement, but to stop for slightly longer when an object captured their attention. They also often chose vantage points farther away from the object. Not surprisingly, specific objects seemed to have particular appeal to particular groups. For example, a portrait by Benjamin West of his wife and child seemed to please middle-aged women, who often smiled. Men didn’t change their path or their expression.

With a larger body of data we could start to use the mathematical tools devised by physicists to analyze what was taking place. In the meantime, it’s rather fun to speculate about what Andrew has discovered so far. Perhaps recklessly, let me attempt to draw a few conclusions.

Movements in a gallery of Modern and Abstract art. Drawings by Andrew Oriani

Writers about art museums and visiting art museums tend to be moralists. They’re distressed that museum-goers are looking in a “superficial” way—that they look too quickly, that they don’t really “see,” and that they don’t get much understanding from the experience. In a certain way, this preliminary study confirms this complaint. Indeed, it suggests that visitors look even more quickly than one would have thought.

Is this bad? I’m not sure. What strikes me is that museum-going seems to connect with very deep-rooted and “primitive” instincts. In fact, the way that patrons go through a museum is very similar to the way a hunter-gatherer would move through grassland or a forest or streambed or ocean shore, moving back and forth from scanning the whole environment to closing in on some interesting plant, mushroom or living creature. The process of visual recognition and assessment occurs quickly. Think of beachcombing and the curious way in which a shell or piece of beach glass in our peripheral vision can suddenly become the center of our focus. We stoop to pick it up almost before we’re aware that we’re doing so.

Curiously, it seems to me that the popularity of museums is connected with something that many curators probably view as a nuisance and problem: that the pathway of the viewer is difficult to control. Curators and exhibition designers sometimes spend a lot of time trying to arrange paintings in a logical historical order, but in fact, most viewers don’t seem to obey these sequences. They may skip over things or go through the sequence backward. Yet what’s interesting is that at some level I think the curatorial arrangement does matter a great deal and people who go through an installation backward are nonetheless aware that the objects have been placed in some sort of deliberate scheme of organization. Much of the fun of a museum, however, lies in the fact that we’re allowed to choose our own pathway. In essence, our movement through a gallery is a way of arranging these objects in an order of our own choosing.

Andrew’s lines tracing movement have a certain parallel with the time-motion studies of Frank Gilbreth (1868-1924) and his wife, Lillian (1878-1972). The Gilbreths noted that in manual work, such as bricklaying, some workers laid bricks both faster and more accurately than others—significantly, the faster workers also did a better job. They then devised a method of fastening lights to arms and hands of such craftsmen, and of using stop-motion photography to trace the pattern of their movements. The Gilbreths discovered that certain patterns of movement, as revealed by an arc of lights, produce better work.

Is there a pattern of movement that reveals more intense looking—that perhaps distinguishes the art connoisseur from the mere amateur? I suspect that there is, although its most desirable pattern is probably almost the opposite of what the Gilbreths learned to favor. The Gilbreths discovered that good craftsmen work smoothly, in clean, direct movement, with little wavering or hesitation. With museum viewing, on the other hand, I suspect that back-tracking and hesitation are good—at least in the sense that they indicate serious interest, a sort of closing-in on the object that’s being hunted or examined.

I’m conjecturing a good deal, I must confess, but the lesson of these diagrams, if I’m correct, is that looking at art is not merely a logical process but also harnesses some of our deepest and most primitive sensory instincts. We were designed as hunter-gatherers. Museums allow us to go back to these roots—to learn and explore in the way that’s most natural for us.

It was rare for most visitors to stop for long. Would it be better if viewers stood still and looked more carefully? My own feeling is both “yes” and “no.” It seems to me that one of the pleasures of museum-going is to rapidly compare objects with one another. But yes, it would be nice if viewers sometimes stopped to look at an object very closely—and of course this is what the most gifted art historians do. To do this kind of close looking, however—looking for an hour or more at a single object—often requires a good deal of knowledge about the process of painting and the work of a particular artist. I suspect it also requires something a bit peculiar: a sort of infatuation.

Visual processing is one of the most complex of mental operations and by some estimates takes up about a third of our thinking process, although we’re almost unconscious of what’s happening. Taking long looks at something surely doesn’t follow a single pattern. Sometimes, I suspect, it becomes a sort of reverie, similar to spiritual meditation. At other times, I would propose, it is intensely exploratory, and if we mapped our eye movements we would discover that they have the same sort of unpredictable pattern that we discover when we chart the path of visitors to a museum. With darting movements, our glance is ricocheting across the picture surface, quickly taking in the whole thing part by part and then, somehow, assembling all these fragments into a unified gestalt. In some strange way, the mind synthesizes different acts of sight to create a sort of composite. In other words, the hunter-gather instinct is still at work. Our eyes are not contemplative grazers; they’re active hunters on the prowl. For an experienced art historian, for the passionate “long looker,” a single painting has become a vast landscape, filled with individual objects of interest that need to be cornered, approached and investigated.

Let’s not pretend that wandering through a museum or looking at a work of art needs to be done in a logical or linear way. As hunter-gatherers, we’re designed to work differently. It’s all right to zigzag.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)