The strange late-night phone calls sounded dodgy from the get-go, and James Bond knew it.

Sultry female voices would ask, “Is James there?” Then came a giggle and a click—not the typical call for the noted Philadelphia bird expert.

The year was 1961, and neither Bond nor his wife Mary could figure out what was happening until a friend clued them in: Ian Fleming, the British spy novelist, had confessed to Rogue magazine that he’d stolen his 007’s name from the author of a birding book.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/e2/48e2b7d1-7d05-457b-ac58-a77ab65a3f7b/2_bond_botwi_cover_1936_75_in.jpeg)

“There really is a James Bond, you know, but he’s an American ornithologist, not a secret agent,” Fleming explained in the interview. “I’d read a book of his, and when I was casting about for a natural-sounding name for my hero, I recalled the book and lifted the author’s name outright.”

The book was Birds of the West Indies, published in 1936 after Bond had spent a decade exploring the islands of the Caribbean. The 460-page field guide, which features 159 black-and-white illustrations, became the go-to resource for Fleming, who lived in Jamaica, and many others.

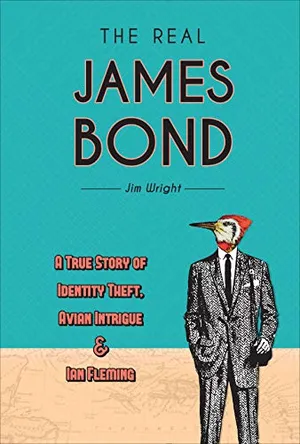

With the long-delayed 25th 007 movie finally upon us (releasing October 8 in the United States), what better time to examine the real Bond? When I researched a newspaper column about the birdman several years ago, I became fascinated with his story—to the point where I realized he deserved to be more than an asterisk in the James Bond multimedia empire. My interest, as a writer and longtime birder, filled the pages of a biography, The Real James Bond, published last year.

Fleming purloined the ornithologist’s name back in 1952 when he wrote his first 007 thriller at Goldeneye, his winter home in Jamaica. Yet it took almost a decade for James Bond to become a household name in the United States. That’s when Life magazine reported that From Russia with Love was one of President John F. Kennedy’s favorite books. And that’s when Bond and his wife Mary started getting those annoying late-night calls.

The Real James Bond: A True Story of Identity Theft, Avian Intrigue, and Ian Fleming

When James Bond published his landmark book, Birds of the West Indies, he had no idea it would set in motion events that would link him to the most iconic spy in the Western world and turn his life upside down.

Although Bond (who went by “Jim”) cared little for the 007 novels, Mary seemed to embrace the connection. She wrote to Fleming and coyly accused him of stealing her husband’s name: “It came to [Jim] as a surprise when we discovered in an interview in Rogue magazine that you had brazenly taken the name of a real human being for your rascal!”

Fleming came clean in a letter to Mary Bond and made three generous offers. He gave Bond “unlimited use of the name Ian Fleming for any purpose he may think fit.” He suggested that Bond discover “a horrible new species” and “christen [it in] insulting fashion” as ”a way of getting back!” And he invited the Bonds to visit Goldeneye so that they could see “the shrine where the second James Bond was born.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/14/f41412a2-122c-46eb-8201-27907c516fde/1_bond_meets_fleming_free_library.jpg)

On February 5, 1964, Jim and Mary Bond stopped by Goldeneye out of the blue. Once Fleming was assured that Bond wasn’t there to sue him, the two authors got along famously—even though Bond immediately got something off his chest.

As Bond told an interviewer later that year: “I confessed to Fleming right off when I met him: ‘I don’t read your books. My wife reads them all but I never do.’ I didn’t want to fly under false colors. Fleming said quite seriously, ‘I don’t blame you.’ ”

When the Bonds went to leave several hours later, Fleming gave them a newly minted first edition of You Only Live Twice and inscribed it boldly on the fly page: “To the real James Bond from the thief of his identity, Ian Fleming, Feb. 5, 1964 (a great day!).”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d6/20/d6204d00-cc69-4aa2-9883-2554e7f372e5/you_only_live_twice_fleming_inscription.jpg)

While researching an upcoming Zoom talk for the Free Library of Philadelphia, which holds the James and Mary Bond archives, I came across a carbon copy of a 1975 typewritten note Mary Bond had written to the head of the library’s Rare Book Department. “The truth of the matter, which I have never publicized, is that I was really angry with Fleming for admitting it was the American J.B. whose name he had snitched,” she wrote. “As the legend grew with continuing episodes and the movies made the name James Bond almost a dirty word, I decided I wanted the personal satisfaction of bringing Fleming and J.B. together so the former could see just what a man he’d done this to. I knew Jim would do nothing about it himself but keep wincing and detesting Ian Fleming. I got that satisfaction the day we lunched with Fleming in Jamaica, too.”

Fleming died six months later, followed soon after by the release of the movie Goldfinger, the third in the collection. Often ranked as the greatest 007 movie of them all, the Sean Connery film featured a gadget-filled Aston Martin DB-5, a henchman named Odd Job, the first “shaken, not stirred" movie martini and Shirley Bassey’s brassy title song. The 007 craze soared to new heights.

In the mid-1960s, no pop-culture phenomenon was as all-consuming as James Bond. Imitators ranged from Dean Martin as big-screen secret agent Matt Helm to Stephanie Powers as “The Girl from U.N.C.L.E.” on American TV. Merchandisers used the 007 imprimatur to peddle nearly anything—bubblegum cards, vodka, aftershave and even “gold” lingerie.

In the meantime, the real Bond increasingly became the target of endless 007 quips, from hotel clerks giving him sly looks to customs officials asking where he was hiding his pistol. Mary Bond, the author of several books of poetry and fiction, fanned the flames by capitalizing on the Fleming connection. Her first effort was How 007 Got His Name, by Mrs. James Bond.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/54/bb54881e-d7f0-4321-8306-66d2e4ac7dd3/4_007_vodka_bottle.jpeg)

As she later conceded in To James Bond With Love, “The trouble was Fleming had stepped out of the picture and had left Jim holding the bag, and Jim wasn’t half as interested in getting some of his own [stature] back as in being left completely out of the limelight.”

When Bond died on Valentine’s Day in 1989, he made the news again—in part because of the connection he could never live down. The New York Times headline noted: “James Bond, Ornithologist, 89; Fleming Adopted Name for 007.”

In 2002, the film Die Another Day cemented the link between the real-life birdman and the fictional secret agent. Pierce Brosnan’s 007 toted the latest edition of Birds of the West Indies to a Havana hotel and told Jinx (played Halle Berry) he was an “ornithologist—only here for the birds.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8e/1f/8e1f7df7-8eba-4a94-b44b-64dee0c103e9/5_mary_bond_reading_how_007.jpg)

Nowadays, the genuine Bond is too often an afterthought, fodder for crosswords and online games. Take this Trivia Genius question from earlier this year: “Who was James Bond named after?”

Sadly, only 22 percent got the correct answer, “C: an ornithologist.”

Bond deserves better. Born into a wealthy Philadelphia family in 1900, Bond moved to England as a 14-year-old after his mother died and his father remarried. He was educated at Harrow and Cambridge’s Trinity College before returning to the United States. After a brief stint as a banker, Bond became an ornithologist at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. From the 1920s through the 1960s, the birdman took more than 100 scientific expeditions to the West Indies. In the days before jet airlines, the seasick-prone Bond traveled by mail ship to the Caribbean for months at a time, island-hopping on tramp steamers, rum runners and banana boats. He explored by foot or on horseback and often lived off the land. The tools of his trade: arsenic (an insecticide for the birds he collected), a knife and a double-barreled shotgun.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/c4/91c48497-a406-46eb-acb7-9e754b89c451/7__wright_streamertail_img_1031.jpg)

Through Birds of the West Indies, Bond helped popularize such exotic fliers as Cuba’s bee hummingbird (the world’s smallest bird) and the breathtaking red-billed streamertail (the national bird of Jamaica). The field guide’s various editions remained in print for seven decades. The Smithsonian Libraries has a first edition of its own.

Bond’s research also resulted in his 1934 landmark zoogeographical theory that the birds of the Caribbean were most closely related to North American birds, not South American, as had previously been thought. This conclusion eventually led the noted evolutionary biologist David Lack to propose that “the Bond Line” be used to denote this boundary.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/de/12de43aa-765d-48d8-b1cd-7ebf84573def/bonds_line_flp.jpeg)

A pioneering conservationist, Bond campaigned for increased protections for birds of all feathers. In his introduction to Birds of the West Indies, Bond wrote: “In no other part of the world … are so many birds in danger of extinction.… It is to be hoped that the island authorities will show more concern for the welfare of their birds so there may yet be a possibility to save the rare species from being annihilated. Bird sanctuaries should be created where no hunting of any kind is permitted.”

Over four decades, Bond collected more than 290 of the 300 bird species known to the West Indies. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and other top museums are home to the birds, fish, frogs and insects that Bond collected.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/30/d7/30d70b23-bbdf-4f80-a8e4-8c4b3e0b0cb2/8_hayes_bahama_nuthatch_long_shot_img_7607.jpeg)

Bond’s research continues to pay dividends. This summer, the American Ornithological Society announced that the Bahama nuthatch, a bird Bond discovered on Grand Bahama in 1931, is a distinct species. Alas, after several major hurricanes in recent years, it has likely gone extinct in the meantime.

Ornithologist Jason Weckstein of the Academy of Natural Sciences (now affiliated with Drexel University), says the two nuthatches that Bond collected nine decades ago remain invaluable: “They are the only thing we have to go back to with regard to extinct and in many cases highly endangered species such as this. This may be the only way we learn from our mistakes.”

The real Bond would be proud, but mostly sad.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(770x623:771x624)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d5/2d/d52d8f4f-118d-4fa5-bda0-52262ad01767/6-7james_bond_with_eskimo_curlew.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jim_Wright_headshot_Watson1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jim_Wright_headshot_Watson1.jpg)