Pinocchio was breathless. He could see the assassins coming for him, so he ran as fast as his wooden legs would carry him. He reached a house, knocked and screamed for help. The house was silent—and the assassins were nearby. Pinocchio started kicking the door and smashing his head into it.

A little girl with blue hair appeared in the window. Her eyes were closed and arms crossed over her chest. Without moving her lips, and with a voice that seemed otherworldly, she said, “In this house there is no one. Everyone is dead.” Pinocchio’s desperation grew. Screaming, he pleaded with her, “At least you open, please.” The little girl’s lips remained sealed. “I’m dead too,” she said. When Pinocchio asked her what she was doing at the window, the little girl said she was waiting for the coffin to take her away.

The blue-haired girl disappeared, and the window closed without making a sound. Pinocchio started crying, asking the girl for compassion. But it was too late. The assassins caught him and hung him from a big oak tree.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/86/dc/86dcdc03-43de-453e-b891-8e4ff0655f16/giornale_per_i_bambini_pinocchio_collodi_1882.jpg)

Carlo Lorenzini, known as Carlo Collodi, originally published The Adventures of Pinocchio in 1881 in Il Giornale per i bambini, an Italian newspaper for children. When the story ended with Pinocchio hanging from a tree, kids were distraught. The newspaper was flooded with letters from young readers asking Collodi to revive the character.

Several months later, the author agreed. He began the second run of installments with a magical fairy, still in the form of a little girl with blue hair, looking out the window. The fairy (fata in Italian) felt pity for Pinocchio, who was hanging by his neck and being pushed around by the wind, so she called a falcon to save him.

Pinocchio’s audience grew hungry for more. In 1883, Collodi published his installments in a book, which became one of the most translated books in the world, with printed versions in some 300 different languages.

Contrary to public belief, the original story is not about a puppet with an ever-growing nose. In fact, Pinocchio’s nose only grows two times in response to his lying, and not until Collodi’s second run of installments—it just wasn’t central to the tale. It was Disney’s 1940 film that accentuated this character trait, and used it like a visual special effect in those times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b4/38/b438bc7f-458c-4976-bcaa-0e45a659ef4a/gettyimages-1137299683.jpg)

This is why, after reading Collodi's original book—in Tuscan language—to her son, Anna Kraczyna was determined to create a new, more faithful translation of Pinocchio. Growing up a few miles south of Florence in the Tuscan countryside, where the dialect was close to the one spoken in Collodi’s time, Kraczyna was even more aware of the subtleties of the language itself.

“Pinocchio’s message is more complex and multifaceted than people would expect,” says Kraczyna. “It’s actually a story reflecting the dreadful condition of the poor at the time, and a satire displaying many traits of Italians—among many, the constant preoccupation with bella figura [to make a good impression on others]. The central idea to the original story is that if you don’t get an education, you can’t acquire your humanity and will forever remain a puppet—other people will pull your strings. Or even worse—you will be a donkey, live the life of a donkey and maybe even die the death of a donkey.” In Italian, to be a donkey, or asino, means to either not be good in school or to work to the point of exhaustion.

Collodi’s tale was scarier and darker than Disney’s version, as many frightening misadventures happen, adds Kraczyna. “But you never forget that he is writing for children, because he has a way of cheering up his little readers after the terrifying episodes,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6c/7b/6c7bea9b-77bd-4ba6-8ce4-7131ed5d8df5/img_1255.jpg)

Kraczyna, who has taught Italian language, literature and culture at the Florence campuses of Stanford University and Sarah Lawrence College, embarked on a journey to learn more about the true story behind the wooden puppet in 2017. She recruited John Hooper, The Economist’s Italy and Vatican correspondent, on her search. Together, they co-wrote a new annotated translation of The Adventures of Pinocchio, which was published in September 2021.

During her research, Kraczyna realized that many of the characters and settings in Pinocchio were inspired by real people and places in the author’s life. One of them in particular caught her attention: the Blue-Haired Fairy.

Collodi would spend a lot of time with his brother, Paolo Lorenzini, in Villa Il Bel Riposo, a place Paolo would rent in Castello, a town about six miles outside of Florence. The small town, full of large, decorated villas, was a place where wealthy families in Florence, such as the Medici, would go to escape the summer heat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/f5/4ff57916-833d-4d6f-9917-f7c392023d64/img_0963.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b0/9e/b09efa51-e497-4fa8-a914-bd9707b410bf/img_1025.jpg)

While living in Castello, Collodi, his mother, Paolo and Paolo’s wife grew fond of Giovanna Ragionieri, the daughter of the villa’s gardener. The child, who first met the Lorenzinis when she was five or six years old, often ran around their garden and house, and became very close to the family, as neither of the Lorenzini brothers had children. She would occasionally be invited to their visits to the theater in Florence, or whenever they would fare un giro (go for a ride).

“In a book written by Nicola Rilli titled Pinocchio in Casa Sua, Rilli writes that once, after the Lorenzinis had picked up Giovanna from her house—which was a few hundred meters from their villa—she passed some gas,” Kraczyna says. “Giovanna’s mother said she couldn’t do that in front of the padroni (masters). Feeling ashamed, she hid from them for a long time.” Whenever they would pick her up for a walk, Giovanna pretended that she was sleeping, Kraczyna adds.

Years later, Ragionieri would tell funny stories about the Lorenzinis. In a 1962 article in La Nazione, a Florence-based newspaper, writer G. Gattai recounts a time when Collodi told Ragionieri that if she was a good girl, he would turn her into a Blue-Haired Fairy. She said, “But I don’t have blue hair!” And Collodi replied that it didn’t matter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/ad/c3adcc00-4577-441f-8160-47f8876b6773/cantatopinocchio.jpg)

“When I first saw a photo of Giovanna Ragionieri, even though it was black and white, the blue of her eyes still came out, so you can tell that as a child she must have had incredible blue eyes,” Kraczyna says. “Collodi always made some little transformation of reality, so it didn’t surprise me that he would call her the Blue-Haired Fairy.”

But did Ragionieri really inspire the creation of the fairy? Probably.

In an article published in Il Giornale del Mattino in 1956, author R. Gazzaniga claimed that the Blue-Haired Fairy was inspired by the daughter of Villa Il Bel Riposo’s gardener, mentioning Giovanna Ragionieri by name. When this article came out, one of the leading singers and actors in Italy at the time, Johnny Dorelli, visited Ragionieri. Dorelli had recorded a version of a song titled “Lettera a Pinocchio,” which was composed by Mario Panzeri. As a gift, Dorelli gave a radio to Ragionieri, which he turned on and they sang the song together.

After an article about Dorelli singing with Ragionieri was published in La Nazione in 1962, Ragionieri rose to fame. Many newspapers were interviewing her, wanting to know more about the woman who had inspired Collodi’s fairy. According to Rilli’s Pinocchio in Casa Sua, Ragionieri was born in 1868 in Castello, and she died there in 1962 at the age of 94. Not much is known about the muse, other than that she knew how to read and had a daughter. She is buried in the cemetery at Parrochia di San Michele a Castello.

Years later, the craze continued. In a 2006 interview with Piero Faggi, Ragionieri’s grandson, Faggi mentioned that the Lorenzinis “le volevano molto bene” (were very fond of her), and that she was always free to traverse from her house to Villa Il Bel Riposo.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4b/6a/4b6a33f2-765d-4a6a-8b54-8f647d17e4ad/img_1051-3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/e7/2de7a2e1-3635-46f4-8021-31e7bfd9b690/img_1054.jpg)

Nonetheless, the Lorenzinis’ life was far from tragedy-free. Out of Collodi’s nine siblings, four died when they were infants. One of them, Marianna Seconda, passed away when she was just six years old.

“When the little girl with blue hair at the beginning of Pinocchio says that she is dead, Collodi was probably dwelling upon memories of Marianna Seconda when she died,” Kraczyna says. “The ‘blue hair’ first came into the book as an inspiration from Giovanna Ragionieri—but probably with the echoes of seeing his little dead sister as well.”

Although Marianna Seconda never grew into a woman, the Blue-Haired Fairy did. And throughout Pinocchio, the blue hair is a recurring motif—and not always in the form of a fatina (sweet fairy).

In chapter 24, for instance, Pinocchio goes to the island of the “busy bees,” and looks for someone to give him food, as he was very hungry. When asked to work, he disdainfully refuses. Yet, in the end, a “good little lady” with blue hair passes by and convinces Pinocchio to help her carry some water to her house, in exchange for a nice meal.

In the beginning of chapter 25, when Pinocchio had already recognized her blue hair, the “good little lady” first denies and then admits to being the fatina. When she asks Pinocchio how he realized that it was her, Kraczyna recalls that he says, “It’s because I love you so much.” She replies, “Remember me, you left me when I was a child and now I’m a woman, so much of a woman that I could behave as your mom.” And Pinocchio decides that he will call her his mom.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/8a/f58af7ca-38a0-4784-a35d-92d29a024ecc/gettyimages-855007244.jpg)

Later on in the book, Pinocchio goes to “Playland,” a place where children that refuse to go to school are taken. Here, they play until they become donkeys, and then they are sold. In the case of Pinocchio, he was sold to a circus. During a circus act, he sees the Blue-Haired Fairy in the audience and tries to call her. But all he’s able to do is bray. “It is heartbreaking,” says Kraczyna. Then, after breaking his leg, the now donkey-Pinocchio is sold so that his hide can be used to make a drum. When Pinocchio is being drowned, he starts swimming away. During his escape, a goat—with blue hair—appears on top of a rock in the middle of the sea and tells Pinocchio to hurry to avoid a pescenane (shark).

In this way, the Blue-Haired Fairy keeps appearing, in different forms, throughout the story.

“What's interesting is that she is the figure in the story of Pinocchio that has the most agency,” Kraczyna says. “Collodi was very close to his mother, they lived together for long portions of their lives and with Paolo as well, so if there is someone who really impacted Collodi between his two parents, it was his mother. His father was the one who got indebted, who was unable to provide for the family, while his mother would always be by his side.”

Collodi’s mother, Angiolina Orzali Lorenzini, had been trained to be a school teacher, but she found it more financially rewarding to work as a seamstress. In Pinocchio, the Blue-Haired Fairy is the one who teaches the puppet to behave and sends him to school, but also lets him learn from his own mistakes.

“I think that this has been overlooked, as she isn’t only the fairy, but also the character of the book who has the power of decision and tells Pinocchio that it’s important to be good,” Kraczyna says. “The little girl that becomes the fairy, who then becomes a grown woman, is still inspired by Giovanna. But, as he goes on in his story, Collodi has glued and superimposed onto this character his ideal of a female figure—leaving one to wonder whether it might be based on his mother.”

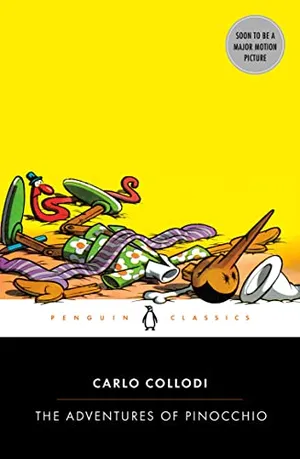

The Adventures of Pinocchio

A revelatory new annotated edition of the most translated Italian book in the world.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(512x463:513x464)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6f/59/6f598b6e-faf3-4b09-adc5-6fa610c74737/gettyimages-872412856.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anto.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anto.png)