Which is the Fairest Snow White of Them All?

With two big-screen adaptations about to arrive, here are earlier versions of the fairy tale that you might want to see

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120307114113Snow_Roberts-thumb.jpg)

For 60 years, Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has been the gold standard for how to film a fairy tale. It was the most successful musical of the 1930s, out-performing Fred Astaire, Judy Garland, and Show Boat. It popularized such best-selling songs as “Whistle While You Work” and “Someday My Prince Will Come.” And it was the first in a remarkable run of animation classics from the Disney studio.

Two new live-action movies will look to unseat Disney’s version of Snow White in the coming weeks. First up, and opening on March 30: Mirror Mirror, directed by Tarsem Singh and starring Lily Collins as Snow White and Julia Roberts as the evil Queen. It will be followed on June 1 by Snow White & the Huntsman, starring Kristen Stewart and Charlize Theron.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarves was a huge risk for Disney, but also the only direction he could take his studio. Disney’s cartoon shorts helped introduce technological innovations like sound and color to the moviegoing public, and characters like Mickey Mouse became famous the world over. But Walt and his brother Roy could not figure out a way to make money from shorts—the Oscar-winning Three Little Pigs grossed $64,000, a lot at the time, but it cost $60,000 to make. Like Charlie Chaplin before them, the Disneys needed to commit to feature films to prosper.

Disney picked the Grimm Brothers’ “Snow White” because of a film he saw as a newsboy in Kansas City. Directed by J. Searle Dawley and starring Marguerite Clark, the 1916 Snow White was distributed by Paramount. As a star, Clark rivaled Mary Pickford in popularity. She had appeared on stage in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, written by Winthrop Ames and produced in 1912. By that time Snow White had already reached the screen several times. Filmmakers were no doubt inspired by a special-effects laden version of Cinderella released by Georges Méliès in 1899 that was a favorite Christmas attraction in theaters for years.

A popular genre in early cinema, fairy tale films included titles like Edwin S. Porter’s Jack and the Beanstalk (1902), which took six weeks to film; a French version of Sleeping Beauty (1903); Dorothy’s Dream (1903), a British film by G.A. Smith; and William Selig’s Pied Piper of Hamelin (1903).

Ames borrowed from the Cinderella story for his script, but both the play and film feature many of the plot elements from the Grimm Brothers tale “Little Snow White.” Although Snow White the film has its dated elements, director Dawley elicits a charming performance from Clark, who was in her 30s at the time, and the production has a fair share of menace, black humor, and pageantry. The film is included on the first Treasures from American Film Archives set from the National Film Preservation Foundation.

Young Walt Disney attended a version in which viewers were surrounded on four sides by screens that filled in the entire field of vision. “My impression of the picture has stayed with me through the years and I know it played a big part in selecting Snow White for my first feature production,” he wrote to Frank Newman, an old boss, in 1938.

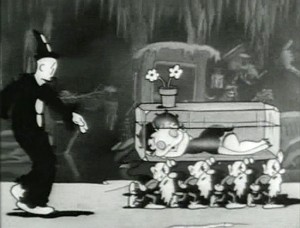

Disney was working on his Snow White project as early as 1933, when he bought the screen rights to the Ames play. That same year the Fleischer brothers released Snow-White, a Betty Boop cartoon featuring music by Cab Calloway, who performs “St. James Infirmary Blues.” The short owes little to the Grimm Brothers, but remains one of the high points of animation for its intricate surrealism and hot jazz.

The Fleischers, Max and Dave, had been making films for almost twenty years when they started on Snow-White. In 1917, Max patented the rotoscope, which allowed animators to trace the outlines of figures—a technique still in use today. He was making animated features in 1923, introduced the famous “follow the bouncing ball” sing-along cartoons the following year, and captivated Depression-era filmgoers with characters like Betty Boop and Popeye.

The pre-Code Betty Boop was a bright, lively, sexy woman, the perfect antidote to bad economic times. Soon after her debut she was selling soap, candy, and toys, as well as working in a comic strip and on a radio show. Snow-White was her 14th starring appearance, and the second of three films she made with Cab Calloway. Her other costars included Bimbo and Ko Ko, to me the eeriest of all cartoon figures.

(For flat-out weirdness, I don’t think anything tops Bimbo’s Initiation, but all the Fleischer brothers’ films have something to recommend them.)

Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs had an enormous impact on Hollywood. Variety called it “a jolt and a challenge to the industry’s creative brains.” The film ran for five weeks in its initial run at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, playing to some 800,000 moviegoers. Although it cost the studio $1.5 million to make, the film grossed $8.5 million in its first run. Its success helped persuade MGM to embark on The Wizard of Oz. The Fleischers, meanwhile, set out to make their own animated feature, Gulliver’s Travels.

It’s too soon to tell what kind of impact Mirror Mirror and Snow White & the Huntsman will make, but they are following some tough acts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)