Where Are the Great Revolutionary War Films?

You’d think the 4th of July would inspire filmmakers to great works, but they have been unable to recreate the events that led to the founding of America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120703121042Revolution-pacino-thumb.jpg)

As we celebrate this Independence Day, some might wonder why the Revolutionary War has been shortchanged by filmmakers. Other countries have made an industry out of their past. Shakespeare’s historical plays are filmed repeatedly in Great Britain, where filmmakers can borrow from old English epics like Beowulf and contemporary plays like A Man for All Seasons. Even potboilers like the Shakespeare conspiracy theory Anonymous, or The Libertine, with Johnny Depp as the second Earl of Rochester, are awash in details—costumes, weaponry, architecture—that bring their times to life.

Films like Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai or Kagemusha do the same for earlier Japanese culture. The Hong Kong film industry would not exist without its films and television shows set in the past, and mainland Chinese filmmakers often use period films to skirt present-day censorship restrictions.

Mel Gibson as The Patriot.

In the golden age of the studio system, Western films provided more income and profit than many A-budget titles. And the Civil War has been the backdrop of some of the industry’s biggest films, like The Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind. But successful American films set in the Revolutionary period are hard to find. You’d think that filmmakers would jump at the chance to recreate our country’s origins.

Part of the problem is due to our general ignorance of the times. D.W. Griffith released The Birth of the Nation on the 50th anniversary of the end of the Civil War. Some moviegoers could remember the fighting, and many of the props in the film were still in general use. When Westerns first became popular, they were considered contemporary films because they took place in an identifiable present. Many of Gene Autry’s movies are set in a West that features cars and telephones.

Westerns were so popular that an infrastructure grew up around them, from horse wranglers to blacksmiths. Studios hoarded wagons, costumes, guns. Extras who could ride got a reliable income from B-movies.

That never happened for films set in the Revolutionary period. Designers had little experience with costumes and sets from eighteenth century America, and few collections to draw from. Screenwriters had trouble grappling with events and themes of the Revolution. A few incidents stood out: the Boston Tea Party, Paul Revere’s midnight ride, the Minutemen. But how do you condense the Constitutional Congress to a feature-film format?

Still, some filmmakers tried, as you can see below:

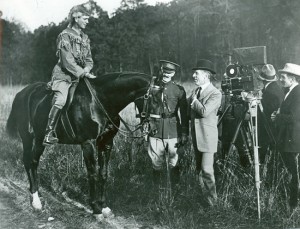

Major Jonathan M. Wainright, Colonel J. Hamilton Hawkins, and D. W. Griffith discuss the cavalry charge scene in America. Courtesy William K. Everson Archive, NYC

America (1924)—The Birth of a Nation made D.W. Griffith one of the world’s most famous filmmakers, but it also put him in the position of trying to top himself. After directing movies big and small, Griffith found himself in financial trouble in the 1920s. When a project with Al Jolson about a mystery writer who dons blackface to solve a crime fell apart, the director turned to America. According to biographer Richard Schickel, the idea for the film came from the Daughters of the American Revolution via Will Hays, a former postmaster and censor for the film industry.

Griffith optioned The Reckoning, a novel by Robert W. Chambers about Indian raids in upstate New York. With the author he concocted a story that included Revere, the Minutemen, Washington at Valley Forge, and a last-minute rescue of the heroine and her father from an Indian attack. When he was finished, America was his longest film, although when the reviews came in Griffith quickly started cutting it down. Critics compared it unfavorably not only to The Birth of a Nation, but to work from a new generation of filmmakers like Douglas Fairbanks, Ernst Lubitsch, and James Cruze.

1776 (1972)—Turning the second Continental Congress into a Broadway musical may not seem like much of a money-making plan, but songwriter Sherman (“See You in September”) Edwards and librettist Peter Stone managed to parlay this idea into a Tony-winning hit that ran for three years before going on the road.

Edwards and Stone teamed for the film adaptation, directed in 1972 by Peter H. Hunt, who also directed the stage show. Many of the actors repeated their roles on screen, including William Daniels, Ken Howard, John Cullum and Howard Da Silva. The film received generally poor reviews. Vincent Canby at the New York Times complained about the “resolutely unmemorable” music, while Roger Ebert at the Chicago Sun-Times said the movie was an “insult.”

What strikes me, apart from the garish lighting scheme and phony settings, is its relentlessly optimistic, upbeat tone, even when delegates are arguing over slavery and other demanding issues. When the play opened many liberals thought it was commenting indirectly but favorably on the Vietnam War. On the advice of President Richard Nixon, producer Jack Warner had the song “Cool, Cool Considerate Men” cut from the film because it presented the delegates as elitists trying to protect their wealth.

Revolution (1985)—Not to be confused with the 1968 hippie epic with music by Mother Earth and the Steve Miller Band, this 1985 film starred Al Pacino as a New Yorker drawn unwillingly into fighting the British in order to protect his son. Blasted by critics on its release, the $28 million film reportedly earned less than $360,000 in the US.

This was the debut feature for director Hugh Hudson, who went on to helm the international smash Chariots of Fire. For the recent DVD and Blu-ray release, Hudson complained that the film was rushed into release before he could finish it. His new director’s cut adds a voice-over from Al Pacino that helps hide some of the production’s bigger flaws, like an inert performance from Nastassja Kinski and a laughable one from Annie Lennox, as well as a plethora of dubious accents.

In “Is Hugh Hudson’s Revolution a neglected masterpiece?” Telegraph writer Tim Robey is willing to give the film a second chance, commenting on Bernard Lutic’s gritty, handheld camerawork and the squalor on display in Assheton Gorton’s production design. But Revolution was so ill-conceived, so poorly written, and so indifferently acted that no amount of tinkering can rescue it. It remains in the words of Time Out London “an inconceivable disaster,” one that nearly destroyed Pacino’s movie career.

The Patriot (2000)—Mel Gibson has made a career out of his persecution complex, playing a martyr in everything from Mad Max to Braveheart. The success of Braveheart, which won a Best Picture Oscar, may have encouraged Gibson to make The Patriot, essentially the same plot with a Revolutionary setting. (With variations, that story engine also drives We Were Soldiers, The Passion of the Christ, Apocalypto, even his remake of Edge of Darkness.)

The Patriot was a big-budget film, with a cast that included rising star Heath Ledger, cinematography by Caleb Deschanel, and careful treatment from the directing and producing team of Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin (Independence Day). Devlin even credited the Smithsonian for adding to the picture’s historical accuracy.

But the script reduced the Revolutionary War to a grudge match between Gibson’s plantation owner and a callous, cruel British colonel played by Jason Isaacs. Of course if the British murdered your son and burned down a church with the congregation inside you’d want to hack them to pieces with a tomahawk.

Northwest Passage (1940)—Yes, it’s the wrong war and the wrong enemy, and King Vidor’s film drops half of Kenneth Roberts’ best-selling novel set in the French and Indian War. But this account of Major Robert Rogers and his rangers is one of Hollywood’s better adventures. MGM spent three years on the project, going through over a dozen writers and a number of directors. Location filming in Idaho involved over 300 Indians from the Nez Perce reservation. By the time it was released in 1940, its budget had doubled.

Most of the action involves a trek by Rogers and his men up Lake George and Lake Champlain, ostensibly to rescue hostages but in reality to massacre an Indian encampment. Vidor and his crew capture the excruciating physical demands of dragging longboats over a mountain range and marching through miles of swamp, and also show the graphic effects of starvation. Spencer Tracy gives a bravura performance as Rogers, and he receives excellent support from Robert Young and Walter Brennan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)