When “Danger” Is Art’s Middle Name

A new exhibit looks at the inspiration that comes from the clash of glory and catastrophe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/c5/2dc5de54-bb44-427c-88f3-b01893dfe8a4/man-in-blue-resized.jpg)

Even though its from the 1920s, Austrian designer Joseph Binder's poster "Gib acht sonst" ("Be Careful or Else … "), looks as if it could be an advertisement for one of today's Marvel films: a man in blue, with a red-and-white bolt of lightning shooting through his entire body. But the man is not, in fact, one of the “X-Men”: The image, commissioned by an Austrian accident prevention agency, was meant to warn people about the risk of electrocution when changing a light bulb. Homes wired for electricity were quickly becoming common in Europe at the time.

The image is one of roughly 200 works in a new exhibit, "Margin of Error," now open at Miami’s Wolfsonian museum at Florida International University in Miami Beach (the Wolfsonian is also a Smithsonian affiliate.) Through graphic and decorative art, photography, painting, sculpture, industrial artifacts and ephemera, the show explores cultural reactions—ranging from glorifying to terrifying—to major innovations in Europe and the U.S. between 1850 and 1950, including coal mines, steamships, airplanes, electricity, railways and factories. "Innovations that were 'on the margins' of society to begin with, as referenced in the title, had to earn the public's confidence, and sometimes failed. And, in another sense, that margin of error — those rare occasions when technology does fail it — is an area full of artistic potential

"It's a century when the products and processes of industry not only advanced but also became emblems that gave meaning to the world and our place within it," says curator Matthew Abess. "Yet, every step forward brings us that much closer to the edge of some cliff. We are in equal measures masters of the universe, and masters of its unmaking."

As indicated by Binder’s poster, electricity stirred incredible fears. Below the image of the man in blue, Binder presented detailed instructions on how to change a light bulb safely. "Changing a light bulb is totally ubiquitous today, but back then it was so little understood, it was perilous," Abess says.

Fear of electrocution was widespread as electric power transmission lines were introduced in the late 1800s, according to Ronald Kline, professor of the history of technology at Cornell University. In the 1880s, residents of New York City panicked when electric wires were installed, and high-profile electrocutions caused a major public outcry. When a maintenance worker was electrocuted, a New York Times article read, "The man appeared to be all on fire. Blue flames issued from his mouth and nostrils and sparks flew about his feet. There was no movement to the body as it hung in the fatal burning embrace of the wires."

Safety was a huge concern, Kline says, but at the same time urban reformers believed that electricity would bring about a new utopian society: electric manufacturing would improve working conditions, mass-transit powered by electricity would reduce urban crowding, and electric streetlights would reduce crime. "Electricity was a symbol of modernity," Kline says.

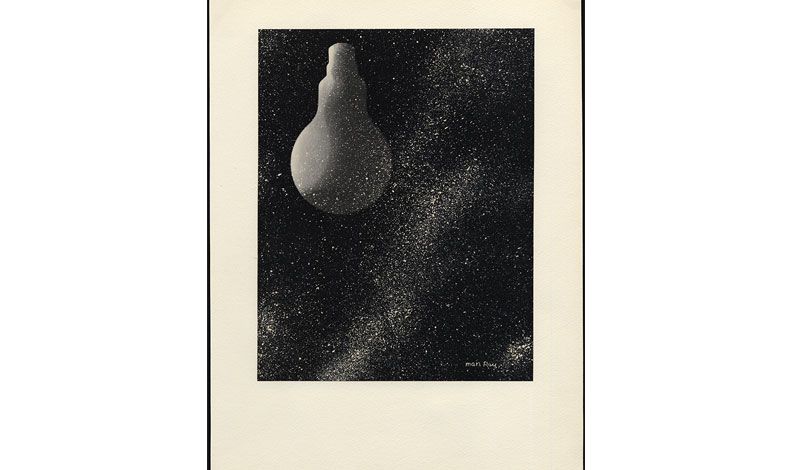

Decades later, in 1931, Man Ray used electricity and not a camera to create his photogram "Élecricité," a subtle, soothing image of a single light bulb and diffuse dots of light in a pattern that resembles the Milky Way. Working off a commission by a Parisian electric company to encourage the use of domestic electricity, Ray created the image with only light-sensitive paper and an electric light source.

The titular “margin of error” comes through even more dramatically in the exhibit’s discussion of mass-casualty accidents, such as the 1937 crash of the Hindenburg. Film footage of the disaster runs alongside a poster created in that same year that captures the beauty and thrill of air travel. Transatlantic flights such as Charles Lindbergh's 1927 solo were considered heroic. But accidents like the Hindenburg crash, which killed 36 people and essentially ended the short reign of travel-by-zeppelin, reminded the public of the inherent danger in what was otherwise a compelling technology.

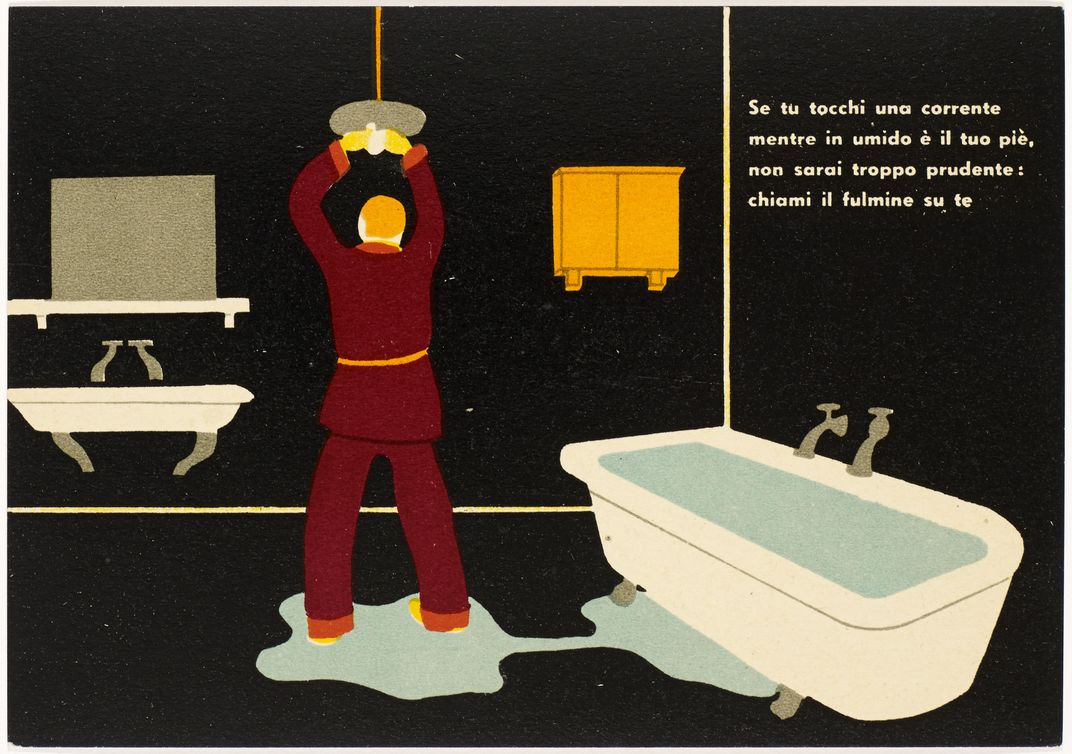

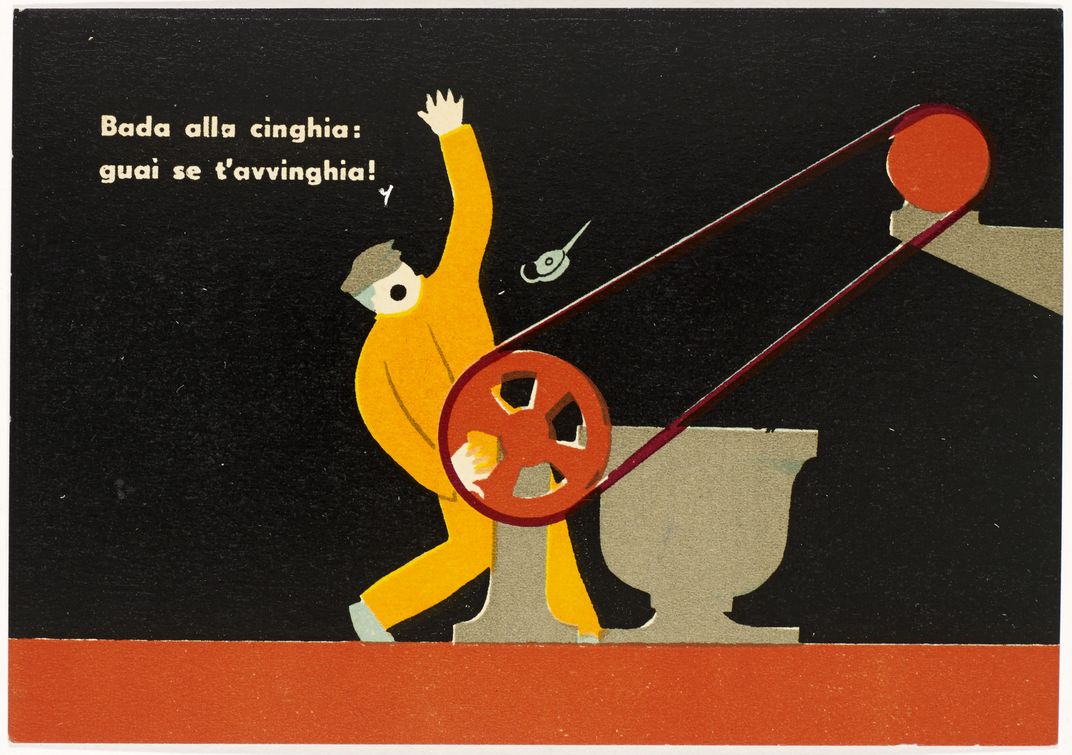

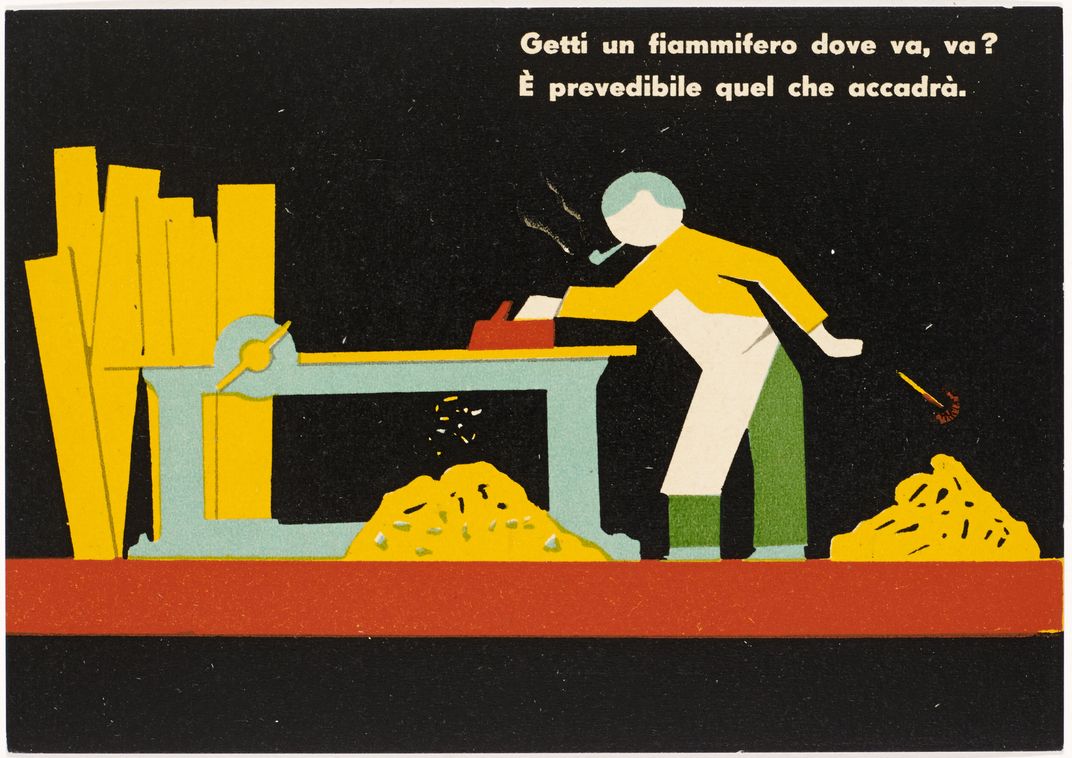

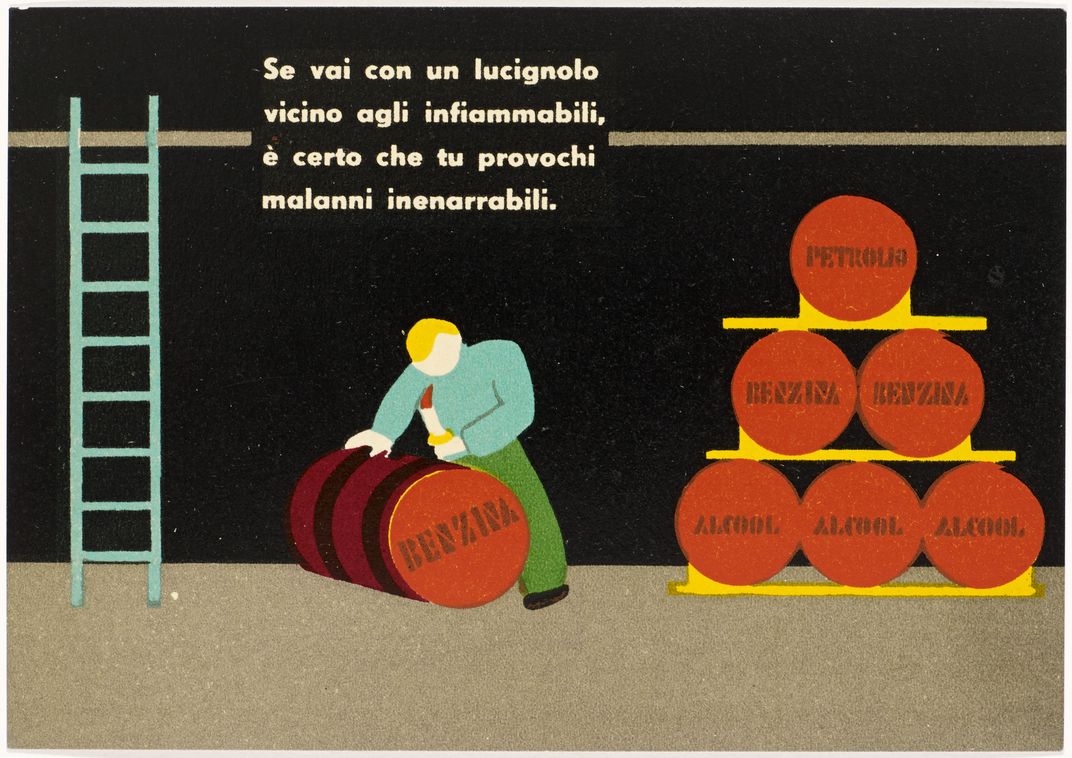

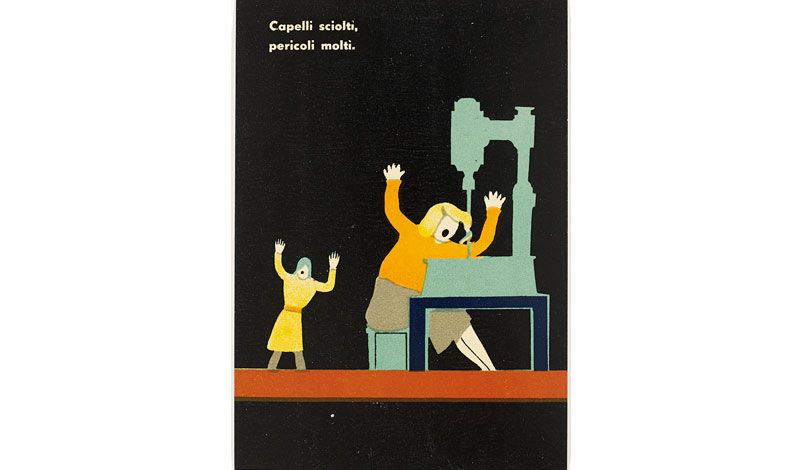

The industrial workplace was no exception to the perilous balance of making life easier and having a life at all. In a series of Italian postcards from the late 1930s, cartoon figures in richly saturated colors slip on an oil slick ("oil on the track, hospital in sight") and get their hands and hair caught in machines ("loose hair, many dangers"). The text is written in rhyming couplets. The images are amusing, and the childish aesthetic is no mistake. "It's the Fascist model of work safety," Abess says. "The state was a parent taking people under its wing."

Italian artist Alberto Helios Gagliardo used the classic subject of the pièta (the Virgin Mary cradling Jesus’ dead body) to depict an accident in Genoa's port, where two workers take the place of Mary and Jesus. The artists used the historic Christian image, favored by Michelangelo, to draw attention to the plight of workers who put themselves in danger and sometimes even sacrificed their lives for the sake of industry. Abess says, "The piece is a confrontation about the risks to make the world as we know it," he adds.

Such images call attention to the fallibility of human engineering, yet there's an undeniable appeal, even beauty, in images of destruction and humiliation. At the 1910 World’s Fair in Brussels, a fire broke out, destroying the British pavilion. Artist Gordon Mitchell Forsyth recreated this scene with a vase that, surprisingly, isn’t despairing, but hopeful: two female figures—Britannia, representing Britain, and a muse of the arts, appear facing each other and touching hands, with flames swirling around them.

"Fire was not supposed to happen at a fair about the glory and achievements of construction," Abess observes, "yet the artist seems to say that from these ashes, art will emerged renewed. Fire is not only a source of destruction, but also a source of renewal."

The theme of hopes and fears springing from innovation is as relevant today as ever: Catastrophes, particularly those not at the hands of terrorists, are common, as evidenced by the recent train derailment in Strasbourg, France, the Amtrak derailment in May, the massive Toyota recall of shrapnel-shooting airbag inflators and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Artists have taken inspiration from such disasters: the eco artists HeHe recreated the Deepwater Horizon spill in miniature; playwrights Patrick Daniels, Robert Berger and Irving Gregory used transcripts from real-life plane crashes to write their play and documentary, Charlie Victor Romeo.

According to Kline, who also teaches engineering ethics, engineers are constantly taking into account the possibility of accidents and building in safety precautions, yet, he says, "technologies fail all the time." Books such as Charles Perrow's Normal Accidents suggest that the system complexity in recent feats of engineering, such as Chernobyl, make mistakes inevitable. Disasters often lead to regulation, but it's impossible for governments to regulate technologies before they are widely understood, Kline says.

Accidents "rattle our faith in things like air and rail travel, things that are commonplace now," Abess says. "The hazards endure. And perhaps they shock us even more, because they are engrained in our culture at this point, so we aren't really considering the risks."