Why Ellsworth Kelly Was a Giant in the World of American Art

The artist’s minimalism put the essence of his subjects above all

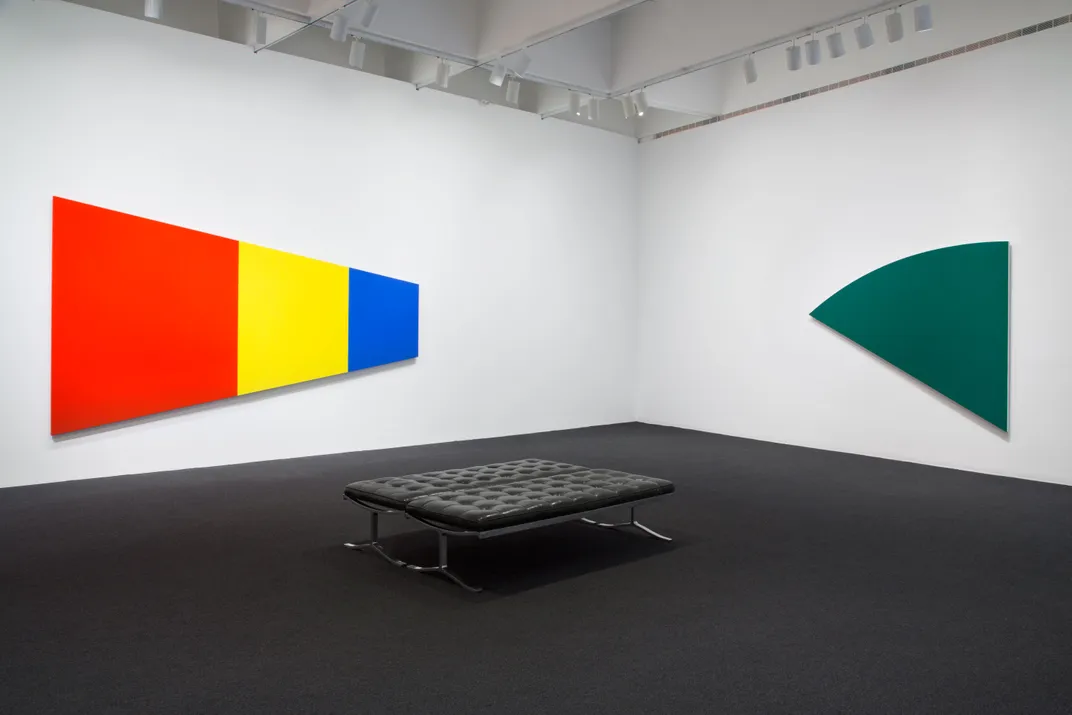

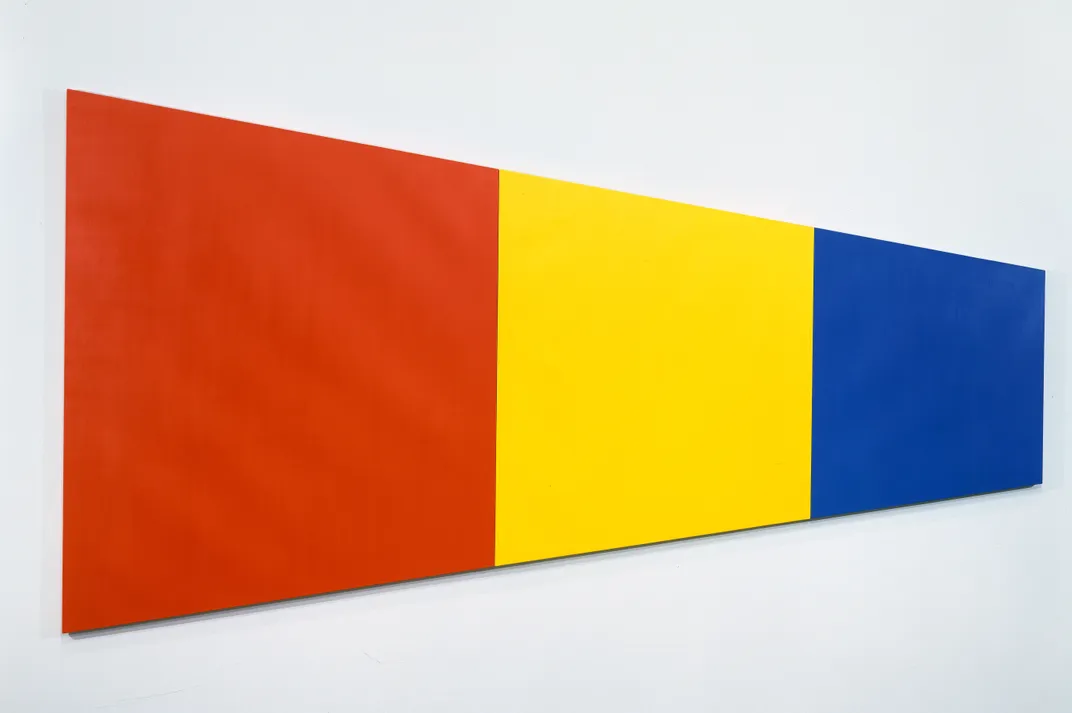

Ellsworth Kelly, considered one of the great American artists of the 20th century for his pioneering work in minimalist painting and sculpture, died Sunday in his Spencertown, New York, home, at the age of 92. Recognized for his vivid use of geometric blocks and intense colors, Kelly built over seven decades a reputation for colorful abstraction and works that explored the essence of their subjects.

His earliest works of art were created in service to the United States, as part of a special camouflage unit in France during World War II. Kelly and his fellow artist-soldiers were tasked with fooling the Germans—using rubber and wood to construct fake tanks and trucks—into thinking the multitudes of Allied troops on the battlefield were much larger than reality. While this seems an unconventional early training for an artist, it proved a fitting one for Kelly.

“He was able to understand that there were these realities that for most of us are camouflaged,” says Virginia Mecklenburg, chief curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “He would evoke those realities—a distinct feel of gravity, or the physics of weight and momentum that we rarely think about in tangible terms. He was able to get that across.”

After his service, Kelly enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and returned to Paris in 1948, absorbing an array of influences, including Picasso and Matisse, Asian art and Romanesque churches. He came back to the United States and presented his first solo show in 1956. Three years after that, Kelly’s work was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) 16 Americans exhibition. His geometric abstract works, along with those of other American painters including Ad Reinhardt and Brice Marden, was dubbed “hard-edge painting” by art historian Jules Langsner in 1959.

Throughout the 1960s, he carved out his own niche separate from the New York City and Paris art worlds. Mecklenburg says what she finds remarkable about his work was the way he pared down the architecture, images, and other visuals he saw in the world and in art, turning them into direct, visceral abstractions. Using basic colors—blue, green, white, black—and single canvases (later moving into multiple canvases and sculpture) he created statements that were “less descriptive than evocative,” as she puts it.

“They take time to look at, but once you step back, you realize you are looking at something you have seen over and over again,” says Mecklenburg, giving the example of the 1961 painting “Blue on White” on exhibit in the American Art Museum, which she says evokes a leaf unfurling. “All of a sudden you begin to understand that if you dissociate narrative ideas, how strong the visual impulse is in every human being.”

He showed at the Venice Biennale in 1966 (and would show at three more in subsequent years), had his first American retrospective at MoMA in 1973, and his first major European retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam six years after that.

“Ellsworth Kelly made the transition from postwar geometric abstraction to the Minimalist movement that began in the early 1970s,” says Valerie Fletcher, senior curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, which possesses 22 of Kelly’s works, including “White Relief over Dark Blue” from 2002, on view in the museum’s third floor, and an untitled 1986 sculpture displayed in the garden. “If you look at his paintings compared to others in his generation, they are far simpler.”

Some of these works take on a “totemic” quality, as Mecklenburg describes it, pointing to “Memorial,” his wall sculpture of four white panels at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “How do you talk about something of that magnitude?” she asks. “There are either a million words or no words, and he chose no words.”

His simple, geometric approach had an impact on the next generation of Minimalists—Frank Stella, Donald Judd, and others—with works that explored the essence of ideas or emotions in tangible and tactile ways.

“He had a huge impact on the art world, but the work speaks in a visceral way to whoever looks at it,” adds Mecklenburg. “I have to say there is a sense of joy and a sense of energy to so much of his work. You sort of come back to the center when you look at it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)