Why Is the Genie in ‘Aladdin’ Blue?

There’s a simple answer and a colonialist legacy for why the genie looks the way it does

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/37/9b377dc7-f7ac-4fd3-92dc-79cf178cbb0b/genie-aladdin.jpeg)

Like the late Robin Williams-animated incarnation before him, Will Smith promised that his genie in the Guy Ritchie live-action remake of Disney’s Aladdin would be blue. And, as revealed to the world in the movie’s latest trailer, Smith’s version of the fast-talking genie with a heart of gold is undeniably blue. He’s blue like Violet Beauregarde after she chewed the experimental gum in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory blue. He’s blue like Tobias Funke when he attempted to join Blue Man Group in “Arrested Development” blue. Smith’s genie is so blue that it makes you start to wonder how the wish-granting genie of the lamp came to look that way in the first place.

Eric Goldberg, who was the supervising animator for the genie in the original 1992 animated Aladdin, had a simple answer for why the Disney genie looks the way he does. “I can tell you exactly,” he says, citing the film’s distinctive color script, as developed by then-Disney production designer Richard Vander Wende. “The reds and the darks are the bad peoples’ colors,” Goldberg says. “The blues and the turquoises and the aquas are the good peoples’ colors.” So, if Williams’ warm baritone didn’t instantly clue you in on the genie’s moral fiber, the clear-as-day blue coloring was there to telegraph him as one of the good guys (in turn, Aladdin’s foil, the evil Jafar, turns scarlet when he gets genie-fied).

Vander Wende adds more to the story over email. The color blue itself was an intentional choice, he says, grounded in the resilience of Aladdin and his allies. “Certain blues in Persian miniatures and tiled mosques stand out brilliantly in the context of the sun-bleached desert,” he writes, “their suggestion of water and sky connoting life, freedom, and hope in such a harsh environment.”

The overall visual development of Aladdin, including every individual character and location, was “a long, evolutionary process,” he writes. After he started at Disney in 1989, the head of the department at that time had tapped him to start working on Aladdin while the studio’s The Little Mermaid finished wrapping. With no working script yet in hand, Vander Wende began researching original folk tales and references in art and historical materials to help inform his spec art.

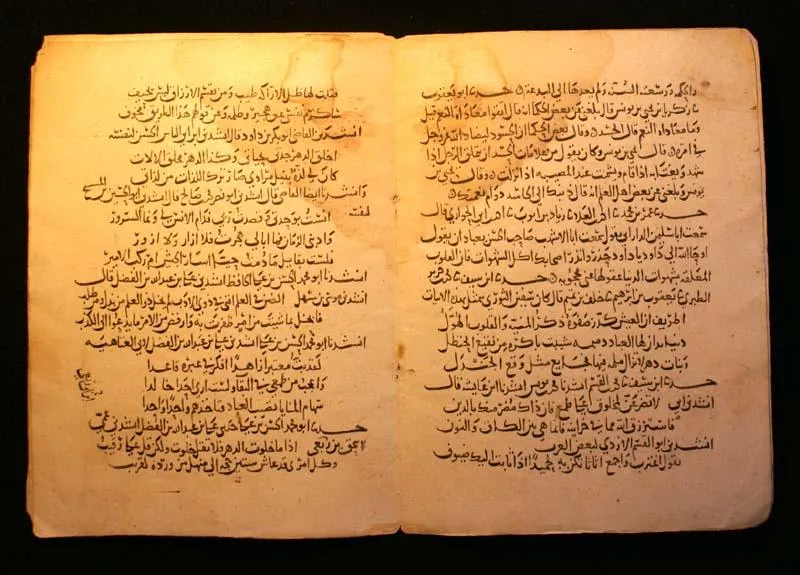

The story of Aladdin is one of the most well-known works in One Thousand and One Nights (Alf Layla wa Layla) or Arabian Nights, the famous collection of folk stories compiled over hundreds of years, largely pulled from Middle Eastern and Indian literary traditions. Genies, or Jinn, make appearances throughout the stories in different forms. A rich tradition in Middle Eastern and Islamic lore, Jinn appear in the Qur’an, where they are described as the Jánn, “created of a smokeless fire,” but they can even be found in stories that date back before the time of Muhammad in the 7th century.

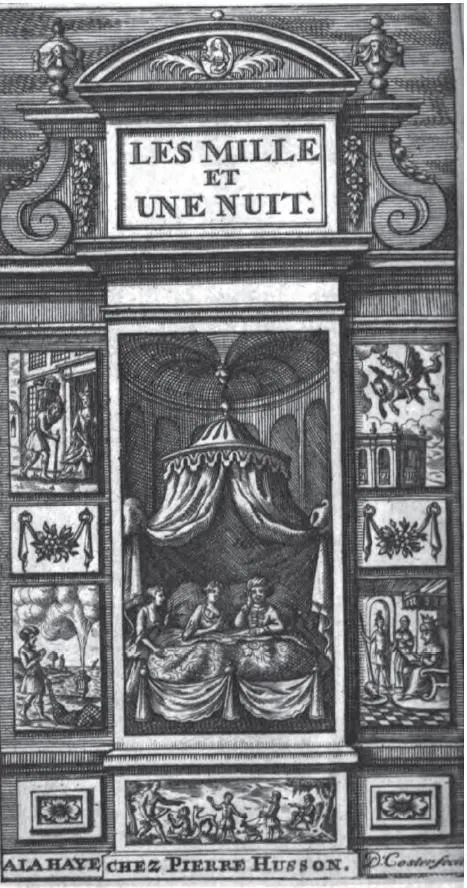

The pop culture genie of Nights we recognize today, however, was shaped by European illustrators, beginning with the frontpieces done for 18th-century translator Antoine Galland’s Les Mille et Une Nuits.

Galland was the first to translate the tales for a European audience. (Incidentally, he is also credited with adding the story of Aladdin, which was initially set in China with a Chinese Muslim cast of characters, to the anthology after learning the story from Ḥannā Diyāb, a Maronite Syrian from Aleppo, as historian Sylvette Larzul has documented, and whose legacy Arafat A. Razzaque, a Ph.D candidate in history & Middle Eastern studies at Harvard recently detailed.)

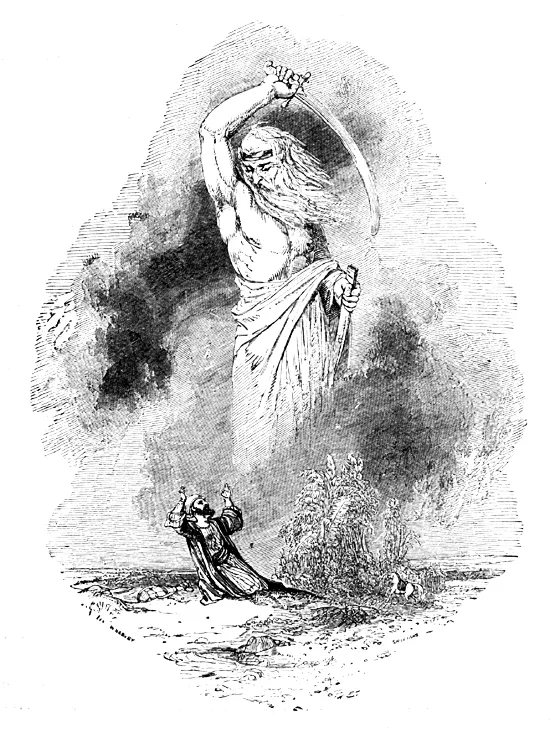

Dutch artist David Coster did the frontpieces for Galland’s Nights, so it’s under his hand, as Nights scholar Robert Irwin chronicles for the Guardian, that we get our first Westernized illustration of the genie. It’s a far cry from the Disney version: the genie, Irwin writes, appears like “a very large man in a tattered robe.”

At the time, French writers often used what was then referred to as the Orient—a term indiscriminately used to refer to North Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East more generally—to allude to its own society and monarchy, explains Anne E. Duggan, professor of French at Wayne State University, who’s studied the visual evolution of the genie. “You can see that the genie is assimilated into what would be familiar,” she says, pointing out that illustrations during that time that depicted the genie alternatively as a giant, an archangel, Greek or Roman Gods, and even a vampire.

The character illustrations of the genie were in line with the way Europeans viewed the Arab world at that time—“as being different but not fundamentally different,” as Duggan puts it.

Once European colonialism expanded, however, she began to observe “essentialized differences” manifest in Nights translation. “In the 19th century everything associated with Nights gets an imperialistic twist to it, so it becomes more racist,” she says.

That started with the text, which saw the genie morph away from “free-willed, potentially dangerous jinn of Arab folklore,” as anthropologist Mark Allen Peterson argues in From Jinn to Genies: Intertextuality, Media, and the Making of Global Folklore, into the “enslaved gift-giving genies of global folklore” that we recognize today.

The visual language of the genie followed. Duggan, who traced those increasingly racialized depictions in an article published in the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts in 2015, says that change can be seen in Edward Lane’s popular three-volume translation of Nights published in 1839-41, in which a sexually charged genie in “The Lady of the Rings” is depicted as black while a genie, not associated with sex, in “The Merchant and the Jinee” is depicted as white.

By the turn of the 20th century, the enslaved genie appeared like caricatures of people living throughout the Middle East and North Africa region. A hooked nose, for instance, is given to the dark-skinned genie in Edmund Dulac's 1907 illustration for "The Fisherman and the Genie.” One particularly damning set of 1912 illustrations for Nights that Duggan draws attention to are done by Irish illustrator René Bull, whose color illustrations depict dark-skinned genies with "big, bulging eyes ...thick lips, and white teeth.”

As the genie jumped from the page to the screen in the 20th century, the colonial legacy lingered. “We don't realize there’s a history behind the genie being represented the way he is. And that is part of a colonial legacy, even if people don’t intend it that way, that's how it gets shaped over time,” says Duggan.

But just as the racialized look of the genie was thrust upon the character, the genie isn't tied to that depiction. Since the late 1990s, Duggan has observed a growing interest in the return to a more authentic representation of the Jinn.

For the 1992 Disney film, Vander Wende’s first sketches of the genie were actually inspired by the original descriptions of the Jinn in folklore, those “capricious forces of nature,” as he puts it, “who could be menacing or benevolent depending on the whim of circumstance.”

But the movie’s co-directors instead hoped to have Robin Williams’ high-energy personality inform much of his character. Williams’ gift for impressions molded Aladdin’s genie with his own imprimatur, taking on the visage of real-life people as varied as conservative intellectual William F. Buckley and television talk-show host Arsenio Hall. Visually inspired by the caricatures of celebrity cartoonist Al Hirschfeld, the genie’s appearance also matched what Vander Wende referred to as the “tautly sinuous contours” he sought for Aladdin.

We’ll have to wait for the release to see how Smith reinvents the genie once again. But the time is ripe, says Duggan, for a “more mindful and post-colonial vision” of the genie to come out of the lamp. A genie that—to go back to the original question—has no historical need, at least, to be blue.