When Hollywood Glamour Was Sold at the Local Department Store

During the 1930s, the world’s most fashionable looks came not from Paris, but from La-La Land

:focal(799x323:800x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/0b/950bc417-6ec4-4779-ba34-8921bfb4888d/image1_1.jpeg)

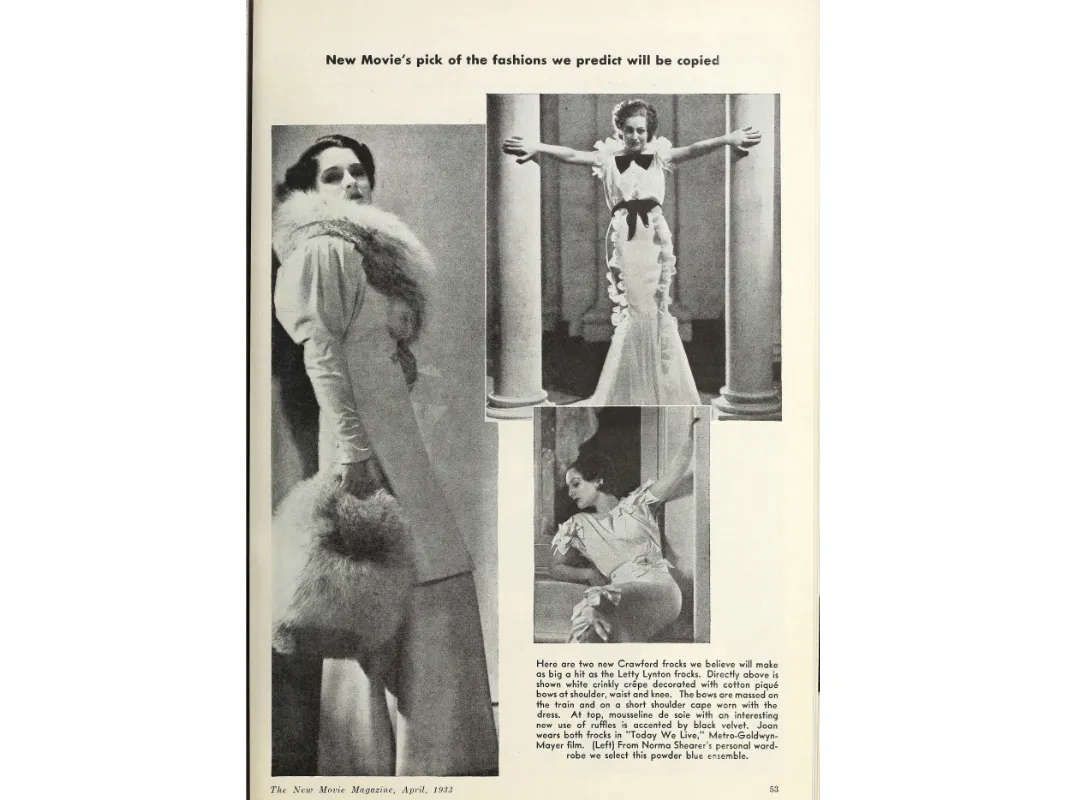

If a woman was in search of an evening gown in 1932, there’s a good chance she considered a particular dress. The floor-length, white organdy showstopper had voluminous pom-pom sleeves with a flouncy, ruffled hem, and was the “it” dress for years to come, sending shockwaves through the fashion world. Inspired by a look worn by movie star Joan Crawford in MGM’s smash-hit Letty Lynton, the gown was the brainchild of costume designer Adrian Greenberg. Its silhouette was so unprecedented that it inspired women to flock to department stores like Macy’s for one of their own.

But what seemed like a fashion fad was really a harbinger of things to come. Though it’s not clear exactly how many Letty Lynton gowns were manufactured and sold, the look was so popular that it has since gained an almost mythical status in the world of costume design and cinema-inspired fashion. That single gown marked a moment in American fashion—one in which costume designers in Hollywood, not couture houses in Paris, started telling American women what to wear. It was the beginning of an era of film-inspired apparel that brought silver-screen looks into the closets of ordinary women.

It took 21 years from the time of the first Academy Awards for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to honor costume design, even though film costumes have captivated audiences ever since the first movies were screened. What few realize, though, is that costume design had a major impact on the global fashion industry.

The early 1930s, during the Great Depression, were Hollywood’s Golden Age and movies offered an exhilarating and accessible form of escape. As film captured America’s collective imagination, what was worn on screen became sensationalized. A new market emerged—and with it, a whole wardrobe's worth of ways to develop and sell products inspired by cinema costumes.

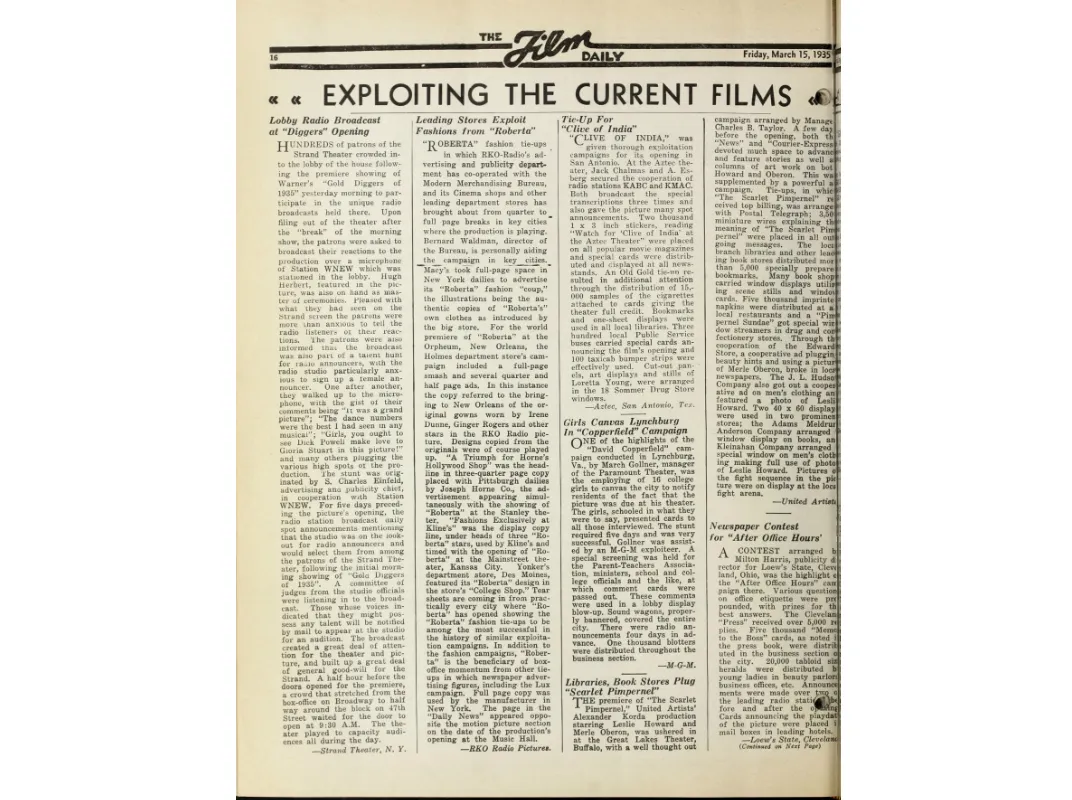

The race was on to capitalize on this new, largely female, consumer group. Heading up the effort were film studios including Paramount, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox and RKO. Since studios had creative control over every aspect of film production and distribution—from directors to actors to costume design—they pioneered new ways to publicize themselves, turning their lucrative movies into even more commercial gold.

Cinema-styled fashion provided more than just an element of intrigue and a clothing choice that differed from what was regularly sold in shops. It all came down to the magic of movies: the fantasy introduced through films’ various plotlines, eras and settings entered people’s homes through their personal wardrobes. These commercial adaptations (sometimes knockoffs, sometimes officially licensed) were sold to a mass market of moviegoers. Manufactured at a low cost with less tailoring and cheaper fabrics, the dresses were sold at an affordable retail price.

One of the first such endeavors came from Hollywood Fashion Associates, a group of fashion manufacturers and wholesalers who got the copyrights to popular Hollywood styles and sold them in exclusive stores in Los Angeles in the late 1920s. Similarly, in 1928, The Country Club Manufacturing Company relied on proprietary styles modeled by recognizable film stars to entice buyers.

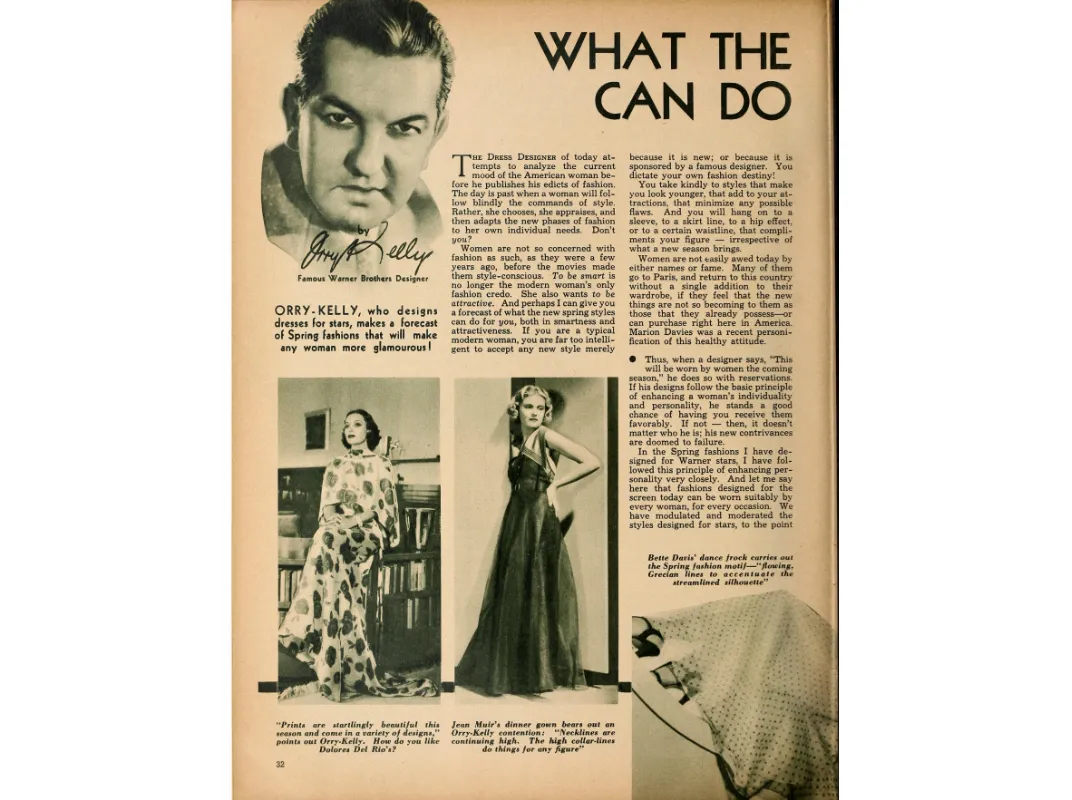

Fashionable Americans had been taking their cues from French haute couture designers like Coco Chanel, Paul Poiret, Jeanne Lanvin and Madeleine Vionnet for years. These looks were of course reflected in glamorous Hollywood productions, but with this new merchandising brainchild, movie studios could capitalize on their own in-house designers instead. “The studios were determined never again to be at the mercy of a small group of French designers," wrote Edith Head, herself one of Hollywood's most famous costumers. "If stars were hot on the social circuit, studio designers were asked to fashion personal wardrobes for them too."

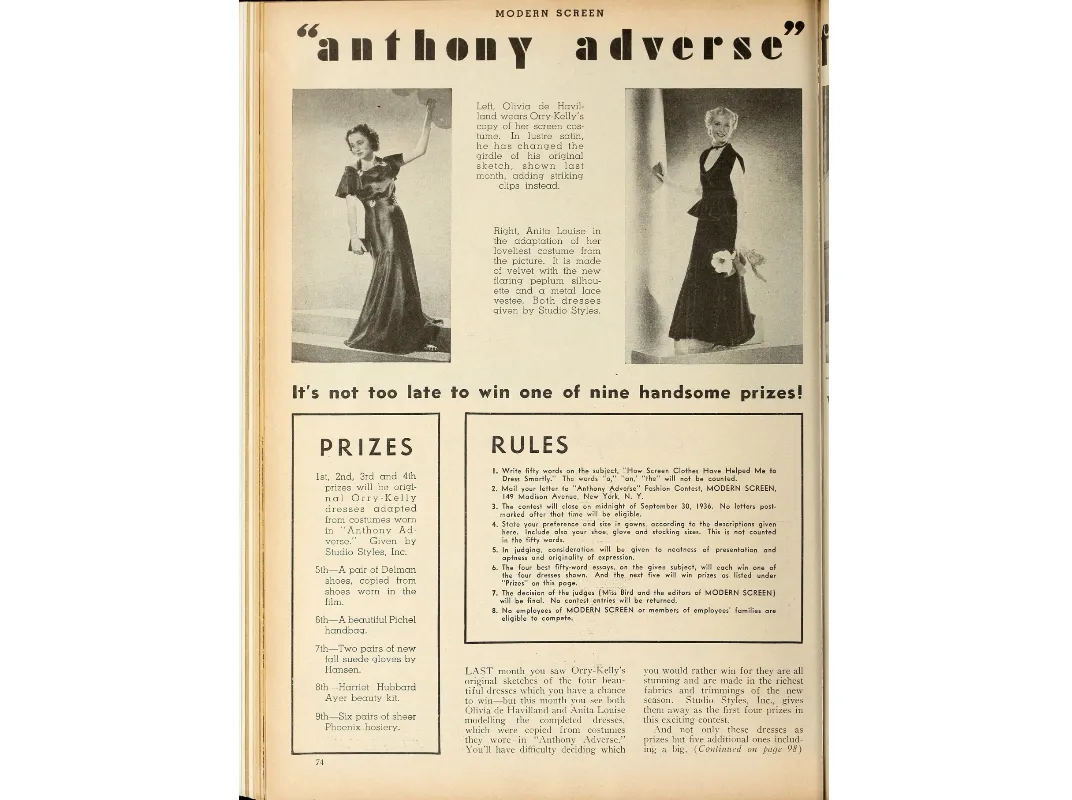

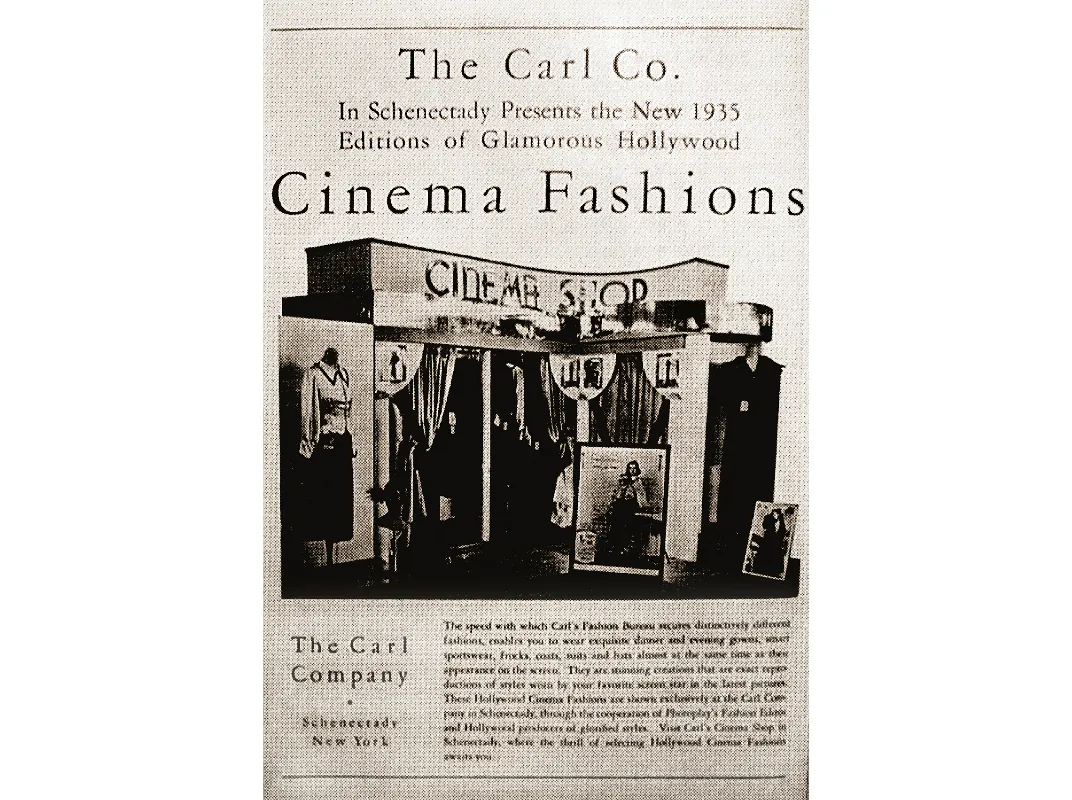

Studios partnered with stores nationwide, producing themed shops with names such as Warner Brothers Studio Styles, Hollywood Fashions and Macy’s Cinema Fashion Shops. They worked with popular magazines to promote their movies as the place to discover fashionable trends.

Studios and retailers publicized the new looks alongside the movie release in fan publications similar to tabloids, including Hollywood Picture Play, Mirror Mirror, and Shadow Play, among others. Esteemed fashion magazines like Vogue also included advertisements for cinema fashion. This outlet turned costume designers into trendsetters. Often these magazines showcased or simply mentioned the contracted studio stars, as it had become apparent that they had a major influence on consumer behavior. In Crawford films like Letty Lynton, writes historian Howard Gutner, the focus on fashion “would become overwhelming, to the point where almost everything in films, including the direction, would take a backseat.”

In 1930, Samuel Goldwyn of MGM took a reverse route by bringing Coco Chanel, one of the world’s most famous designers, to the U.S. to design costumes for his films in a short-lived collaboration. In the same year, Macy’s became the first department store to carry film-inspired fashion, selling evening to casual wear at price points in today’s moderate-to-better fashion range of $200 to $500.

The mainstream fashion industry leveraged formal couture showcases and print publications to spread trends. So did film fashions. Cinema-inspired clothing coincided with film debuts rather than seasonal fashion shows. Marketing in trade publications and on the radio created a sense of timely excitement. Fans could buy a ticket to see the desirable looks, or go to the shop to catch them before they disappeared.

Studios led the way in fashion trends, too, sharing their plans for upcoming films, as early as a year in advance, with Bernard Waldman’s Modern Merchandising Bureau (MMB), a large-scale clothing producer. The result was that when a film premiered, the new fashions would, too—and in turn, the apparel served as an ad for the movie and its studio.

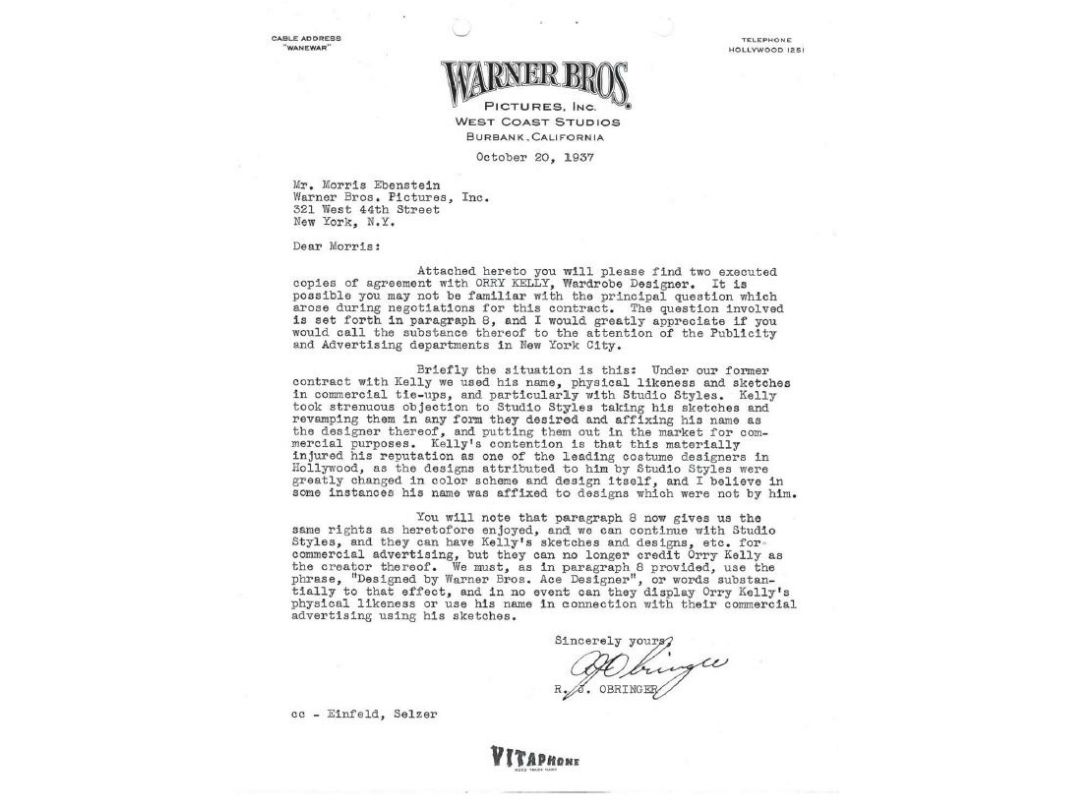

Now, women of all walks of life and in all parts of the country could access cutting-edge fashion without traveling to Paris. But Waldman wasn’t done yet. He franchised more than 400 Cinema Fashion Shops nationwide and another 1,400 stores sold star-endorsed styles. He had competition, though, from Warner Brothers’ Studio Styles. Established in 1934, this highly lucrative product line featured licensed designs inspired by the studio’s leading costume designers. When not featuring actresses in promotions, Warner Brothers publicized its star designer, Orry-Kelly, making him a sought-after crossover costume to fashion designer—similar to Adrian Greenberg.

Adrian—now famous enough to be known by his first name alone—had designed costumes for stars like Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo and Norma Shearer. He got in on the licensing action, too. Macy’s created a line based on Adrian’s costumes for MGM’s 17th-century drama Queen Christina (1933) starring Garbo. Eventually, he used his success to launch a fashion career, leaving Hollywood to start his own fashion house in the 1940s.

But, just as fashion trends come and go, so too did the commercialization of film-inspired fashion. Eventually, the power of the studio system waned, weakening their centralized marketing machine. And as the Golden Age of Hollywood faded, the movie industry was no longer seen as fashion-forward. In 1947, Christian Dior’s “new look” redefined the silhouette for modern women—and put French designers at the forefront of women’s fashion once more.

What became of the dresses that dictated a major shift in the entire fashion industry? Regretfully, early Hollywood costumes weren’t valued, preserved and exhibited as carefully as they are today. Over the years, costumes were rented out, refashioned, or simply lost. Similarly, relatively little evidence of cinema-inspired fashion survives. Through insider correspondence and 1930s fan magazines, we can see what was produced and sold in stores across the United States.

Many of the dresses that captured the American imagination through a bit of movie magic are treasures, stowed away in homes across the country. While not originals, retail replicas serve as an invaluable fashion reference, helping fill the gap left by original costumes worn in beloved films before they were deemed of sufficient value to collect.