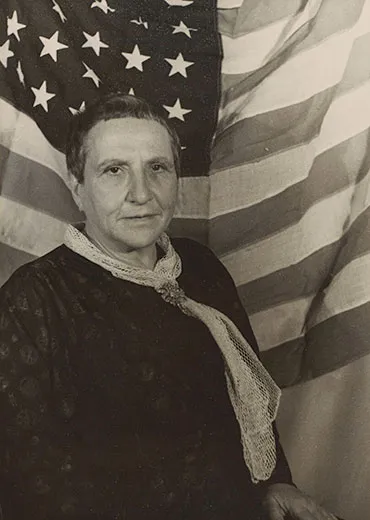

When Gertrude Stein Toured America

A 1934 barnstorming visit to her native country transformed Stein from a noteworthy but rarely glimpsed author into a national celebrity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Gertrude-Stein-in-Bilignin-631.jpg)

When people envision the life and times of Gertrude Stein, it is often in the context of 1920s Paris. Her home at 27 rue de Fleurus was a fabulously bohemian outpost, where she, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and writers, including Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, discussed the merits of art. It was the type of salon that makes writers, artists and historians swoon, “If only I were a fly on the wall.” Perhaps that is why Woody Allen transports his time-traveling character there in his latest film, Midnight in Paris. Gil, a modern-day Hollywood screenwriter portrayed by Owen Wilson, asks Stein (with Kathy Bates in the role) to read his fledgling novel.

The story of the writer’s “salon years” is a familiar one, after all. Stein popularized that interlude in her most successful book, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. But it is entirely fresh stories, as relayed by Wanda M. Corn, a leading authority on Stein, that we encounter in the Stanford art historian’s “Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories,” an exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery on view through January 22.

One of the five threads, or chapters, of Stein’s life featured in the show is her triumphant return to America for a six-month lecture tour in 1934 and ’35. Crisscrossing the country for 191 days, she gave 74 lectures in 37 cities in 23 states. The visit, highly publicized at the time, is little-known now, even though, as Corn asserts, “It is the trip that creates her solid, American celebrity.”

Momentum Builds

During the 1920s and ’30s, Stein’s friends proposed that she visit the United States, suggesting that the journey might allow her to gain an American audience for her writing. Stein had departed California (after years of living outside of Pittsburgh, Baltimore and elsewhere in the country) for France in 1903 at age 27 and hadn’t returned in nearly three decades. “I used to say that I would not go to America until I was a real lion a real celebrity at that time of course I did not really think I was going to be one,” Stein would later write in Everybody’s Autobiography.

For years, publishing houses regarded Stein’s writing style, replete with repetition and little punctuation (think: “rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”), as incomprehensible. But in 1933, she at last achieved the mass appeal she desired when she used a clearer, more direct voice—what she’d later call her “audience voice”—in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. In the States, in four summer issues, the Atlantic Monthly excerpted the best seller, a fictive memoir supposedly written from the perspective of Stein’s partner, Alice. In the winter of 1934, Stein delivered another success—the libretto to American composer Virgil Thomson’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts, which premiered in Hartford, Connecticut, and made a six-week run on Broadway.

“People were buzzing about who she was,” says Corn. Vanity Fair even published a photograph of Stein on its letters page with a plea: “Please, Miss Stein and Miss Toklas, don’t disappoint us: we do be expecting you!”

Arriving in New York

Stein and Toklas disembarked from the S.S. Champlain in New York City on October 24, 1934. When her ocean liner docked, the writer was thronged by a group of curious reporters eager for a firsthand look at the author. “She might have been a name prior to her coming on this trip, but it was a name without substance, because very few people had actually seen her,” says Corn. Front-page articles carried by nearly every newspaper in New York City described her stocky stature and eccentric accoutrements—masculine shoes and a Robin Hoodesque hat.

Though journalists may not have held many preconceived notions about her appearance and demeanor, “What they did know is that she was a very difficult writer,” says Corn. “So they were pleasantly surprised when she arrived and talked in sentences and was straightforward, witty and laughed a lot.” Bennett Cerf, president of Random House, who would later become Stein’s publisher, said she spoke “as plain as a banker.”

When asked why she didn’t speak as she wrote, she said, “Oh, but I do. After all it’s all learning how to read it…. I have not invented any device, any style, but write in the style that is me.” The question followed her throughout her tour. On another occasion she replied, “If you invited Keats to dinner and asked him a question, you wouldn’t expect him to reply with the Ode to a Nightingale, now would you?”

On the Lecture Circuit

Stein was anxious about how she might come across on a lecture tour. She had given only a few speeches, and the last thing she wanted was to be paraded around like a “freak,” as she put it. To assuage her fears, Stein laid some ground rules. At each college, university or museum, with a few exceptions, she would deliver one of six prepared lectures to an audience strictly capped at 500. At her very first lecture, attended by members of the Museum of Modern Art, and routinely thereafter, she entered the stage without introduction and read from her notes, delivered in the same style as her confounding prose. Then, she opened the floor to questions.

Stein’s audiences, by and large, did not understand her lectures. Shortly into her tour, psychiatrists speculated that Stein suffered from palilalia, a speech disorder that causes patients to stutter over words or phrases. “Whether it was Picasso or Matisse or Van Gogh, people said that Modernism [a movement that Stein was very much a part of] was the art of the insane,” says Corn. “It is a very common reductionism that you find running throughout modern arts and letters.” But talk of the putative diagnosis quickly fizzled.

Stein engaged her audience with her personality and the musicality of her language. “Even if people couldn’t follow her, she was so earnest and sincere,” says Corn. “People loved listening to her,” especially during her more candid question-and- answer sessions. According to Corn, Americans “welcomed home the prodigal daughter.” Or grandmother—the 60-year-old was charming.

Media Frenzy and Other Diversions

Within 24 hours of her arrival in New York Harbor, Stein was promoted “from curiosity to celebrity,” according to W.G. Rogers, a journalist and friend of Stein’s. En route to the hotel where she would stay her first night, she saw the message, “Gertrude Stein has Arrived” flashing across an electric sign in Times Square. Soon enough, she was recognized by passers-by on the streets.

In terms of an itinerary, says Corn, “She really didn’t have it sketched out very thoroughly other than a couple of dates on the East Coast. But once she began to talk and the press began to report on her, invitations flowed.” She visited Madison, Wisconsin, and Baltimore; Houston and Charleston, South Carolina; Minneapolis and Birmingham, Alabama. “I was tremendously interested in each state I wish well I wish I could know everything about each one,” wrote Stein.

Wherever Stein went, says Corn, “People kind of dreamed up things that they thought would amuse her or be interesting to her.” After a dinner party at the University of Chicago, two police officers from the city’s homicide department took Stein and Toklas for a ride around the city in a squad car. American publisher Alfred Harcourt invited them to a Yale-Dartmouth football game. At the University of Virginia, Stein was given keys to the room where Edgar Allan Poe stayed for a semester. She had tea with Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House. In New Orleans, writer Sherwood Anderson took her to see the Mississippi River. And, at a party in Beverly Hills, she discussed the future of cinema with Charlie Chaplin.

Media coverage followed Stein’s every move along her tour. “No writer for years has been so widely discussed, so much caricatured, so passionately championed,” declared the Chicago Daily Tribune months after she returned to Paris.

Stein’s 1937 book, Everybody’s Autobiography, is filled with observations from the journey—what she liked and what she found unusual. In New England, she decided that Americans drove more slowly than the French. Heading to Chicago in November 1934 for a performance of Four Saints in Three Acts, she compared the view of the Midwest from the airplane window to a cubist painting. It was her first time flying, and she became a real fan. “I liked going over the Salt Lake region the best, it was like going over the bottom of the ocean without any water in it,” she wrote.

The Mississippi River was not as mighty as Mark Twain made it out to be, Stein thought. But she loved clapboard houses. “The wooden houses of America excited me as nothing else in America excited me,” she wrote. And she had a love-hate relationship with drugstores. “One of the few things really dirty in America are the drugstores but the people in them sitting up and eating and drinking milk and coffee that part of the drugstores was clean that fascinated me,” said Stein. “I never had enough of going into them.” When it came to American food, she thought it was too moist. She did, however, have a fondness for oysters and honeydew melon.

A Successful Trip

On May 4, 1935, Stein left America to sail back to France, having successfully concluded an agreement with Random House to publish just about anything she wrote. From then on, she also had an easier time placing her work in magazines. And yet, it is often said that Stein remains one of the most well-known, yet least-read of writers. “People aren’t going to pick up Stein’s work and make it their bedtime reading,” says Corn. “It’s not easy stuff. Modernism asks viewers and readers to be patient and to work at it.”

But by coming to the United States, Stein certainly cleared up some of the mystique that surrounded the modern arts. According to Corn, at a time when few Modern writers and artists made lecture tours, Stein acted as an ambassador of the Modernist movement. Even though her writing was difficult to digest, by force of her personality and sociability, Stein convinced Americans that the Modernist movement was worthwhile and important. “She put a face on Modernism that people liked,” says Corn. “She made Modernism human.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)