Why are Honeybees and Skyscrapers Sweet for Each Other?

It’s not just about the honey. The humble honeybee is starting to play a greater role in the design of urban living

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130904102037hive-city_470.jpg)

It’s been five years now since it was reported that, for the first time ever, more than half of the world’s population live in urban areas. Such a dramatic demographic shift comes with inevitable consequences – some predictable, like rising housing prices and greater economic disparity, and some less so, like the rise in urban honeybee population. With growing interest in sustainability and local food production combined with news stories and documentaries about honeybee colony collapse disorder, recent changes in laws, and the growing urban population, urban beekeeping is a full-blown trend. But it’s not just about the honey. The humble honeybee is starting to play a greater role in the design of urban living.

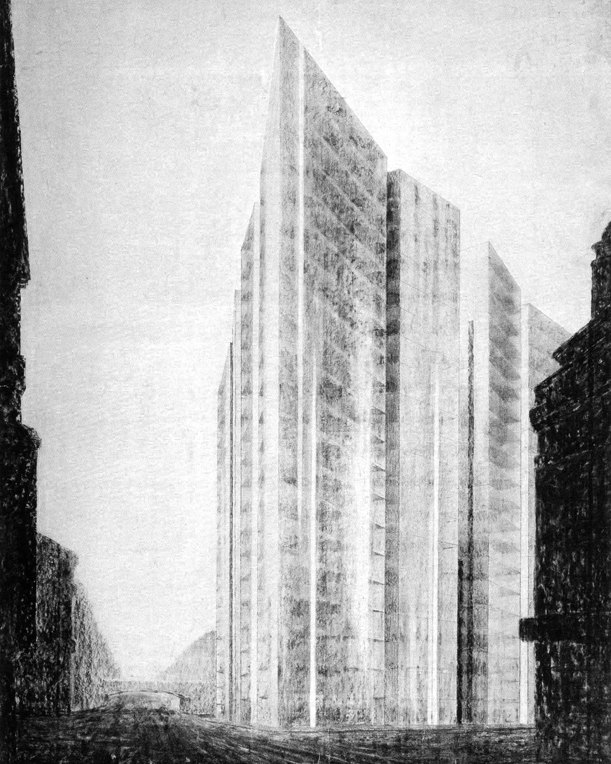

The Bank of American Tower by Cook Fox architects. Somewhere in that image 100,000 bees are buzzing 51 stories above New York City (image: Cook Fox)

Bees can help maintain the green roofs that are becoming more common in big cities and thus, in some small way, contribute to a building’s LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating, which is a metric of sustainability promoted by the United States Green Building Council based on a system of points awarded for environmentally friendly features. In Manhattan, for example, the rooftop hives atop The Bank of America Tower, a 51-story glass skyscraper in the heart of Midtown, were recently featured in The New York Times. The towers’s 6,000-sq-ft green roof is a critical element of its LEED Platinum rating –the highest possible– and is sustained in part by two hives of 100,00 honey bees.

Buildings can benefit from bees in other ways. While some urban bees help secure sustainability credentials as green roof gardeners, others are security guards. In response to a 2010 article in The Telegraph about the recurring theft of lead from the roofs of historic buildings, architect Hugh Petter described the unique counter-measure taken by one building owner in York:

“The flat roofs of this historic building are now the home of bees — this keeps the hives away from the public in urban areas, provides delicious honey for the local community and acts as a powerful disincentive for anyone minded to remove the lead.”

Petter reports that once the bees were installed, the thefts stopped. Unfortunately, according to another recent story, such apian theft deterrents might themselves become the target of thieves. Due to colony collapse disorder, honey bees are so rare that bee theft is on the rise. A problem once common to cattle ranchers on the range is now a problem for beekeepers in Brooklyn. And until someone invents a branding iron small enough for a bee, there’s no way to prove that your queen bee was stolen.

“Elevator B,” an architectural beehive designed by students at the University of Buffalo (image: Hive City)

More recently, a group of architecture students at the University of Buffalo decided that, rather than adding bees to their buildings, they would actually design buildings for bees. “Elevator B” is a 22-ft-tall steel tower clad in hexagonal panels inspired by the natural honeycomb structure of beehives and designed to optimize environmental conditions. Bees don’t occupy the full height of the structure, just a cypress, glass-bottomed box suspended near the top. Human visitors can enter the tower through an opening at its base and look up to see the industrious insects at work while beekeepers can tend to the bees and collect their honey by lowering the box like an elevator. If the stacked boxes of the modern beehive are efficient public housing projects, this is a high-rise luxury tower. Although it should be mentioned that the bees were forcibly relocated from their colony in the boarded-up window of an abandoned building and may very well have been happier there. But such is progress. Apparently even bees aren’t exempt from eminent domain laws. Perhaps this skyscraper for bees will mark a new trend in honeybee gentrification.

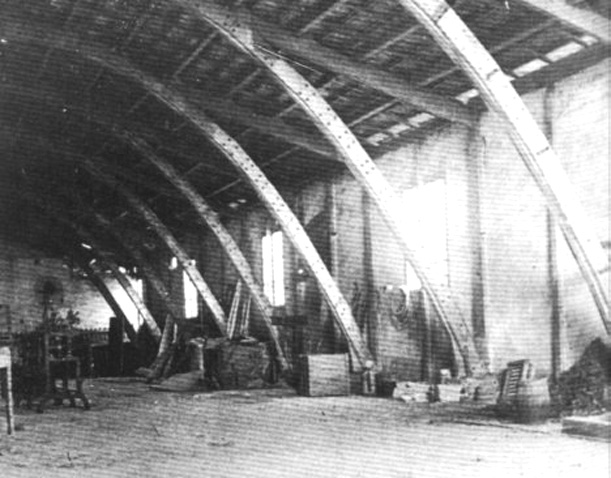

Architects have long been fascinated with bees. According to architectural historian Juan Antonio Ramirez architects as different as Antoni Gaudi (1852-1926) and Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) drew inspiration from bees and beehives. Ramirez believes that Gaudi’s use of catenary arches in his organic, idiosyncratic designs –first represented in his Cooperativa Mataronesa factory– were directly inspired by the form of natural beehives. He supports this claim is with the Gaudi-designed graphics that accompany the project: a flag with a bee on it and a coat-of-arms representing workers as bees – a symbol for industriousness and cooperation. Gaudi was building a hive for humans.

Mies van der Rohe’s 1921 Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper Project. Codename: Honeycomb (image: wikiarquitectura)

Noted minimalist architect Mies van der Rohe (whose work has been immortalized in Lego) was less inspired by the form in which bees built than by the ideal industrial society they represented. In the aftermath of World War I, a young, perhaps slightly more radical Mies was associated with a group of writers, artists, and architects known as the Expressionists. He published designs for innovative glass high-rises –the first of their kind– in the pages of the Expressionist publication Frülicht. Such buildings, Mies wrote, “could surely be more than mere examples of our technical ability….Instead of trying to solve the new problems with old forms, we should develop the new forms from the very nature of the new problems.” One of the most famous of these early unbuilt designs is the 1921 project nicknamed “honeycomb”. In Ramirez’s view, the angular glass skyscraper is evidence that Mies wasn’t only looking into the nature of the new problems, but looking into nature itself – specifically, to bees. Mies’s youthful belief that architecture could reshape society “brings him closer to the idea of the beehive, because in the beehive we find a perfect society in a different architecture.”

This is seriously the best free picture I could find of Rosslyn Chapel. You should google it. It’s really beautiful and the stone beehives are cool. (image: wikimedia commons)

Architecture’s relationship with bees predates green roof hives, Mies, and even Gaudi. As evidenced by a recent discovery at Rosslyn Chapel, perhaps best known as the climactic location of The Da Vinci Code, precedent for bee-influenced architecture can be traced back to the 15th century. While renovation the chapel a few years ago, builders discovered two stone beehives carved into the building as a form of architectural ornament. There’s just a small entry for bees through an ornamental stone flower and, surprisingly, no means to collect honey. Appropriately, the church is simply a sanctuary for bees. Una Robertson, historian of the Scottish Beekeepers Association told The Times that “Bees do go into roof spaces and set up home, and can stay there a long time, but it’s unusual to want to attract bees into a building…Bees have been kept in all sorts of containers , but I have never heard of stone.” Maybe the 600-year-old stone hive should be a model for urban farmers and green architects everywhere. Instead of adding a beehive to your building, why not design one into it?

Unfortunately, much like the urbanization of the world’s population, urban beekeeping might not be sustainable. Overpopulation and limited resources is a problem for every species. In Europe at least, cities such as London, where there are are 25 beehives per square mile, just don’t have enough flowers to support the rising urban bee population. Perhaps urban bees will ultimately suffer the same inevitable fate as humans: replacement by robot.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)