Where Did Jackson Pollock Get His Ideas?

A talented painter who died poor and forgotten may have inspired the influential American artist’s work in ceramics

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120524024008Ross-Braught-Mnemosyne-and-the-Four-Muses-web.jpg)

One of the more surprising and unusual works in the new American Wing of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is an early ceramic bowl by Jackson Pollock, decorated in black and fierce fiery red, which was acquired in 2010 by the museum. The MFA describes the bowl as influenced by El Greco, which is not entirely wrong, since Pollock made pencil copies after paintings by El Greco around this time. But I’d like to propose that it’s possible to pin down its source more precisely. I believe it’s inspired by a work by a now largely forgotten painter of the 1930s, Ross Braught—in fact, based on Braught’s most ambitious painting, a mural in the Kansas City Music Hall. Identifying this source opens up a whole new set of questions and speculations.

Pollock’s interest in ceramics was inspired by the work of his teacher, Thomas Hart Benton, who had discovered during his impoverished years in New York that it was easier to sell decorated ceramics than paintings.

Pollock’s surviving ceramics seem to have been made at two times.He made one group during four successive summers, 1934-1937, while staying on Martha’s Vineyard with Benton and his wife, Rita. The Bentons kept quite a few of these ceramics and eventually donated them to various museums. The others were made in 1939 while Pollock was being treated for alcoholism at the Bloomingdale Hospital. Just two of these pieces survive, but they’re Pollock’s most impressive early ceramics: Flight of Man, the piece now in Boston, which he gave to his psychiatrist, James H. Wall, and The Story of My Life, which he made at the same time and sold to a gentleman named Thomas Dillon in Larchmont, New York. The whereabouts of this last piece are unknown. At the time Pollock made these two pieces, he had just returned from a visit to the Bentons in Kansas City, the only time he visited there.

The Story of My Life contains a series of scenes: an archer shooting an arrow at some horses in the sky; a sleeping woman; a child in fetal position; and a boat sailing on restless seas. Pollock’s biographers, Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, have described it as “an impenetrable allegory”; in fact, its meaning is easy to construe once we recognize its source, an illustrated book, Phaeton, published by Braught in 1939. Phaeton was the son of Apollo and obtained permission from him to drive the chariot of the sun. But since he was unable to control the horses, the chariot plunged down close to earth, scorching the planet. To prevent further destruction, Apollo was forced to shoot his son down from the sky. The two most significant images on Pollock’s bowl, the archer and the sleeping woman are both derived from Braught’s book. The third, the boat on restless seas, relates to paintings that Pollock had made earlier on Martha’s Vineyard, of the boat of Benton’s son, T.P., sailing on Menemsha Pond. Clearly Pollock saw Phaeton’s story as parallel to his own life as an artist. At one moment he was soaring to great heights, at the next crashing to earth.

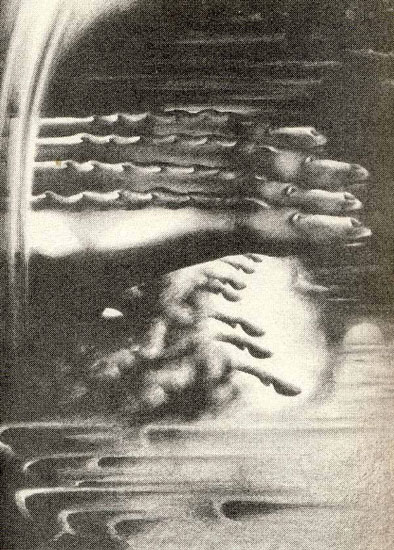

If we accept this source, it’s not surprising to discover that Pollock’s second painted bowl, the one in Boston, was also based on a work by Braught. Its imagery resembles that of the most ambitious painting of Braught’s career, a 27-feet-high mural, Mnemosyne and the Four Muses, which he created for the Kansas City Music Hall. As the title indicates, the swirling composition shows Mnemosyne, or Memory, who was the mother of the muses, and four muses, who are emerging from clouds that float over a landscape of the badlands of South Dakota. Braught also made a painting of the landscape at the bottom, which he titled Tchaikovsky’s Sixth (1936; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). This was the last piece that Tchaikovsky wrote before he died—as some believe, by committing suicide. Perhaps that’s the music we’re meant to imagine when we look at the painting.

To be sure, Pollock didn’t follow his source very closely. What he took was Braught’s general formula: a central floating figure with outstretched arms, suffused with mysterious light, surrounded by other figures and cloud-like forms that fill the surrounding space. I suspect that close study would reveal prototypes for many of Pollock’s figures. For example, the over-scaled figure on the right-hand side loosely relates to a painting he had made shortly before, Naked Man with Knife (c. 1938; Tate, London). Compared with Braught’s design, Pollock’s is somewhat crude, with figures of differing scales, which often fill their spaces somewhat awkwardly. But it was precisely Pollock’s departures from traditional ideas of correct proportion or well-resolved design that led to his wildly expressive later work.

Who was Ross Braught? Why was Pollock interested in him?

A lithograph by Braught of horses from the sun from the Phaeton myth. Braught's work had a mystical, visionary cast that would have appealed to Pollock. Image from Phaeton.

Braught just preceded Benton as the head of the painting department at the Kansas City Art Institute. An eccentric figure, he bore a striking resemblance to Boris Karloff. He generally wore a black cape, and sometimes brought a skeleton with him on the streetcar, so that he could draw it at home. His work had a mystical, visionary cast. It clearly held strong appeal for Pollock at a time when he was going through intense emotional turmoil, and was also attempting to move beyond the influence of Benton.

Pollock surely met Braught in 1939, just before he made the bowl, when he visited the Bentons in Kansas City in January of that year. At the time, Pollock also socialized with Ted Wahl, the printer of Braught’s lithographs for Phaeton. While not well known today, Braught was getting a good deal of press coverage at the time, both for his painting for the Kansas City Music Hall, which was praised in Art Digest, and for his lithograph Mako Sica, which received a first prize at the Mid-Western Exhibit at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1935 (and became the subject of articles questioning its merit shortly afterward in the Print Collector’s Quarterly).

Sadly, Braught’s career faded at this point, perhaps in part because he was so unworldly and impractical. After leaving Kansas City in 1936, he lived for most of the next decade in the tropics, where he made drawings and paintings of dense jungle foliage. From 1946 to 1962, he returned to teach at the Kansas City Art Institute, but in 1962, when Abstract Expressionism was in vogue, he was fired because his style was considered too old-fashioned. The figure who had inspired Jackson Pollock was no longer good enough to matter. Braught spent the last 20 years of his life living in extreme poverty in Philadelphia, no one knows exactly where.

There’s been only one exhibition of Braught’s work since his death, a show at Hirschl & Adler Galleries in New York in March-April 2000, accompanied by an excellent, hard-to-find catalog written by David Cleveland. Both the Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia have paintings by him in their collections.

For two reasons, Pollock’s interest in Braught is worth noting. One is that when we identify Pollock’s sources, his creative process is illuminated and we can see the step-by-step process by which he moved toward being an original artist. In some ways it’s a bit deflating. Pollock clearly started off as a copyist. Nonetheless, while Pollock’s bowl is in some ways quite derivative, you can already sense his emerging artistic personality.

Second, perhaps Pollock’s interest in Braught will encourage a modest revival of interest in Braught. Braught’s output is so scarce that he’ll surely never be regarded as a major figure, but it is well worth a visit to see his work at the Kansas City Music Hall, one of the greatest Art Deco interiors anywhere, which also houses some good paintings made around the same time by Walter Bailley.

Braught’s Mnemosyne and the Four Muses is surely one of the weirdest and most unusual wall paintings in this country. As you stand in front of it, you wonder why Pollock chose it as a model for his own work and what to make of his artistic taste. Was he misguided? Or right to be inspired by an artist who’s now so thoroughly forgotten?

There’s a copy of Ross Braught’s book Phaeton in the library of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Some early ceramics by Jackson Pollock reside in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and in a few private hands.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)