Why is Rem Koolhaas the World’s Most Controversial Architect?

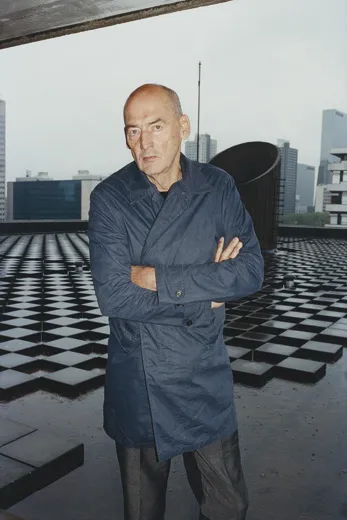

Age has not tempered the Dutch architect, who at 67 continues to shake up the cultural landscape with his provocative designs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rem-Koolhaus-portrait-631.jpg)

Rem Koolhaas has been causing trouble in the world of architecture since his student days in London in the early 1970s. Architects want to build, and as they age most are willing to tone down their work if it will land them a juicy commission. But Koolhaas, 67, has remained a first-rate provocateur who, even in our conservative times, just can’t seem to behave. His China Central Television headquarters building, completed this past May, was described by some critics as a cynical work of propaganda and by others (including this one) as a masterpiece. Earlier projects have alternately awed and infuriated those who have followed his career, including a proposal to transform part of the Museum of Modern Art into a kind of ministry of self-promotion called MoMA Inc. (rejected) and an addition to the Whitney Museum of American Art that would loom over the existing landmark building like a cat pawing a ball of yarn (dropped).

Koolhaas’ habit of shaking up established conventions has made him one of the most influential architects of his generation. A disproportionate number of the profession’s rising stars, including Winy Maas of the Dutch firm MVRDV and Bjarke Ingels of the Copenhagen-based BIG, did stints in his office. Architects dig through his books looking for ideas; students all over the world emulate him. The attraction lies, in part, in his ability to keep us off balance. Unlike other architects of his stature, such as Frank Gehry or Zaha Hadid, who have continued to refine their singular aesthetic visions over long careers, Koolhaas works like a conceptual artist—able to draw on a seemingly endless reservoir of ideas.

Yet Koolhaas’ most provocative—and in many ways least understood—contribution to the cultural landscape is as an urban thinker. Not since Le Corbusier mapped his vision of the Modernist city in the 1920s and ’30s has an architect covered so much territory. Koolhaas has traveled hundreds of thousands of miles in search of commissions. Along the way, he has written half a dozen books on the evolution of the contemporary metropolis and designed master plans for, among other places, suburban Paris, the Libyan desert and Hong Kong.

His restless nature has led him to unexpected subjects. In an exhibition first shown at the 2010 Venice Biennale, he sought to demonstrate how preservation has contributed to a kind of collective amnesia by transforming historic districts into stage sets for tourists while airbrushing out buildings that represent more uncomfortable chapters in our past. He is now writing a book on the countryside, a subject that has been largely ignored by generations of planners who regarded the city as the crucible of modern life. If Koolhaas’ urban work has a unifying theme, it is his vision of the metropolis as a world of extremes—open to every kind of human experience. “Change tends to fill people with this incredible fear,” Koolhaas said as we sat in his Rotterdam office flipping through an early mock-up of his latest book. “We are surrounded by crisismongers who see the city in terms of decline. I kind of automatically embrace the change. Then I try to find ways in which change can be mobilized to strengthen the original identity. It’s a weird combination of having faith and having no faith.”

Tall and fit in a tapered dark blue shirt, with inquisitive eyes, Koolhaas often seems impatient when talking about his work, and he frequently gets up to search for a book or an image. His firm, OMA, for the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, employs 325 architects, with branches in Hong Kong and New York, but Koolhaas likes the comparative isolation of Rotterdam, a tough port city. Housed in a brawny concrete and glass building, his office is arranged in big, open floors, like a factory. On the Sunday morning we met, a dozen or so architects sat silently at long worktables in front of their computers. Models of various projects, some so big you could step inside them, were scattered everywhere.

Unlike most architects of his stature, Koolhaas participates in many competitions. The process allows for creative freedom, since a client isn’t hovering, but it’s also risky. The firm invests an enormous amount of time and money in projects that will never get built. To Koolhaas, this seems to be an acceptable trade-off. “I’ve absolutely never thought about money or economic issues,” Koolhaas said. “But as an architect I think this is a strength. It allows me to be irresponsible and to invest in my work.”

Koolhaas’ first test of his urban theories came in the mid-1990s, when he won a commission to design a sprawling development on the outskirts of Lille, a rundown industrial city in northern France whose economy was once based on mining and textiles. Linked to a new high-speed rail line, the development, called Euralille, included a shopping mall, conference and exhibition center, and office towers surrounded by a tangle of freeways and train tracks. Seeking to give it the richness and complexity of an older city, Koolhaas envisioned a pileup of urban attractions. A concrete chasm, crisscrossed by bridges and escalators, would connect an underground parking garage to a new train station; a row of mismatched office towers would straddle the station’s tracks. For added variety, celebrated architects were brought in to design the various buildings; Koolhaas designed the convention hall.

More than a decade after its completion, Koolhaas and I meet in front of Congrexpo, the convention hall, to see how the development looks today. An elliptical shell, the colossal building is sliced into three parts, with a 6,000-seat concert hall at one end, a conference hall with three auditoriums in the middle and a 215,000-square-foot exhibition space at the other.

On this Saturday afternoon the building is empty. Koolhaas had to notify city officials to get access, and they’re waiting for us inside. When Koolhaas was hired to design the building, he was still perceived as a rising talent; today he is a major cultural figure—a Pritzker Prize-winning architect who is regularly profiled in magazines and on television—and the officials are clearly excited to meet him. His presence seems to bring cultural validity to their provincial city.

Koolhaas is polite but seems eager to escape. After a cup of coffee, we excuse ourselves and begin to navigate our way through the hall’s cavernous rooms. Occasionally, he stops to draw my attention to an architectural feature: the moody ambience, for instance, of an auditorium clad in plywood and synthetic leather. When we reach the main concert space, a raw concrete shell, we stand there for a long while. Koolhaas sometimes seems to be a reluctant architect—someone who is unconcerned with conventional ideas of beauty—but he is a master of the craft, and I can’t help marveling at the intimacy of the space. The room is perfectly proportioned, so that even sitting at the back of the upper balcony you feel as though you were pressing up against the stage.

Yet what strikes me most is how Koolhaas was able to express, in a single building, bigger urban ideas. Congrexpo’s elliptical, egg-like exterior suggests a perfectly self-contained system, yet inside is a cacophony of competing zones. The main entry hall, held up by imposing concrete columns, resembles a Roman ruin encased in a hall of mirrors; the exhibition space, by contrast, is light and airy. The tension created between them seems to capture one of Koolhaas’ principal preoccupations: How do you allow the maximum degree of individual freedom without contributing to the erosion of civic culture?

The rest of Euralille is a bit of a letdown. The development lacks the aesthetic unity that we associate with the great urban achievements of earlier eras and that, for better or worse, give them a monumental grandeur. Because of a tight budget, many of the building materials are cheap, and some haven’t worn well. The high-speed train station, designed by Jean-Marie Duthilleul, feels coarse and airless despite vast expanses of glass. The addition of metal cages above the station’s bridges and escalators, to prevent people from throwing refuse onto the tracks, only makes the atmosphere more oppressive.

With time, however, I discern a more subtle interplay of spaces. The triangular plaza acts as a calming focal point at the development’s heart, its surface sloping down gently to a long window where you can watch trains pulling slowly in and out of the station. By contrast, the crisscrossing bridges and escalators, which descend several stories to a metro platform behind the station, conjure the vertiginous subterranean vaults of Piranesi’s 18th-century etchings of imaginary prisons. Up above, the towers that straddle the station, including a striking boot-shaped structure of translucent glass designed by Christian de Portzamparc, create a pleasant staccato effect in the skyline.

Best of all, Euralille is neither an infantile theme park nor a forbidding grid of synthetic glass boxes. It is a genuinely unpretentious, populist space: Streets filled with high-strung businessmen, sullen teenagers and working-class couples pulse with energy. This difference is underscored later as we stroll through Lille’s historic center a few blocks away, where the refurbished pedestrian streets and dolled-up plaza look like a French version of Disney’s Main Street.

Koolhaas’ achievement at Euralille is not insignificant. In the time since the development’s completion, globalization has produced a plethora of urban centers that are as uniform and sterile as the worst examples of orthodox Modernism—minus the social idealism. What was once called the public realm has become a place of frenzied consumerism monitored by the watchful eyes of thousands of surveillance cameras, often closed off to those who can’t afford the price of membership.

In this new world, architecture looks more and more like a form of corporate branding. Those who rose through the professional ranks once thinking they would produce meaningful public-spirited work—the libraries, art museums and housing projects that were a staple of 20th-century architecture—suddenly found themselves across the table from real estate developers and corporate boards whose interests were not always so noble-minded. What these clients thirsted for, increasingly, was the kind of spectacular building that could draw a crowd—or sell real estate.

Koolhaas was born in Rotterdam in 1944, during the Allied bombardment, and grew up in a family of cultured bohemians. A grandfather was an architect who built headquarter buildings for the Dutch airline KLM and the state social security administration; his father wrote magical realist novels and edited a leftist weekly paper. After the war, the family moved to Amsterdam, where Koolhaas spent afternoons playing in the rubble of the state archive building, which had been blown up by the resistance during the German occupation.

His first experience with a mega-city and all of its moral contradictions was as a boy in Jakarta, Indonesia, where his father ran a cultural institute under the revolutionary Sukarno, who had led the country’s struggle for independence. “I had never seen such poverty,” Koolhaas said. “And I almost instantly understood that it was impossible to pass judgment on what you saw. On some level you could only accept it as reality.”

Back in Amsterdam in his early 20s, Koolhaas avoided radical politics, joining a small group of Dutch Surrealist writers at the fringes of the European cultural scene. “There were two kinds of ’60s,” he said to me. “One was avant-garde, highly modernist— Antonioni, Yves Klein. The other was the Anglo-Saxon, hippie-ish, political side. I associated with the avant-garde tendency.” Koolhaas worked briefly as a journalist, writing a profile mocking a vision by the artist-architect Constant Nieuwenhuys for a post-capitalist paradise suspended hundreds of feet above the city on a huge steel frame. A later story satirized the Provos—a group of young Dutch anarchists whose actions (planning to disrupt a royal wedding with smoke bombs) were intended to goad the Dutch authorities. Koolhaas even co-wrote a screenplay for the raunchy B-movie king Russ Meyer. (The film was never made.)

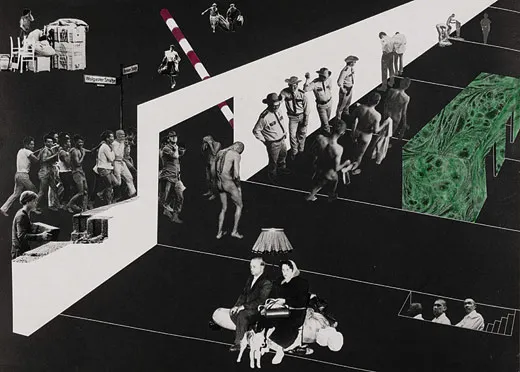

By the time Koolhaas got to London’s Architectural Association, in the late 1960s, he had established himself as an audacious thinker with a wicked sense of humor. The drawings he produced for his final project, which are now owned by MoMA, were a brash sendup of Modernist utopias and their “afterbirths.” Dubbed “The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture,” the project was modeled partly after the Berlin Wall, which Koolhaas described as a “masterpiece” of design that had transformed the western half of the city into an irresistible urban fantasy. Koolhaas’ tongue-in-cheek proposal for London carved a wide swath through the center to create a hedonistic zone that could “fully accommodate individual desires.” As the city’s inhabitants rushed to it, the rest of London would become a ruin. (Galleries and museums ask to borrow the Koolhaas drawings more often than anything else in MoMA’s architecture and design collections.)

Koolhaas’ book Delirious New York cemented his reputation as a provocateur. When Koolhaas wrote it, in the mid-1970s, New York City was in a spiral of violence and decay. Garbage was piling up on streets, slumlords were burning down abandoned tenements in the South Bronx to collect on insurance and the white middle class was fleeing to the suburbs. For most Americans, New York was a modern Sodom.

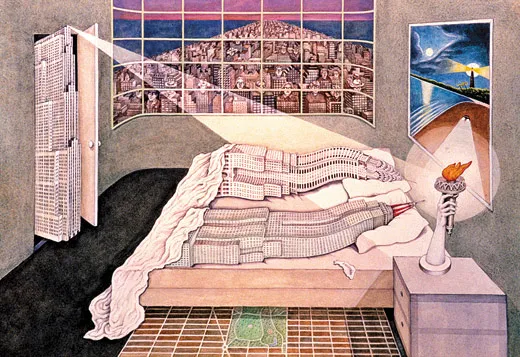

To Koolhaas, it was a potential urban paradise. With his new wife, the Dutch artist Madelon Vriesendorp, he saw a haven for outsiders and misfits. Manhattan’s generic grid, he argued, seemed capable of accommodating an intoxicating mix of human activities, from the most extreme private fantasy to the most marginal subculture. The book’s positive spin was underscored by the cover: an illustration by Vriesendorp of the Empire State and Chrysler buildings lying side by side in a post-coital slumber. “It was geared against this idea of New York as a hopeless case,” Koolhaas told me. “The more implausible it seemed to be defending it, the more exciting it was to write about.”

These early ideas began to coalesce into an urban strategy in a series of projects in and around Paris. In a 1991 competition for the expansion of the business district of La Défense, for instance, Koolhaas proposed demolishing everything but a few historic landmarks, a university campus and a cemetery; the rest would be replaced with a new Manhattan-style grid. The idea was to identify and protect what was most precious, then create the conditions for the urban chaos that he so loved to take hold.

More recently, Koolhaas has responded to what he termed “the excessive compulsion toward the spectacular” by pushing his heretical work to greater extremes. Architecturally, his recent designs can be either deliciously enigmatic or brutally direct. The distorted form of his CCTV building, for example—a kind of squared-off arch whose angled top cantilevers more than 500 feet above the ground—makes its meaning impossible to pin down. (Martin Filler condemned it in the New York Review of Books as an elaborate effort to impart a “bogus semblance of transparency” on what is essentially a propaganda arm of the Chinese government.) Seen from certain perspectives its form looks hulking and aggressive; from others it looks almost fragile, as if the whole thing were about to tip over—a magnificent emblem for uncertain times. By contrast, the Wyly Theatre in Dallas (2009) is a hyper-functional machine—a gigantic fly tower with movable stages and partitions encased inside an 11-story metal box.

At the same time, his urban work has begun to seem increasingly quixotic. In a 2001 development plan for Harvard University, which was expanding across the Charles River into nearby Allston, Koolhaas proposed diverting the path of the river several miles to create a more unified campus. The idea seemed preposterous, and Harvard’s board quickly rejected it, but it carried a hidden message: America’s astonishing growth during the first three-quarters of the 20th century was built largely on the hubris of its engineers. (Think of the Los Angeles depicted in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, a city that diverted water across 250 miles of desert to feed the growth of the San Fernando Valley.) Why, Koolhaas seemed to be asking, aren’t such miracles possible today?

In a 2008 competition for a site off the coast of Dubai, Koolhaas went out on another limb, proposing a development that resembled a fragment of Manhattan that had drifted across the Atlantic and lodged itself in the Persian Gulf—a kind of “authentic” urban zone made up of generic city blocks that would serve as a foil to Dubai’s fake glitz.

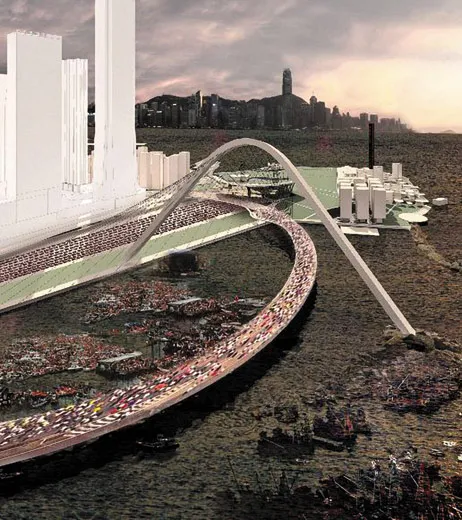

His most convincing answer to the vices of global urbanization was a proposal for the West Kowloon Cultural District, a sprawling 99-acre cultural and residential development to be built on landfill on a site overlooking Hong Kong Harbor. Koolhaas traveled to Hong Kong every month for more than a year to work on the project, often wandering up into the surrounding mountains. Inspired by the migrant dwellings and rural marshlands that he found there, he proposed three “urban villages” arranged along a spacious public park. The idea was to create a social mixing bowl for people of different cultural, ethnic and class backgrounds. “In spite of its metropolitan character Hong Kong is surrounded by countryside,” Koolhaas said. “We felt that we’d discovered a really wonderful prototype. The villages were not only a very beautiful urban model, but they would be sustainable.”

The experience ended in disappointment. After more than a year of work on the proposal, Koolhaas lost to Norman Foster, whose projects are known for high-tech luster.

More troubling perhaps to Koolhaas, the architectural climate has become more conservative, and hence more resistant to experimental work. (Witness the recent success of architects like David Chipperfield, whose minimalist aesthetic has been praised for its comforting simplicity.)

As someone who has worked closely with Koolhaas put it to me: “I don’t think Rem always understands how threatening his projects are. The idea of proposing to construct villages in urban Hong Kong is very scary for the Chinese—it is exactly what they are running away from.”

Yet Koolhaas has always sought to locate the beauty in places that others might regard as so much urban debris, and by doing so he seems to be encouraging us to remain more open to the other. His ideal city, to borrow words he once used to describe the West Kowloon project, seems to be a place that is “all things to all people.”

His faith in that vision doesn’t seem to have cooled any. One of his newest projects, a performing arts center under construction in Taipei, fuses the enigmatic qualities of CCTV with the bluntness of the Wyly Theatre. And he continues to pursue urban planning projects: Sources in the architecture community say he recently won a competition to design a sprawling airport development in Doha, Qatar (the results have not been made public). If it is built, it’ll become his first major urban project since Euralille.

Koolhaas first thought of writing a book about the countryside while walking with his longtime companion, the designer Petra Blaisse, in the Swiss Alps. (Koolhaas separated from his wife some years ago and now lives with Blaisse in Amsterdam.) Passing through a village, he was struck by how artificial it looked. “We came here with a certain regularity and I began to recognize certain patterns,” Koolhaas said. “The people had changed; the cows in the meadows looked different. And I realized we’ve worked on the subject a lot over the years, but we’ve never connected the dots. It has sort of been sublimated.”

In the mock-up of the book, images of luxuriously renovated country houses and migrant teenagers in dark shades are juxtaposed with pictures of homespun Russian peasants from a century ago. A chart shows the decline in farming over the past 150 years. In a ten-square-kilometer rural area outside Amsterdam, Koolhaas finds a solar panel vendor, bed and breakfasts, souvenir shops, a relaxation center, a breast- feeding center and a sculpture garden scattered amid land that is farmed mostly by Polish workers. Robots drive tractors and milk cows.

Koolhaas says the book will touch on a vital theme: how to come to terms with the relentless pace of modernization. The countryside has become “more volatile than the accelerated city,” Koolhaas writes in one of the mock-ups. “A world formerly dictated by the seasons is now a toxic mix of genetic experiment, industrial nostalgia [and] seasonal immigration.”

It’s hard to know whether you regard this as nightmare or opportunity, I tell him. “That has been my entire life story,” Koolhaas said, “Running against the current and running with the current. Sometimes running with the current is underestimated. The acceptance of certain realities doesn’t preclude idealism. It can lead to certain breakthroughs.” In fact Koolhaas’ urbanism, one could say, exists at the tipping point between the world as it is and the world as we imagine it.