When a little Maltese named Cherry died of old age in 1881 at home in London, the dog’s owners were at a loss for what to do with the remains. At that time in the city, there were only a few options for disposing of a deceased pet’s body: throw it into the River Thames, toss it out with the rubbish or take it to a rendering plant to be turned into glue or fertilizer.

None of these options was acceptable to Cherry’s family, so they did something unheard of: They asked the gatekeeper of nearby Hyde Park, known as Mr. Winbridge, if they could bury their dog in his cottage’s garden, next to the park’s Victoria Gate entrance. Rather than scoff at this unusual request, Winbridge agreed. The family gathered for a short funeral and then laid their beloved friend to rest under a headstone simply inscribed, “Poor Cherry. Died 28 April 1881.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/74/08/7408af33-c69b-4b65-a7e5-57e5bf935858/london_hyde_park_5.jpg)

Cherry’s family likely had no idea, but they had just committed a “revolutionary act,” says Paul Koudounaris, a historian, author and photographer who specializes in death and cats. Although household pets had become increasingly common for 19th-century city dwellers in London and other European metropolises, until Cherry was laid to rest, urban animal companions had not received dignified burials there.

News of Cherry’s grave quickly spread around London, first by word of mouth and then through the media. Other bereaved and yard-less pet owners began showing up at Winbridge’s door, imploring the groundskeeper to allow them to lay their dog or cat to rest, too. Within a couple years, the garden was cluttered with headstones. It had become the first known urban pet cemetery in the world.

“Until then, it was considered eccentric to care so much about an animal that you would bury it,” Koudounaris says. But with the creation of the Hyde Park pet cemetery, there came “a strength and unity that suddenly makes people begin to think that it isn’t that weird to care about pets this much.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/be/79/be79a547-10d1-400d-9183-d47549f3a5be/bolivia_la_paz.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/0e/bb0e212f-f816-435e-8251-3a0139c6d7ee/bali_denpasar.jpg)

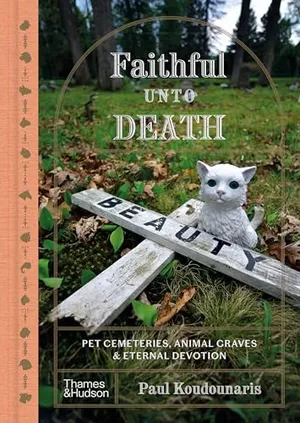

The Hyde Park pet cemetery still exists today. But its pivotal place in history is only made clear in Koudounaris’ new book, out on October 1: Faithful Unto Death: Pet Cemeteries, Animal Graves and Eternal Devotion. The book, which Koudounaris worked on for more than a decade, presents the first overarching account of pet cemeteries around the world. More than just a history, though, Koudounaris hopes that the book is “helpful to people in mourning for pets by providing examples of how other people have loved and lost.”

Faithful Unto Death: Pet Cemeteries, Animal Graves and Eternal Devotion

The remarkable stories of beloved pets―from the famous and unusual to the everyday―memorialized at burial sites around the world, accompanied by a rich selection of archival photos and the author's evocative images of their final resting places.

Koudounaris’ own interest in pet cemeteries was sparked in 2013, when a friend suggested he visit the Los Angeles Pet Memorial Park for a photography excursion. He thought he’d be there for an hour but wound up staying the entire day.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/d0/91d05d46-c7bb-4b9c-b51f-62adb3c0fd15/new_york_hartsdale_3.jpg)

His research took him to archives and pet cemeteries around the world, from Bolivia to Thailand. He visited a cemetery in Alabama dedicated solely to coonhounds, saw memorials for famous animals such as Toto (real name Terry) from The Wizard of Oz, and documented the grave of a French honeybee erected to raise awareness about pesticide poisoning. Everywhere he went he took photos, dozens of which are included in his book.

Part of Koudounaris’ research also entailed spending a year as a volunteer grief counselor for people who had lost their pets. This experience was extremely difficult emotionally, he says, but he felt it was necessary to better understand pet grief from other people’s perspectives. “There were some days where I could do just a little bit of work, because it could get so painful,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons this book took so long.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5e/18/5e18050f-7ad5-4423-b5d8-37b85c263279/helsinki_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/50/48500f0c-982b-4b69-9849-5df6f04297e4/juarez_2.jpg)

Early in the research process, Koudounaris knew he would be focusing on modern pet cemeteries, starting with the one in Hyde Park. While people have been burying animals throughout recorded history, Koudounaris makes a distinction in that many of these animals—such as the cats of ancient Egypt—were raised to be sacrificed. Others that received burials and grave markers, such as Alexander the Great’s favorite hunting dog, Peritas, were exceptional cases.

It was only in the 19th century that the modern phenomenon of pet ownership emerged. As people moved to cities in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, many adopted a new form of the rural tradition of animal-keeping by bringing a dog or cat into the home. “For the first time, you get people living in big cities with animals in confined quarters,” Koudounaris says. “This naturally changed the relationship people had with those animals—not just physically, but also emotionally.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ca/8a/ca8ac0c1-4c3b-4a55-b09e-63e92254d052/paris_1.jpg)

Society at large soon began to reflect this changing relationship. Dog breeds, especially of the smaller varieties, began to proliferate. The first dog-grooming salons opened in London, and in Paris, fashion designers began creating canine lines of clothing with accompanying look books. These cultural developments coincided with the rise of animal welfare organizations, starting in England with the 1824 founding of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The advent of pet cemeteries “went along with all these other revolutionary acts,” Koudounaris says. “They affirmed this idea that a pet that lived as a family member and that loved us and has been loved like a family member deserves a good death.”

After Cherry’s burial, pet cemeteries began to spread in the United Kingdom and Europe. But even as the idea of burying animals gained more acceptance, cemeteries created for this purpose were sometimes met with pushback. In 1899, for example, when the first public pet cemetery opened in the Paris area—complete with a potter’s field for animals—the Catholic Church expressed concern that it may too closely resemble a human cemetery. “To placate the Catholic Church, the cemetery owners had to make an agreement that there would not be any religious symbols on the graves,” Koudounaris says. Even today, he adds, he was unable to find any Christian iconography in the still-active Cimetière des Chiens.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a5/97/a5970f24-cca6-4224-8504-c39b6c4e739d/new_york_hartsdale_4.jpg)

In 1896, the first U.S. pet cemetery—which is also still active—opened in Hartsdale, New York, in Westchester County. From there, “this really became an American story,” Koudounaris says. “There are now more pet cemeteries in the United States than in the rest of the world combined, and there are a staggering number of different types.”

Around the U.S., Koudounaris found, for example, pet cemeteries dedicated to specific types of hunting dogs, to military pets and to police dogs. “What makes the United States so fascinating is there’s a polygenesis,” Koudounaris says. “While pet cemeteries are starting on the East Coast with the traditional European-type model, they’re also being born in a whole lot of other places in entirely different forms.”

Hundreds of official pet cemeteries are in operation around the country today, in all 50 states. But Koudounaris was especially fascinated by the “off-the-grid desert pet cemeteries,” he says—the ones that aren’t listed in official registries. In Arizona and Utah, for example, he visited dog graveyards at late 19th- and early 20th-century mining settlements, and in Nevada, he found an old burial plot for horses. Unlike in the Northeast, out West, there “really were no regulations being enforced,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3f/e4/3fe4038f-86ac-46af-a976-e48d888735c6/california_bishop_3.jpg)

That pioneer model of pet burial, complete with white picket fencing, still continues to some extent today. In California, Nevada, Arizona and Colorado especially, Koudounaris often came across unlisted pet cemeteries that contained all-homemade grave markers. “These places are kind of the Art Brut of mourning: It’s normal, everyday people looking for a way to express, in their own terms, what they feel,” Koudounaris says. He’s seen grave markers take forms as varied as fire hydrants, painted animal portraits and mailboxes in which owners leave little notes or treats for their pets. “Sometimes it’s very elaborate, and sometimes it’s just a small statement,” he says. Always, though, “it’s so personal, and it’s so intimate.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c8/18/c81811e6-0947-4187-b4ec-99523943e142/arizona_ajo.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/95/94/95944527-ecea-426f-923b-036ce55dfdfe/california_bishop_1.jpg)

Ultimately, Koudounaris wrote his book to provide a comforting testament to pet owners everywhere that they are not alone in their grief, no matter how profound. “It’s really a universal experience to love an animal, but it’s still something we don’t really talk about,” he says. “There’s this stigma of, ‘It’s only an animal.’”

This tension is reflected in a common inscription that he often saw on pet graves around the world: “Only a cat” or “Only a dog.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/2b/372b8e09-5488-4e88-8f0c-b094c2837d2b/massachusetts_dedham.jpg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1000x652:1001x653)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0e/83/0e836c95-20cb-4f96-88e5-09f044a70bf1/london_hyde_park_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)