What Public Spaces Like Cleveland’s West Side Market Mean for Cities

They are more than just a haven for foodies — markets are “fundamental building blocks of urban life”

![]()

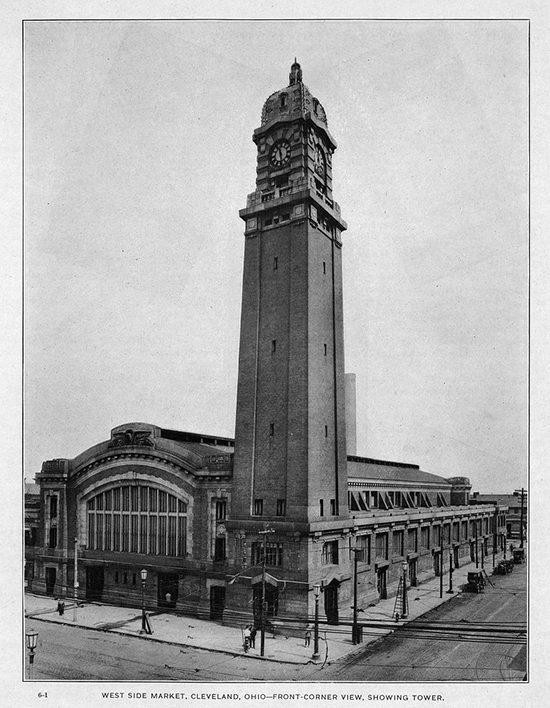

West Side Market, Cleveland, Ohio. (image: Terence Burlij/PBS NewsHour, CC)

We’ve been talking during the past week about various ways that cities reshape their identities and project them to the world. Chattanooga designed a typeface; Amsterdam developed a campaign slogan and installed colorful sculptures. For cities whose public image has suffered or whose anchor industries have closed down, this kind of intervention can breathe new life into the economy and kickstart cultural activity.

At the non-profit Project for Public Spaces, creative acts of urban planning and civic engagement are mission central. Project for Public Spaces (PPS) was founded in New York City in 1975, and has spent its decades cataloging, promoting, and helping to create public spaces that people naturally gravitate towards. The term of art is placemaking, and its successful implementation can be seen almost anywhere that an existing public space—a park, a plaza, a neighborhood, even a transit system—has become a prized community asset. In many instances, those places have also grown into critical features of a city’s brand—think Prospect Park in Brooklyn, or Jackson Square in New Orleans.

One of the focal categories on PPS’s list is the public market. Markets have long been an important organizing principle for infrastructure, traffic patterns, and human activity in a city, but in many places, the grand buildings that once housed central markets have gone neglected, and the businesses inside are long shuttered. Where public markets are still in operation or have been revived, however, it’s hard to find a stronger example of the power of placemaking.

PPS calls these places Market Cities, where public food sources “act as hubs for the region and function as great multi-use destinations, with many activities clustering nearby…Market Cities are, in essence, places where food is one of the fundamental building blocks of urban life–not just fuel that you use to get through the day.”

Among the stalls at Cleveland’s West Side Market (image: Mike Zellers)

The greatest public markets are the ones that simultaneously serve city residents’ daily food needs, while functioning as a tourist attraction for visitors who want to witness local culture in action. While brand strategists obsess over how to communicate “authenticity,” public markets are inherently one of the most authentic expressions of a place, and therefore an ideal symbol for a city to use when representing itself to the world—as long as they are thriving, of course.

There are a number of good examples of market cities in the U.S., but one of the best is Cleveland, where the century-old West Side Market has become a key engine in the city’s revitalization. The market building itself is one of Cleveland’s finest architectural gems—a vast, red-brick terminal with stunningly high vaulted ceilings, book-ended with massive, arched windows. On the ground, as the vendors will attest, is an open opportunity for small-scale sellers to establish themselves in the market economy and build a livelihood. And, following PPS’s definition as a hub from which other market activities spin out and cluster, the West Side Market is now just one node in a buzzing network of food-related endeavors—restaurants, farmers’ markets, urban farms—which are assembling into a whole new identity for the “Rust Belt” city.

Cleveland’s West Side Market in 1919 (image: Library of Congress)

This month in Cleveland, PPS will host their annual Public Markets Conference, an event design to help more cities leverage their markets as engines for urban growth. I’ll be attending the event to learn more about the role of markets in the city of the future, from Santa Monica to Hong Kong; and I’ll be touring Cleveland’s urban and rural food hubs to get a better sense of how it all links together in one American city. I’ll be writing more about my experiences right here in a couple of weeks. Stay tuned.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)