What Camera?

Look what photographer Robert Creamer can do with a flatbed scanner

The sunroom in Robert Creamer's home is filled with dead and dying things: browning lotus leaves, heron bones, a halved nautilus shell exposing spiraling empty chambers, plates of desiccated irises, and other flora and fauna. Like most good photographers, Creamer, 58, is patient, waiting for that moment when his subjects "reveal something new," he says. Only then will he capture them in outsize photographs that he takes not with a camera but with a digital tool—a flatbed scanner.

Creamer, who has been professionally photographing architecture and museum installations for more than 30 years, migrated from camera to scanner—essentially an office color copier—over the past five years after clients began asking for digital images instead of the 4- by 5-inch film he had long used. After purchasing a scanner to digitize his negatives, he was hooked. "The detail was pretty phenomenal," he says. "I started scanning all kinds of things—a dead hummingbird, then tulips, oranges, bones, a snake that the cat dragged in."

Creamer's focus on detail underlies "Transitions: Photographs by Robert Creamer," an exhibition of 39 of his large-scale works now on view through June 24 at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C. The exhibition will be circulated to other U.S. cities by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service starting in the fall (see sites.si.edu).

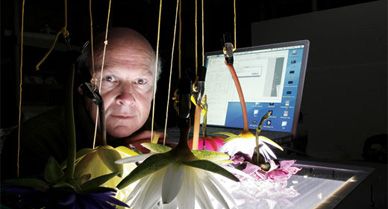

Like photography itself, scanning can be done by almost any novice, but Creamer has achieved a level of mastery with it. Through trial and error, he has adapted studio photographic techniques to the process. By training spotlights on objects at various angles, he says he's able to "paint with light." To avoid crushing delicate plants, he has removed the scanner's lid and rigged up a suspension system so that his subjects barely touch the surface of the machine.

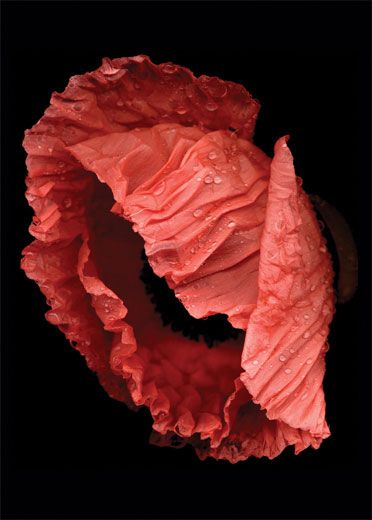

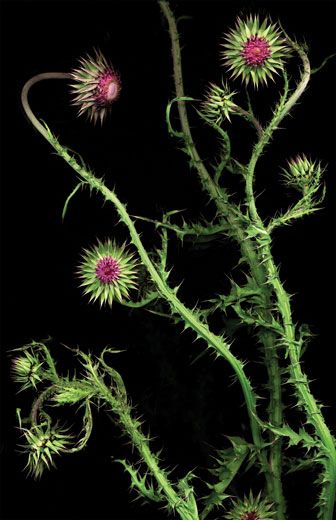

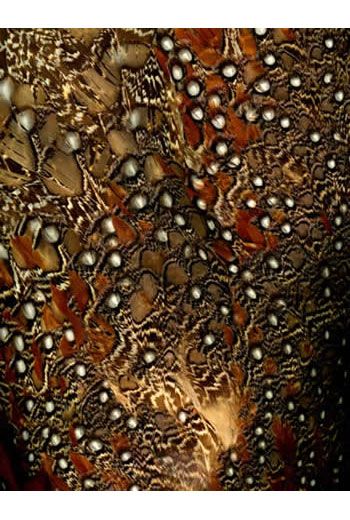

Creamer uses a black cloth tented over the scanner to create deep black backgrounds. The technique heightens the detail produced by the scanner, which generally renders sharper images than his camera does. Before burning an image to a CD, he previews it on his laptop and makes any adjustments he feels necessary. When satisfied, he loads it onto a Macintosh computer, does a bit of fine-tuning in Photoshop—a digital darkroom for photographers—and prints it. The results can be dazzling. The viewer's eye is drawn to an intricate network of leaf veins or, perhaps, a moonscape pattern of lotus seedpods or clumps of pollen clinging to a stamen. With large prints, the smallest details can be 20 or 30 times bigger than they actually are.

At that size, to Creamer's delight, the objects can appear otherworldly. "I could just say it's an emu egg," he says, pointing to a print of a greenish-black pitted oval, "but it isn't; it's like a Rothko painting." Similarly, Japanese maple seedpods look like winged moths in flight, and a peony mimics a pink-skirted Degas ballerina.

"I'm always checking my inventory of plants," Creamer says, holding a bouquet of fresh peonies. "As these dry, they'll slide through a color palette, from beautiful white-pinks to a dark brown. You have to be there. Sometimes it's just a matter of hours."

"Bob finds beauty in every phase of a thing's being," says Robert Sullivan, former associate director of public programs at NMNH. Sullivan granted Creamer access to thousands of the museum's preserved objects, from pressed flowers to animal skulls. "It was this search for beauty in the fading elegance of things that drew Bob to the museum collections," says Sullivan.

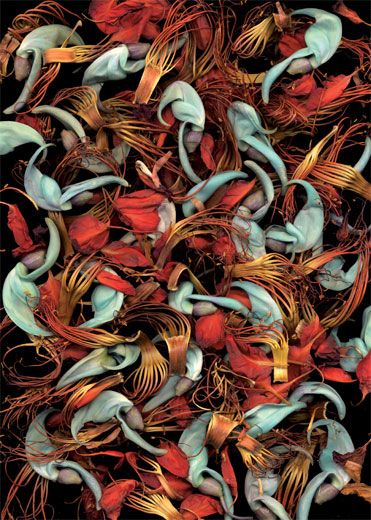

Creamer also made frequent visits to Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami, where he gathered plants for Fairchild Jade 2005, a 40- by 56-inch photograph in the exhibition. The image is an abstract tangle of turquoise and reddish-hued petals that Creamer arranged on a glass plate before putting them on his portable scanner. He kept the flowers for two years, periodically scanning them. In the first version, "they look so aquatic, it's like looking down into a coral reef," he says. "As they dried they became new material with new interpretations. They seemed to drift. They became skeletal." For a final scan, he burned them, capturing the plants in a ghostly swirl of smoke.

The scanner, Creamer says, allows him to "start with a complete blank slate" instead of "selecting a portion" of a given landscape to shoot with a camera. Ultimately, "it's not the process that is groundbreaking," he adds, "it's what's being captured that is groundbreaking." His old, large-format camera is now for sale.

Marian Smith Holmes is an associate editor at Smithsonian.