What Secrets Do Ancient Medical Texts Hold?

The Smithsonian’s Alain Touwaide studies ancient books to identify medicines used thousands of years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Medicine-Man-631.jpg)

In 2002, Alain Touwaide came across an article about the discovery, some years before, of a medical kit salvaged from a 2,000-year-old shipwreck off the coast of Tuscany. Divers had brought up a copper bleeding cup, a surgical hook, a mortar, vials and tin containers. Miraculously, inside one of the tins, still dry and intact, were several tablets, gray-green in color and about the size of a quarter.

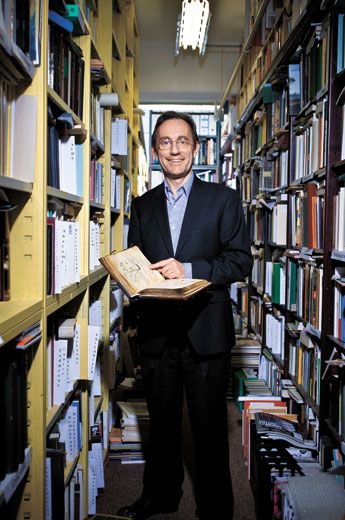

Touwaide, a science historian in the botany department at the National Museum of Natural History, recognized that the tablets were the only known samples of medicine preserved since antiquity. “I was going to do everything I could to get them,” he says.

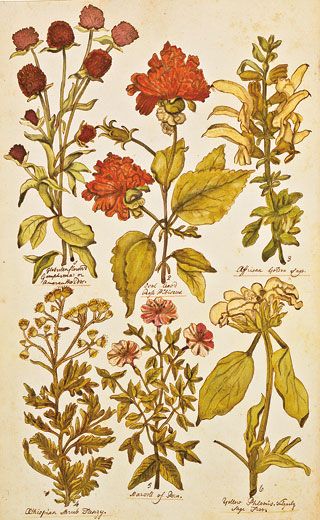

Touwaide, 57, has devoted his career to unearthing lost knowledge. He is proficient in 12 languages, including ancient Greek, and he scours the globe searching for millennia-old medical manuscripts. Within their pages are detailed accounts and illustrations of remedies derived from plants and herbs.

After 18 months of negotiations, Touwaide obtained two samples of the 2,000-year-old tablets from Italy’s Department of Antiquities. He then recruited Robert Fleischer, head geneticist at the Smithsonian’s Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, to identify plant components in the pills. Fleischer was skeptical at first, figuring that the plants’ DNA was long degraded. “But once I saw plant fibers and little bits of ground-up plant material in close-up images of the tablets, I started to think maybe these really are well preserved,” he says.

Over the past seven years, Fleischer has painstakingly extracted DNA from the samples and compared it with DNA in GenBank, a genetic database maintained by the National Institutes of Health. He has found traces of carrot, parsley, alfalfa, celery, wild onion, radish, yarrow, hibiscus and sunflower (though he suspects the sunflower, which botanists consider a New World plant, is a modern contaminant). The ingredients were bound together by clay in the tablets.

Armed with Fleisher’s DNA results, Touwaide cross-referenced them with mentions of the plants in early Greek texts including the Hippocratic Collection—a series loosely attributed to Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine. Touwaide found that most of the tablets’ ingredients had been used to treat gastrointestinal disorders, which were common among sailors. Afflicted seafarers, Touwaide speculates, might have diluted the tablets in wine, vinegar or water to ingest them.

This latest research will be added to the holdings of the Institute for the Preservation of Medical Traditions—a nonprofit organization founded by Touwaide and his wife and colleague, Emanuela Appetiti, a cultural anthropologist.

“The knowledge to do what I’m doing is disappearing,” says Touwaide, surrounded by his 15,000 volumes of manuscripts and reference books, collectively named Historia Plantarum (“History of Plants”). With manuscripts deteriorating and fewer students learning ancient Greek and Latin, he feels a sense of urgency to extract as much information as possible from the ancient texts. He says they tell stories about the lives of ancient physicians and trade routes and contain even such esoterica as an ancient system for describing colors.

“This is important work,” says Fleischer. “He is trying to tie all this together to get a broader picture of how people in ancient cultures healed themselves with plant products.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)