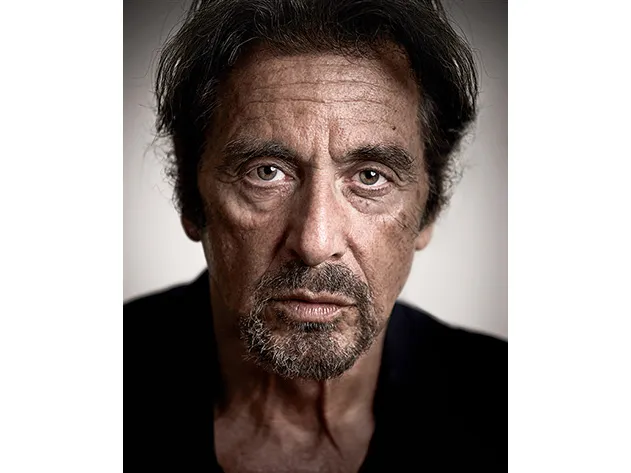

What Is Al Pacino’s Next Big Move?

For six years, the actor who made his mark as Michael Corleone has been obsessing over a new movie about that ancient seductress Salome

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/al_pacino_631x300.jpg)

Al Pacino likes to make trouble for himself. “Everything’s going along just fine and I go and f--- it up,” he’s telling me. We’re sitting on the front porch of his longtime Beverly Hills home in the low-key section known as “the flats.” Nice house, not a mansion, but beautiful colonnades of towering palms lining the street.

You’d think Pacino would be at peace by now, on this perfect cloudless California day. But dressed head to toe in New York black, a stark contrast to the pale palette of the landscape, he speaks darkly of his troubling dilemma: How is he going to present to the public his strange two-film version of the wild Oscar Wilde play called Salome? Is he finally ready to risk releasing the newest versions of his six-year-long “passion project,” as the Hollywood cynics tend to call such risky business?

“I do it all the time,” he says of the way he makes trouble for himself. “There’s something about that discovery, taking that chance. You have to endure the other side of the risk.”

“The other side of the risk?”

“They said Dog Day [Afternoon] was a risk,” he recalls. “When I did it, it was like ‘What are you doing? You just did The Godfather. You’re going to play this gay bank robber who wants to pay for a sex change? This is so weird, Al.’ I said, ‘I know. But it’s good.’”

Most of the time the risk has turned out well, but he still experiences “the other side of the risk.” The recent baffling controversy over his behavior during the Broadway run of Glengarry Glen Ross, for instance, which he describes as “like a Civil War battlefield and things were going off, shrapnel... and I was going forward.” Bullets over Broadway!

It suggests that, despite all he’s achieved in four decades of stardom, Al Pacino (at 73) is still a little crazy after all these years. Charmingly crazy; comically crazy, able to laugh at his own obsessiveness; sometimes, crazy like a fox—at least to those who don’t share whatever mission he’s on.

***

Actually, maybe “troubled” is a better word. He likes to play troubled characters on the edge of crazy, or going over it. Brooding, troubled Michael Corleone; brooding troublemaker cop Frank Serpico; the troubled gay bank robber in Dog Day Afternoon; a crazy, operatic tragicomic gangster hero, Tony Montana, in Scarface, now a much-quoted figure in hip-hop culture. He’s done troubled genius Phil Spector, he’s done Dr. Kevorkian (“I loved Jack Kevorkian,” he says of “Dr. Death,” the pioneer of assisted suicide. “Loved him,” he repeats). And one of his best roles, one with much contemporary relevance, a troublemaking reporter dealing with a whistle-blower in The Insider.

It has earned him eight Academy Award nominations and one Oscar (Best Actor for the troubled blind colonel in Scent of a Woman). He’s got accolades and honors galore.

In person, he comes across more like the manic, wired bank robber in Dog Day than the guy with the steely sinister gravitas of Michael Corleone. Nevertheless, he likes to talk about that role and analyze why it became so culturally resonant.

Pacino’s Michael Corleone embodies perhaps better than any other character the bitter unraveling of the American dream in the postwar 20th century—heroism and idealism succumbing to the corrupt and murderous undercurrent of bad blood and bad money. Watching it again, the first two parts anyway, it feels almost biblical: each scene virtually carved in stone, a celluloid Sistine Chapel painted with a brush dipped in blood.

And it’s worth remembering that Pacino almost lost the Michael Corleone role because he troubled himself so much over the character. This morning in Beverly Hills, he recounts the way he fought for a contrarian way of conceiving Michael, almost getting himself fired.

First of all, he didn’t want to play Michael at all. “The part for me was Sonny,” he says, the hotheaded older son of Marlon Brando’s Godfather played by James Caan. “That is the one I wanted to play. But Francis [Ford Coppola, the director] saw me as Michael. The studio didn’t, everybody else didn’t want me in the movie at all. Francis saw me as Michael, and I thought ‘How do I do this?’ I really pondered over it. I lived on 91st and Broadway then and I’d walk all the way to the Village and back ruminating. And I remember thinking the only way I could do this is if, at the end of the day, you don’t really know who he is. Kind of enigmatic.”

It didn’t go over well, the way he held back so much at first, playing reticence, playing not-playing. If you recall, in that opening wedding scene he virtually shrinks into his soldier’s uniform. “Everything to me was Michael’s emergence—in the transition,” he says, “and it’s not something you see unfold right away. You discover that.

“That was one of the reasons they were going to fire me,” he recalls. “I was unable to articulate that [the emergence] to Francis.”

Pacino admits his initial embodiment of Michael looked “like an anemic shadow” in the dailies the producers were seeing. “So they were looking at the [rushes] every day in the screening room and saying, ‘What’s this kid doing? Who is this kid?’ Everybody thought I would be let go—including Brando, who was extremely kind to me.”

Pacino was mainly an off-Broadway New York stage actor at that point, with only one major film role to his name, a junkie in The Panic in Needle Park. He was risking what would be the role of a lifetime, one that put him alongside an acting immortal like Brando, because he insisted that the role be a process, that it fit the method he used as a stage actor. He studied with Lee Strasberg, guru of Method acting, and he is now co-president of the Actors Studio. “I always had this thing with film,” he says. “I had been in one,” he says. “And [as a stage actor] I always had this sort of distance between myself and film.

“What kept me in the movie,” he recalls, “was my good fortune that they had shot the scene where Michael shoots the cop [early on, out of sequence]. And I believe that was enough for Francis to convince the powers that be that they should keep me.”

***

Pacino’s process gets him in trouble to this day. Before I even bring up the subject, he mentions the controversy surrounding the revival of David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross. He’d played the role of hotshot salesman Ricky Roma to much acclaim in the film, but when he took on a different part in a new version of the play—the older, sadder, loserish salesman played by Jack Lemmon in the movie—there was trouble.

The other actors were not used to Al’s extended “process,” wherein he needs prolonged rehearsal time to find the character and often improvises dialogue. The rehearsal process stretched into the sold-out Broadway previews, sometimes leaving the other actors—who were following Mamet’s script faithfully—lost. Which led to what are often euphemistically termed “creative differences.”

Thus the “Civil War battlefield,” Pacino says with a rueful shrug, the “shrapnel flying.”

The fact that he uses the term “civil war” is not an accident, I think—it was an exposure of the lifelong civil war within himself about when the “process” has to stop. Ideally for Pacino: never. And it sounds like he’s still got PTSD from the Glengarry Glen Ross civil war, can’t stop talking about it.

“I went through some real terrors,” he says. He wanted to discover his character in the course of playing him, wanted him to evolve, but “I’m a guy who really needs four months [to prepare a theater role]. I had four weeks. So I’m thinking ‘Where am I? What is this? What am I doing here? And all of a sudden one of the actors on stage turns to me and says, ‘Shut the f--- up!’”

Pacino’s response: “I wanted to say, ‘Let’s keep that in. But I figured don’t go there....And I kept saying, whatever happened to out-of-town tryouts?”

The play reportedly made money but didn’t please many critics. Pacino nonetheless discovered something crucial with his process, something about himself and his father.

“It’s the first time in many, many years I learned something,” he says. “Sometimes I would just say what I was feeling. I was trying to channel this character and...I felt as though he was a dancer. So sometimes I’d start dancing. But then I realized—guess what, I just realized this today! My father was a dancer and he was a salesman. So I was channeling my old man.”

He talks about his father, whom he didn’t know well. His parents divorced when he was 2, and he grew up with his mother and grandmother in the South Bronx. And he reminisces about the turning point in his life, when a traveling theater group bravely booked what Pacino remembers as a huge movie theater in the Bronx for a production of Chekhov’s The Seagull, which he saw with some friends when he was 14.

“And I was sitting with about ten other people, that was it,” he recalls.

But if you know the play, it’s about the crazy, troubled intoxication of the theater world, the communal, almost mafia-family closeness of a theatrical troupe. “I was mesmerized,” he recalls. “I couldn’t take my eyes off it. Who knows what I was hearing except that it was affecting. And I went out and got all Chekhov’s books, short stories, and I was going to school in Manhattan [the High School of Performing Arts made famous by Fame] and I went to the Howard Johnson there [in Times Square] at the time, to have a little lunch. And there serving me was the lead in The Seagull! And I look at this guy, this kid, and I said to him, ‘I saw you! I saw! you! In the play!’”

He’s practically jumping out of his porch chair at the memory.

“And I said, ‘It was great, you were great in it.’ It was such an exchange, I’ll never forget it. And he was sort of nice to me and I said, ‘I’m an actor!’ Aww, it was great. I live for that. That’s what I remember.”

***

That pure thing—the communal idealism of actors—is at the root of the troublemaking. The radical naked acting ethos of the Living Theatre was a big influence too, he says, almost as much as Lee Strasberg and the Actors Studio and the downtown bohemian rebel ethos of the ’60s.

In fact one of Pacino’s main regrets is when he didn’t make trouble. “I read somewhere,” I tell him, that you considered Michael killing [his brother] Fredo at the end of Godfather II a mistake.”

“I do think that was a mistake,” Pacino replies. “I think [that made] the whole idea of Part III, the idea of [Michael] feeling the guilt of it and wanting forgiveness—I don’t think the audience saw Michael that way or wanted him to be that way. And I didn’t quite understand it myself.

“Francis pulled [Godfather III] off, as he always pulls things off, but the original script was different. It was changed primarily because Robert Duvall turned down the part of Tommy [Tom Hagen, the family consigliere and Michael’s stepbrother]. In the original script, Michael went to the Vatican because his stepbrother, Robert Duvall/Tom Hagen was killed there, and he wanted to investigate that murder and find the killers. That was his motivation. Different movie. But when Bob turned it down, Francis went in that other direction.”

***

What emerges from this is his own analysis of Michael Corleone’s appeal as a character, why he connected so deeply with the audience.

“You didn’t feel Michael really needed redemption or wanted redemption?” I asked.

“I don’t think the audience wanted to see that,” he says. “He didn’t ever think of himself as a gangster. He was torn by something, so he was a person in conflict and had trouble knowing who he was. It was an interesting approach and Francis took it very—” he paused. “But I don’t think audiences wanted to see that.”

What the audiences wanted, Pacino thinks, is Michael’s strength: To see him “become more like the Godfather, that person we all want, sometimes in this harsh world, when we need somebody to help us.”

Channel surfing, he says, he recently watched the first Godfather movie again and he was struck by the power of the opening scene, the one in which the undertaker says to the Godfather, “I believed in America.” He believed, but as Pacino puts it, “Everybody’s failed you, everything’s failed you. There’s only one person who can help you and it’s this guy behind the desk. And the world was hooked! The world was hooked! He’s that figure that’s going to help us all.”

Michael Corleone’s spiritual successor, Tony Soprano, is a terrific character, but perhaps too much like us, too neurotic to offer what Michael Corleone promises. Though in real life, Pacino and Tony Soprano have something in common. Pacino confides to me something I’d never read before: “I’ve been in therapy all my life.” And it makes sense because Pacino gives you the feeling he’s on to his own game, more Tony Soprano than Michael Corleone.

As we discuss The Godfather, the mention of Brando gets Pacino excited. “When you see him in A Streetcar Named Desire, somehow he’s bringing a stage performance to the screen. Something you can touch. It’s so exciting to watch! I’ve never seen anything on film by an actor like Marlon Brando in Streetcar on film. It’s like he cuts through the screen! It’s like he burns right through. And yet it’s got this poetry in it. Madness! Madness!”

I recall a quote from Brando. “He is supposed to have said, ‘In stage acting you have to show people what you’re thinking. But in film acting [because of the close-up] you only have to think it.’”

“Yeah,” says Al. “I think he’s got a point there.”

It’s more than that in fact—the Brando quote goes to the heart of what is Pacino’s dilemma, the conflict he’s desperately been trying to reconcile in his Salome films. The clash between what film gives an actor—the intimacy of close-up, which obviates the need for posturing and overemphatic gesturing needed to reach the balcony in theater—and the electricity, the adrenaline, which Pacino has said, “changes the chemicals in your brain,” of the live-wire act that is stage acting.

***

Indeed, Pacino likes to cite a line he heard from a member of the Flying Wallendas, the tight-rope-walking trapeze act: “Life is on the wire, everything else is just waiting.” And he thinks he’s found a way to bring the wired energy of the stage to film and the film close-up to the stage. “Film started with the close-up,” he says. “You just put a close-up in there—D.W. Griffith—boom! Done deal. It’s magic! Of course! You could see that in Salome today.”

He’s talking about the way he made an electrifying film out of what is essentially a stage version of the play. (And then another film he’s called Wilde Salome about the making of Salome and the unmaking of Oscar Wilde.) Over the previous couple of days, I’d gone down to a Santa Monica screening room to watch both movies (which he’s been cutting and reshaping for years now).

But he feels—after six years—he’s got it right, at last. “See what those close-ups fix on?” Pacino asks. “See that girl in the close-ups?”

“That girl” is Jessica Chastain, whose incendiary performance climaxes in a close-up of her licking the blood lasciviously from the severed head of John the Baptist.

I had to admit that watching the film of the play, it didn’t play like a play—no filming of the proscenium arch with the actors strutting and fretting in the middle distance. The camera was onstage, weaving in and around, right up in the actors’ faces.

And here’s Pacino’s dream of acting, the mission he’s on with Salome:

“My big thing is I want to put theater on the screen,” he says. “And how do you do that? The close-up. By taking that sense of live theater to the screen.”

“The faces become the stage in a way?”

“And yet you’re still getting the benefit of the language. Those people aren’t doing anything but acting. But to see them, talk with them in your face....”

Pacino has a reputation for working on self-financed film projects, obsessing over them for years, screening them only for small circles of friends. Last time I saw him it was The Local Stigmatic, a film based on a play by British avant-garde dramatist Heathcote Williams about two lowlife London thugs (Pacino plays one) who beat up a B-level screen celebrity they meet in a bar just because they hate celebrity. (Hmm. Some projection going on in that project?) Pacino has finally released Stigmatic, along with the even more obscure Chinese Coffee, in a boxed DVD set.

***

But Salome is different, he says. To begin at the beginning would be to begin 20 years ago when he first saw Salome onstage in London with the brilliant, eccentric Steven Berkoff playing King Herod in a celebrated, slow-motion, white-faced, postmodernist production. Pacino recalls that at the time he didn’t even know it was written by Oscar Wilde and didn’t know Wilde’s personal story or its tragic end. I hadn’t realized that the Irish-born playwright, author of The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest, raconteur, aphorist, showman and now gay icon, had died from an infection that festered in prison where he was serving a term for “gross indecency.”

Salome takes off from the New Testament story about the stepdaughter of King Herod (played with a demented lasciviousness by Pacino). In the film, Salome unsuccessfully tries to seduce the god-maddened John the Baptist, King Herod’s prisoner, and then, enraged at his rebuff, she agrees to her stepfather’s lustful pleas to do the lurid “dance of the seven veils” for him in order to extract a hideous promise in return: She wants the severed head of John the Baptist delivered to her on a silver platter.

It’s all highly charged, hieratic, erotic and climaxes with Jessica Chastain, impossibly sensual, bestowing a bloody kiss upon the severed head and licking her lips. It’s not for the faint of heart, but Chastain’s performance is unforgettable. It’s like Pacino has been shielding the sensual equivalent of highly radioactive plutonium for the six years since the performance was filmed, almost afraid to unleash it on the world.

After I saw it, I asked Pacino, “Where did you find Jessica Chastain?”

He smiles. “I had heard about her from Marthe Keller [an ex-girlfriend and co-star in Bobby Deerfield]. She told me, ‘There’s this girl at Juilliard.’ And she just walked in and started reading. And I turned to Robert Fox, this great English producer, and I said, ‘Robert, are you seeing what I’m seeing? She’s a prodigy!’ I was looking at Marlon Brando! This girl, I never saw anything like it. So I just said, ‘OK honey, you’re my Salome, that’s it.’ People who saw her in this—Terry Malick saw her in [a screening of] Salome, cast her in Tree of Life—they all just said, ‘come with me, come with me.’ She became the most sought-after actress. [Chastain has since been nominated for Academy Awards in The Help and Zero Dark Thirty.] When she circles John the Baptist, she just circles him and circles him...” He drifts off into a reverie.

Meanwhile, Pacino has been doing a lot of circling himself. That’s what the second film, Wilde Salome, the Looking for Oscar Wilde-type docudrama, does: circle around the play and the playwright. Pacino manages to tell the story with a peripatetic tour of Wilde shrines and testimonies from witnesses such as Tom Stoppard, Gore Vidal and that modern Irish bard Bono.

And it turns out that it is Bono who best articulates, with offhand sagacity, the counterpoint relationship between Salome and Wilde’s tragedy. Salome, Bono says on camera, is “about the destructive power of sexuality.” He speculates that in choosing that particular biblical tale Wilde was trying to write about, and write away, the self-destructive power of his own sexuality, officially illicit at the time.

Pacino has an electrifying way of summing it all up: “It’s about the third rail of passion.”

There’s no doubt Pacino’s dual Salome films will provoke debate. In fact, they did immediately after the lights came up in the Santa Monica screening room, where I was watching with Pacino’s longtime producer Barry Navidi and an Italian actress friend of his. What do you call what Salome was experiencing—love or lust or passion or some powerful cocktail of all three? How do you define the difference among those terms? What name to give her ferocious attraction, her rage-filled revenge? We didn’t resolve anything but it certainly homes in on what men and women have been heatedly arguing about for centuries, what we’re still arguing about in America in the age of Fifty Shades of Grey.

Later in Beverly Hills, I told Pacino about the debate: “She said love, he said lust, and I didn’t know.”

“The passion is the eroticism of it and that’s what’s driving the love,” he says. “That’s what I think Bono meant.” Pacino quotes a line from the play: “‘Love only should one consider.’ That’s what Salome says.”

“So you feel that she felt love not lust?”

He avoids the binary choice. “She had this kind of feeling when she saw him. ‘Something’s happening to me.’ And she’s just a teenager, a virgin. ‘Something’s happening to me, I’m feeling things for the first time,’ because she’s living this life of decadence, in Herod’s court. And suddenly she sees [the Baptist’s] kind of raw spirit. And everything is happening to her and she starts to say ‘I love you’ and he says nasty things to her. And she says ‘I hate you! I hate you! I hate you! It’s your mouth that I desire. Kiss me on the mouth.’ It’s a form of temporary insanity she’s going through. It’s that passion: ‘You fill my veins with fire.’”

Finally, Pacino declares, “Of course it’s love.”

It won’t end the debate, but what better subject to debate about?

Pacino is still troubling himself over which film to release first—Salome or Wilde Salome. Or should it be both at the same time? But I had the feeling that he thinks they are finally done, finally ready. After keeping at it and keeping at it—cutting them and recutting them—the time has come, the zeitgeist is right. (After I left, his publicist Pat Kingsley told me that they were aiming for an October opening for both films, at last.)

Keeping at it: I think that may be the subtext of the great Frank Sinatra story he told me toward the end of our conversations. Pacino didn’t really know Sinatra and you might think there could have been some tension considering the depiction of the Sinatra character in Godfather. But after some misunderstandings they had dinner and Sinatra invited him to a concert at Carnegie Hall where he was performing. The drummer Buddy Rich was his opening act.

Buddy Rich? you might ask, the fringe Vegas rat-pack guy? That’s about all Pacino knew about him. “I thought oh, Buddy Rich the drummer. Well that’s interesting. We’re gonna have to get through this and then we’ll see Sinatra. Well, Buddy Rich starts drumming and pretty soon you think, is there more than one drum set up there? Is there also a piano and a violin and a cello? He’s sitting at this drum and it’s all coming out of his drumsticks. And pretty soon you’re mesmerized.

“And he keeps going and it’s like he’s got 60 sticks there and all this noise, all these sounds. And then he just starts reducing them, and reducing them, and pretty soon he’s just hitting the cowbell with two sticks. Then you see him hitting these wooden things and then suddenly he’s hitting his two wooden sticks together and then pretty soon he takes the sticks up and we’re all like this [miming being on the edge of his seat, leaning forward]. And he just separates the sticks. And only silence is playing.

“The entire audience is up, stood up, including me, screaming! Screaming! Screaming! It’s as if he had us hypnotized and it was over and he leaves and the audience is stunned, we’re just sitting there and we’re exhausted and Sinatra comes out and he looks at us and he says. ‘Buddy Rich,’ he says. ‘Interesting, huh—When you stay at a thing.’”

“You related to that?”

"I'm still looking for those sticks to separate. Silence. You know it was profound when he said that. 'It's something when you stay at a thing."'

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)