What Movies Predict for the Next 40 Years

From Back to the Future to the Terminator franchise, Hollywood has many strange and scary ideas of what will happen by 2050

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Blade-Runner-movie-631.jpg)

For a filmmaker, creating a futuristic world is a tricky task, especially if your crystal ball looks just a few years over the horizon. The challenges are varied – from dreaming up technological advancements, ages before their time, to predicting an approaching apocalypse (that also, hopefully, is ages before its time).

Over the course of the next 40 years, many cinematic visions will be compared to the reality of their time. Will they turn out like 2001, with its unfulfilled expectations of an outer-space-focused future, or like The Truman Show, prescient and a clear warning sign of things to come. From summer blockbusters to dystopian allegories to animated adventures, here is a selection of what Hollywood has predicted for the United States and the world from now until 2050:

2015: Released in 1989, Back to the Future Part II played with the space-time continuum as Marty McFly traveled forward to 2015, then back to 1955, then forward again to 1985. Its vision of the future, however, is a smorgasbord of whiz-bang inventions. In the fictional Hill Valley, California, of 2015, you can buy self-drying clothes, self-lacing shoes and drive a flying car. Books do not have dust jackets (but note: there still are books). In earlier drafts of the script, there was a plot line that involved a new form of credit card: your thumb. The most famous invention of 2015, though, is the “hoverboard,” a skateboard that levitates over the ground; at the time of the film’s release, many fans called the production studio asking where they could obtain one. Lastly, the Chicago Cubs finally end their century-plus quest to win the World Series in 2015.

A darker side of 2015 was predicted in Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop (1987). Detroit is in shambles, overtaken by crime and an evil corporation with plans to demolish the decrepit city center. Cops shot by nefarious crime bosses are resurrected as half-man, half-machine law-enforcement cyborgs. Though Detroit has had its share of troubles, will this be the future of policing? In the film’s two sequels that bring us to the close of the decade, the answer is “yes.”

2017-2019: Dystopia reigns in the late 2010s. Adapted from Cormac McCarthy’s novel, The Road (2009) was the bleakest of bleak films. An unnamed Man and Boy roam a post-apocalyptic earth (cause of the devastation unknown), avoiding the last remnants of humanity who are scavenging for any remaining sustenance, including human flesh.

“In the not-too-distant future, wars will no longer exist, but there will be rollerball,” reads the tagline of the 1975 film Rollerball. Forget soccer. In 2018, rollerball is the world’s most popular sport and competitor Jonathan E is its star athlete. Global corporations have ended poverty, cured disease and given society a great sport – except, it is all designed, in the words of John Houseman’s sinister villain, “to demonstrate the futility of individual effort.”

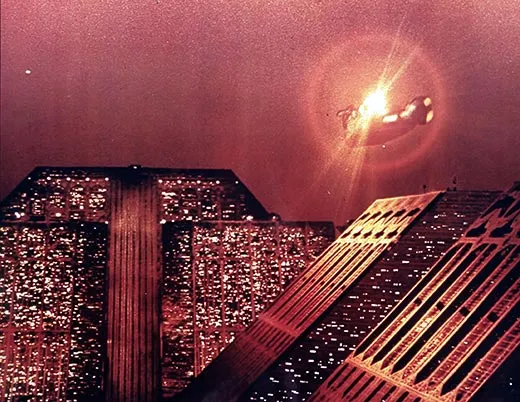

In Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s 1982 loose adaptation of a Philip K. Dick novel, by 2019, pollution and overpopulation have transformed cities such as Los Angeles into depressing megacities. Replicants – androids with superhuman strength yet visually indistinguishable from humans – are pursued by bounty hunters known as blade runners. Off-world colonies advertise a greater life via flying billboards. Animals are scarce and must be genetically engineered. And, once again, we have flying cars.

2020: A manned voyage to the Red Planet occurred in the near future, according to Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars. Released in 2000, the film portrays a trip to Mars ending in disaster in 2020 – though the rescue team makes a startling discovery about human origins.

2022: “Nothing runs, nothing works,” said a voiceover in a trailer for Soylent Green (1973). The world survives on rations of the titular food, produced by the behemoth Soylent Corporation. Pollution and overpopulation are again the culprits that have turned the world into a police state. Charlton Heston’s detective Ty Thorn traces a series of unsolved murders to the secret no one has lived to tell: “Soylent Green is people!” Even worse, with the oceans dying, it’s clear that not even Thorn’s discovery can change the course of civilization.

2027: While Children of Men doesn’t take place for another 17 or so years, the plot rested on developments that would be beginning now. Across the world, female infertility rates begin to decrease rapidly and by the end of the 2000s no more babies are born. In 2027, Baby Diego, the youngest man on the planet is stabbed to death at the age of 18. Director and co-writer Alphonso Cuarón’s dystopia reveals an England that has shut itself off from a world in chaos. In this 2006 movie, cars look mostly the same as today’s, but with no future generations on their way, what is the use in forging new technologies?

Also set in 2027, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) was one of the first, and most famous, visions of the future. The world according to Lang is run on machines, with masses of enslaved humans working tirelessly on them. Economic disparity turns into a Marxist nightmare – the upper class lives above the earth in luxury, while the working class lives below the surface.

2029: Through the four Terminator movies (and the short-lived television program), beginning in 1984, the basic premise remained the same: a war breaks out in 2029 between humans and self-aware robots bent on our destruction. The first movie had Arnold Schwarzenegger travel back in time as the Terminator to kill Sarah Connor, the mother of John Connor, leader of the 21st-century human rebellion. The sequels were variations on the theme, with Schwarzenegger switching from villain to hero. If Sarah and John Connor survive various attacks, we will rely on them to save the human race. Most of us don’t survive the nuclear holocaust initiated by the machines, but for those of us who join the resistance, John Connor is our leader.

2035: The themes of robots and the evil corporations who create them lived on in I, Robot (2004), an extremely loose adaption of a series of short stories by Isaac Asimov. In director Alex Proyas’ future, robots are household fixtures governed by the Three Laws of Robotics (one of the few holdovers from Asimov’s stories). As is often the case in our cinematic future, the robots rise up, but this time it is for our greater good. The robots decide that we have waged too many wars and have laid too much waste to the environment – they must step in and take control to save us from ourselves. Should Will Smith’s Det. Del Spooner succeed, however, the rebellion will be short-lived.

2037: Leave it to an animated film to predict a brighter future for us. In Meet the Robinsons (2007), people travel by bubbles or pneumatic tubes, cars are flying (again), and genetically enhanced frogs sing and dance. The skies are bright blue and the grass is vibrantly green. Life, in general, is good.

2038-9: Guy Fawkes failed in 1605 to blow up the British Parliament, but the vigilante “V” succeeded on November 5, 2039, after promising to do so on state-run television the previous year. V for Vendetta, the 2005 film adaption of Alan Moore’s graphic novel, is set in a United Kingdom ruled by a totalitarian regime. Years earlier, the threat of terrorism had placed the reactionary far-right Norsefire Party in power, but now, with “V” as the rabble-rouser of a popular revolt, normalcy may return to England – albeit without its iconic Parliament.

2054: Although Minority Report (2002) took place outside our window of the next 40 years, some of the technologies predicted are just too fascinating (and reasonably attainable) to ignore. In this scenario, also adapted from a Philip K. Dick work, retinal scanners are a part of life, allowing the local store to know your shopping preferences. They also allow the government to track you. Cars zoom down highways and up the sides of buildings; police use jet packs. Newspapers still exist, but are entirely digital. There are no murders in Washington, D.C., thanks to a pilot program of “pre-crime,” in which murders are stopped before they can happen – presuming that the system is perfect, which it never is.

Naturally, this will all be moot should the doomsayers prove correct and the world ends in 2012 by the disintegration of the Earth’s crust, à la Roland Emmerich’s 2009 movie, the catastrophe-ridden 2012. If a caldera in Yellowstone National Park starts to transform into a volcano, start worrying. The Mayans may have been right all along.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)