Why Shakespeare is Julie Taymor’s Superhero

For the renowned director of the screen and stage, the Bard is a fantasy and a nightmare

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Taymor-ingenuity-portrait-631.jpg)

For such a physically slight, ballerina-like figure, Julie Taymor is metaphysically fierce. The fact that she arrives at our rendezvous in a New York bistro buzzing with adrenaline, having just come from the first rehearsal of her new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, only intensifies the impression. She’s on a Shakespeare high, and her enthusiasm for the relevance of Shakespeare is contagious.

Most of the world knows Julie Taymor as the director of The Lion King, the epic, viral Broadway smash that has circled the globe. It’s become a modern myth, virtually Homeric. A wild spectacle that, as she puts it, “got to the DNA” of a vast audience and wrapped their double helixes around her finger.

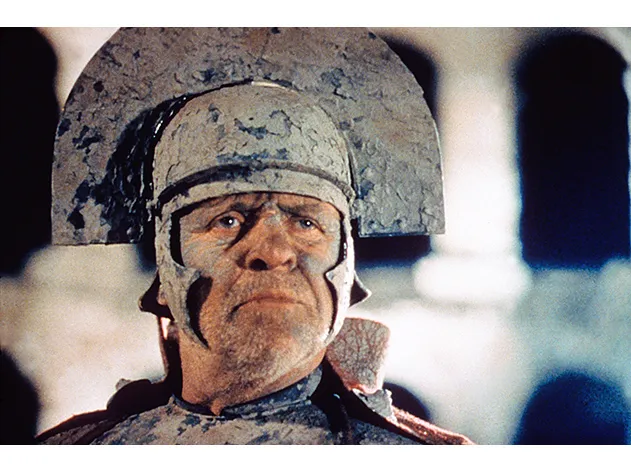

But there’s another Julie Taymor, lesser known and more surprising: the one who took one of Shakespeare’s most obscure, most brutal, haunting and mystifying tragedies—Titus Andronicus—and turned it into one of the greatest Shakespearean films ever. She made Titus in 1999 on a big budget with Anthony Hopkins playing the tragic title character and Jessica Lange playing Tamora, Queen of the Goths. Taymor took what had seemed to me a play that was a bit stilted on the page and blew it up into a magnificent Fellini/Scorsese fusion of raw bloody Shakespearean fury.

I’m not exaggerating: I watched it again recently at a screening at the Museum of Modern Art and felt like I had been given a metaphysical punch to the gut. I say this as someone who has watched virtually every major Shakespearean film in the course of writing a book on Shakespearean scholars and directors. Titus creates an intensity so breathtaking it makes you forget the rest of the world.

It made me rethink human nature, made me rethink Shakespeare’s nature. How could he have harbored such a horrific and merciless vision so early (he wrote Titus Andronicus when he was not yet 30, at least six years before Hamlet).

It also made me rethink Julie Taymor’s nature. How could the person who created The Lion King, with the theme of “The Circle of Life,” also create a Titus, which might well be called “The Circle of Death”? My mission, I decide even before meeting her, is to get people to see Titus and recognize just how utterly contemporary and relevant it is to the war-torn, terror-ridden world we live in today.

“It was massive!” I say to her as we sit down.

“It was massive!” she agrees. “My first feature. And it was so exciting.”

She takes a sip of prosecco. She reminds me of that line in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Though she be but little, she is fierce!” (Well, she’s not that little, but she radiates furious, focused energy.) The wild stories she tells in the big book about her work, aptly titled Playing With Fire, testify to that ferocity: about her time on a fellowship in Indonesia, putting together a theater troupe in the wild outback of Bali, daring the fires of live volcanoes, developing the unique Javanese and Balinese-influenced huge-mask-and-giant-puppet-based theater art that eventually made The Lion King such a spectacle.

I asked her what it’s like to direct Shakespeare, “It seems like the greatest thing for a human being—” I started to say.

“Oh, it’s the best!” she declares with utter finality. “I love to do musicals and operas, but that’s because they take you to another plane of existence. But for me Shakespeare is the most challenging. He’s the most far-out, the most wicked and spiritual, and demonic and philosophical. In one play!”

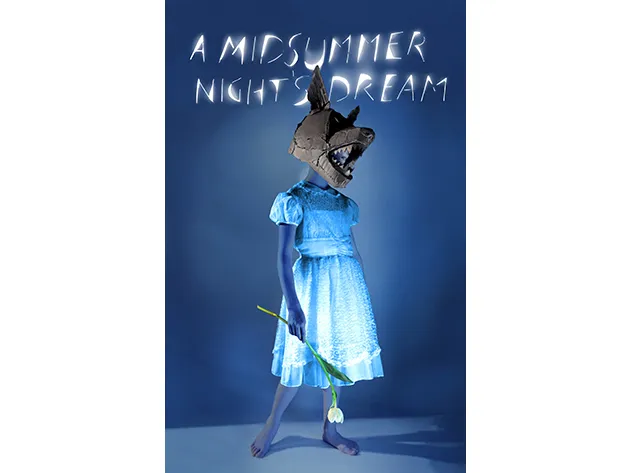

Of course Titus is not the only Shakespeare Taymor has done. She’s directed four versions of The Tempest, the last a brilliant film featuring Helen Mirren playing “Prospera,” the traditionally male Prospero role, in an extraordinarily revealing way. And now she’s doing A Midsummer Night’s Dream off Broadway.

She describes for me her primal experience with Shakespeare’s Dream.

“I remember being at Oberlin College and taking a bus 15 hours with my fellow schoolmates to New York to see Peter Brook’s Dream,” she says. It was a historic production, a production I also saw, that changed the way Shakespeare was done on both sides of the Atlantic.

“It had a powerful effect on me. And I don’t think I’ve seen a good one since, so I’ve pretty much avoided it for years. Partly because after The Lion King I did Titus and that’s the natural way to go—you do The Lion King and then you do Titus.” Circle of Life, Circle of Death.

“A bare stage—” I began to describe Brook’s set design, a kind of luminescent white box.

“Not a bare stage,” she counters. “The Globe [Shakespeare’s main venue] was a bare stage. It’s interesting because the Brook was revolutionary for our time, but not really for Shakespeare’s day, because in Shakespeare’s day it was just an empty stage and empty space—and you used your imagination.”

She tells me she’s devised a different kind of box for her Dream stage.

“The audience is on three sides and it’s basically a magic black box, like a Japanese lacquered black box, that has holes and windows and traps. But we’re using the idea there’s a prologue which is a bed.”

A bed as a prologue?

“This character [who turns out to be Puck, the chief instigator of mischief among the lovers in the play] is sleeping in a bed and from out of the earth trees push the mattress up and it floats, and then the bedsheets get attached and the mechanicals—the real mechanicals, my workmen—pull out the sheet and it becomes a canopy which becomes the sky. What I’m trying to do is what I think the play does so brilliantly—it goes from the poetic to the mundane, from the magical to the banal, kind of gossamer and intangible to the concrete and, you know, gaudy and real.”

She speaks almost as if possessed.

“It’s earthiness and concrete,” she goes on, “it’s there, you can touch it. A person sleeping in a bed dreams...trees grow, the bed floats, then these kind of New York guys come out and attach a hook and you see them pulling a light circuit, they pull the bedsheet up and it’s a sky! It’s a sky!”

The bedsheet/sky she says is her “ideograph” for this production, a word she uses for an emblematic design element—the play is about love and sex, after all—and everything else in her visual scheme grows out of it. Taymor started off as a theater set designer and she’s always found her way into a play through visual concepts. (Her ideograph for The Lion King, she says, was the wheel, from the Circle of Life to the bicycles the antelopes rode.)

“So from the bed, they start to make the trestle table for the wedding,” she says. “They do what I feel we as humans do—we take nature, we take a tree, and we make chairs, we make tables, we make concrete things out of natural ones. So we’re constantly reforming and reshaping what is nature into something practical, mechanical, useful. Weddings, marriages are useful because they control our inner natures. They put boundaries and handcuffs on our natural instincts.”

She speaks about the spirituality she finds in her productions.

“There’s a certain point of divine spirit that is inexplicable. You either feel it or you don’t. It takes you to another level. It happened in The Lion King—people don’t know why they cry. They don’t know! Something in the art of it touched them in a deep DNA way. And I’ve been able to be involved in productions that have had that effect on me, on the performers, on the audience....”

She takes a breath.

“That’s what I strive for.”

And she finds it over and over again in Shakespeare. For instance, the eternal question of love at first sight, the bewitching focus of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “What does the play do with that? What do we learn?”

“We usually think that if we see with the eye, it’s superficial,” she says, “but in this play it’s kind of opposite. You can see with the mind or heart. That I find a tough concept that Shakespeare’s bringing out...that he’s on a whole other level of what ‘seeing’ and ‘loving’ means.”

“Do you mean he sees love at first sight as something arbitrary?”

“Not always.” She starts talking about one of the two pairs of mixed-up young lovers in the play, Lysander and Hermia. She has an interesting insight into their relationship. In most of the criticism I’ve read about the play, the fact that Hermia loves Lysander and not Demetrius (whom Egeus, her father, wants her to marry) is arbitrary. I’ve seen the two male ingénues dressed identically in some productions to emphasize the point—affection is willy-nilly, arbitrary, impossible to predict—or faithfully sustain.

She’s read this too in her research, she says, but she begs to differ: “Are they out of their minds?! These are extremely well-etched and differentiated characters. Lysander is like a hippie, a poet. He’s not loved by Egeus [the father] because he is an artist. And that’s what little Hermia falls in love with. Demetrius is Wall Street....They’re unbelievably opposite.”

Lysander and Hermia go into the forest and Puck mistakenly puts drops of the play’s love potion in Lysander’s eyes, a potion made from the distillation of a flower called “love in idleness.”

“It’s a psychedelic!” Taymor exclaims. “The humor is obviously with the herb, because when Lysander wakes up with the drops in his eyes, he just dumps Hermia and easily falls in love with Helena, the first person to cross his path. But it’s not a true love, is it?”

“A potion is a juice, but the emotions—” I start to say.

“The emotion is unleashed!” she says, “and I think that Shakespeare’s saying that’s how easily we can switch our passions. A little thing can do it. Whether it’s love juice, a psychedelic drug or somebody swishes by in a different way—that love is extremely fickle. I think a lot of this is about all different levels of love, just like Titus is about every single aspect of violence.” Circle of Love. Circle of Death.

This brings her to a hole she’s spotted in the plot. It involves Demetrius, the Wall Street type, who is spurned by Hermia but loved by Helena, whom he spurns. Until, Taymor says, he wakes up with the juice in his eyes and says, “‘And now Helena who I always loved’ and you have to think—he’s on a drug.”

But she says, unlike the other youth—the poetic Lysander who gets the antidote for his drug and switches his affections back from Helena to Hermia—Demetrius “never gets off the drug,” Taymor says. “Because at the end [Shakespeare] didn’t take the drug off,” Taymor says. Perhaps he didn’t have the time. Or he forgot. “He probably wrote it over a weekend,” she says.

“Demetrius is still in love with Helena. We have no idea if he had an antidote to the drug or that the drug didn’t wear off and he found his true self.”

In other words this “hole,” this apparent neglect by Shakespeare to tell us what happened to Demetrius—is he still juiced or has he found a new truth—ends up posing the question at the center of the play: What is one’s true self, what is true love? How do

we know?

“There are many things in this play, more than other Shakespeare that I’ve directed, where we have to decide what we feel about it, it’s not answered in the play.”

So where does that leave love at first sight?

“I don’t think he believes in love at first sight,” she says.

She starts singing lyrics from a Beatles song, “Would you believe in a love at first sight / Yes I’m certain that it happens all the time.”

Which reminds me—it’s so hard to keep track of everything this woman has done—that she directed a movie, Across the Universe, that was a surprisingly moving adaptation of a slew of Beatles songs, a project she made with her longtime collaborator and significant other, Elliot Goldenthal.

And yes there was a much-praised film she directed about Frida Kahlo the artist and feminist icon of the ’30s and ’40s. And a number of operas and, oh yes, there was Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. The ambitious big budget Broadway superhero extravaganza that she collaborated on with Bono and The Edge, until “creative differences,” as they say, ended up with her leaving the production after two months of previews and some contentious litigation that has finally been settled, terms undisclosed. She said she just wouldn’t talk about it. Let’s face it: Shakespeare is her real superhero, not some spider.

I returned to the question that preoccupied Shakespeare—and her—throughout their careers. The nature of love and love at first sight.

“Was it love at first sight between you and Elliot?” I ask her.

“No, we worked together five years. So it wasn’t ‘some enchanted evening.’ [It’s been] 30 years now. But it was love at first sight as collaborators,” she says. “I love working with him. He’s a genius!”

Especially working on Shakespeare, she says. “We eat dinner going, ‘Oh my god, can you believe this piece of Shakespeare?’ this line, that line—so it continually feeds you to do Shakespeare because you’re always discovering something new.”

How many people still feel this way about Shakespeare after 400 or so years? I recall a dinner I had with the founder of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Sir Peter Hall, when he said he was worried that people were losing their grip on Shakespearean language.

“Are you kidding?” Taymor says. “What are there now, seven, ten productions going on in this city?”

And it is true. The New York Times has called it a “feast of Shakespeare.”

“There’s nobody in the Western world as good,” she explains. “Look at the movies being made that are either direct Shakespeare or adaptations of Shakespeare. ‘House of Cards’ is a complete Richard III revival.”

I ask if the “feast of Shakespeare” has something to do with the sense of being out of control—chaos at home, terror spreading around the world—and the need for wisdom and perspective from the Bard.

She doesn’t think so. She sees it more practically, as “a dearth of good writing for the stage” because many of the best writers are doing quality long-form TV. In addition, she says people have gotten over the idea that British Shakespeare is somehow more stodgy. (Many of the “feast of Shakespeare” productions are British imports.)

“Was there something about our situation today that makes Shakespeare more relevant?” I ask Jeffrey Horowitz, the founder of the Theatre for a New Audience, who put on the stage version of Taymor’s Titus back in 1994 and is highly regarded in his own right as a Shakespeare producer/director and thinker. He’s also a producer of her new Dream.

He thought it might have something to do with “America as a struggling empire. When Shakespeare wrote,” he pointed out, “England was dealing with the question of what it means to be English, and what political system should we have? America is losing its uncontested power in the world. Shakespeare is a writer who expresses an understanding of wrenching change and loss.”

Of course, he adds, there is also the star factor: “American stars playing Shakespeare—Al Pacino, F. Murray Abraham, Kevin Kline, Meryl Streep, Liev Schreiber, Ethan Hawke—all have great skills with Shakespeare and build audiences.”

The Shakespeare plays revived today, though, are mainly familiar ones—Romeo, Hamlet, Macbeth, even Taymor’s own Midsummer Night’s Dream. It had been Taymor’s daring to reach outside the famous Shakespeare plays and revive Titus (now available on YouTube as well as DVD). I say daring not just because it’s relatively obscure, but also because it’s so bloody and terrifying. Titus is the story of a Roman general, Titus Andronicus, who ends up in a death spiral of murder, mutilation, rape and the most grisly revenge in the history of revenge.

“How do you explain all this—?” I start to ask about the sensational, horrific material.

“I think that part of civilization—similar to Midsummer—is to harness the darker aspects of our nature. When you come to Tamora...”

Tamora is the queen of the conquered Goths, whose son is slaughtered in front of her by Titus.

“When Tamora sees her firstborn murdered, she says, ‘Cruel, irreligious piety.’”

For Taymor, these are “the most extraordinary three words. They represent our day and age better than any I know. Because it is [filled with] ‘cruel, irreligious piety’—in the name of which we bomb these people or we kill those people.

“My favorite play is Titus and it will always be Titus,” she says. “I think it contains the truth of human nature. Especially about evil, about violence, about blood. It investigates every aspect of violence that exists. It is the most terrifying play or movie that exists.”

When I ask why, she gives a terrifying answer:

“Because what Shakespeare’s saying is that anybody can turn into a monster. That is why I think Titus is way beyond Hamlet."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)