Willem de Kooning Still Dazzles

A new major retrospective recounts the artist’s seven-decade career and never-ending experimentation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Willem-de-Kooning-631.jpg)

In 1926, Willem de Kooning, a penniless, 22-year-old commercial artist from the Netherlands, stowed away on a freighter bound for America. He had no papers and spoke no English. After his ship docked in Newport News, Virginia, he made his way north with some Dutch friends toward New York City. At first he found his new world disappointing. “What I saw was a sort of Holland,” he recalled in the 1960s. “Lowlands. What the hell did I want to go to America for?” A few days later, however, as de Kooning passed through a ferry and train terminal in Hoboken, New Jersey, he noticed a man at a counter pouring coffee for commuters by sloshing it into a line of cups. “He just poured fast to fill it up, no matter what spilled out, and I said, ‘Boy, that’s America.’”

That was de Kooning, too. Of the painters who emerged in New York during the late 1940s and early ’50s—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, among them—de Kooning, who died in 1997, remains the most difficult to capture: He is too vital, restless, jazzy, rude and unpredictable to fit into any one particular cup. He crossed many of art’s boundaries, spilling between abstraction and figuration over a period of 50 years—expressing a wide variety of moods—with no concern for the conventions of either conservative or radical taste. According to Irving Sandler, an art historian who has chronicled the development of postwar American art, it was de Kooning who “was able to continue the grand tradition of Western painting and to deflect it in a new direction, creating an avant-garde style that spoke to our time.”

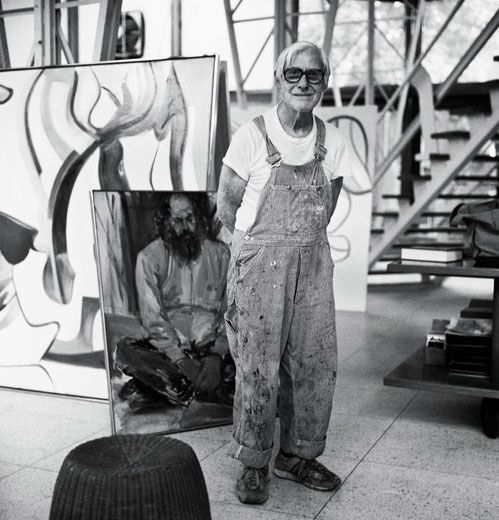

The de Kooning retrospective that opened last month at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)—the first devoted to the full scope of the artist’s seven-decade career—presents a rich, nuanced view of a great American painter. For curator emeritus John Elderfield, who organized the show, the endeavor was unusually personal: the allure of de Kooning’s art helped lead the English-born Elderfield to settle in America. He argues that de Kooning is a painter of originality who invented a new kind of modern pictorial space, one of ambiguity. De Kooning sought to retain both the sculptural contours and “bulging, twisting” planes of traditional figure painting, Elderfield suggests, and the shallow picture plane of modernist art found in the Cubist works of, for example, Picasso and Braque. De Kooning developed several different solutions to this visual issue, becoming an artist who never seemed to stop moving and exploring. He was, in his own enigmatic turn of phrase, a “slipping glimpser.”

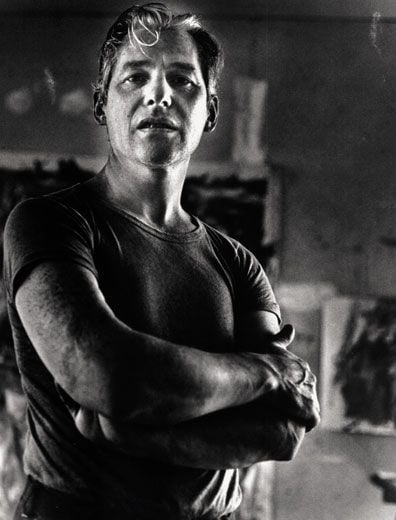

During the ’50s de Kooning became the most influential painter of his day. “He was an artist’s artist,” says Richard Koshalek, director of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum, which has one of the largest collections of de Kooning’s work. “He had a great impact on a very wide range of artists.” Brice Marden, a painter who was the subject of a 2006 MoMA retrospective, agrees: “You were brought up on de Kooning. He was the master. He was the teacher.” To many he was also a romantic figure with movie-star looks and an existential swagger, as he drank at the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village with Pollock and moved from love affair to love affair.

Despite his success, de Kooning eventually paid a price for his unwillingness to follow the prevailing trends. His ever-changing art—especially his raucous depiction of women—was increasingly slighted by critics and art historians during his lifetime. It did not, Elderfield suggests, “fit easily with those works thought to maintain the familiar modernist history of an increasingly refined abstraction.” The curators at MoMA itself tended to regard de Kooning after 1950 as a painter in decline, as evidenced by the museum’s own collection, which is considerably stronger in Pollock, Rothko and Newman than in de Kooning.

The quarrel has ended: The current retrospective makes amends. De Kooning’s range now looks like a strength, and his seductive style—“seductive” is the appropriate word, for his brush stroke is full of touch—offers a painterly delight rarely found in the art of our day.

De Kooning grew up near the harbor in tough, working-class Rotterdam. He seldom saw his father, Leendert—his parents divorced when he was a small boy—and his domineering mother, Cornelia, who tended a succession of bars, constantly moved her family in search of less expensive housing. She regularly beat him. Money was short. At the age of 12, he became an apprentice at Gidding and Sons, an elegant firm of artists and craftsmen in the heart of fashionable Rotterdam that specialized in design and decoration. He soon caught the eye of the firm’s owners, who urged him to take classes after work six nights a week at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts.

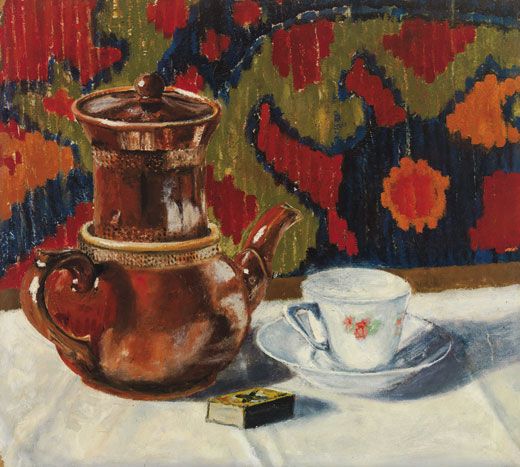

As a result, de Kooning received a strong grounding in both commercial design and the classical principles of high art. He was precocious; the retrospective at MoMA includes the remarkable Still Life (1917) he made at the Academy at the age of 13. He had to support himself, however. At the age of 16, de Kooning struck out on his own, circulating on the bohemian edges of Rotterdam and picking up jobs here and there. He also began to fantasize about America, then regarded by many in Europe as a mythical land of skyscrapers, movie stars and easy money—but not, perhaps, of art. When he stowed away on the freighter, de Kooning later recalled, he did not think there were any serious artists in America.

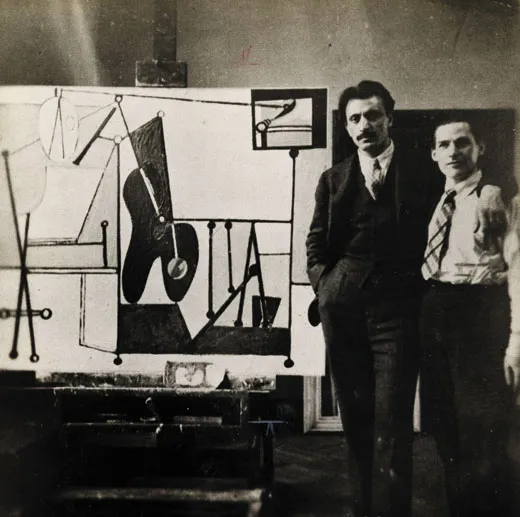

In his first years in America, initially in Hoboken, New Jersey, and then in New York, he lived much as he had in Rotterdam, finding work as a commercial artist and occasionally painting in his spare time. He found that there were, in fact, serious artists in America, many of whom also took commercial jobs to survive. He began to spend his time in the coffee shops they favored in Chelsea and Greenwich Village, talking away the night over nickel cups of coffee. Almost everyone he knew was poor; the sale of a painting was rare. In this environment, the abiding commitment of certain artists—above all, the devotion of Arshile Gorky to the tradition of modernist painting—had a pronounced impact on de Kooning.

Gorky, an Armenian-born immigrant, had no patience for those who did not commit themselves unreservedly to art. Nor did he have time for those he deemed provincial or minor in their ambitions, such as those who romanticized rural America or attacked social injustice. (“Proletariat art,” Gorky said, “is poor art for poor people.”) In Gorky’s view if you were serious, you studied the work of modernist masters such as Picasso, Matisse and Miró, and you aspired to equal or better their achieve-ment. Contemporaries described Gorky’s studio on Union Square as a kind of temple to art. “The great excitement of 36 Union Square,” said Ethel Schwabacher, a student and friend of Gorky’s, “lay in the feeling it evoked of work done there, work in progress, day and night, through long years of passionate, disciplined and dedicated effort.”

Gorky’s example, together with the creation of the Federal Art Project, which paid artists a living wage during the Depression, finally led de Kooning to commit himself to being a full-time artist. In the ’30s, Gorky and de Kooning became inseparable; their ongoing discussions about art helped each develop into a major painter. De Kooning, struggling to create a fresh kind of figurative art, often painted wan, melancholy portraits of men and, less frequently, women. He worked and reworked the pictures, trying to reconcile his classical training with his modernist convictions. He might allow a picture to leave his studio if a friend bought it, since he was chronically short of cash, but he discarded most of his canvases in disgust.

In the late ’30s, de Kooning met a young art student named Elaine Fried. They would marry in 1943. Fried was not only beautiful, her vivacity matched de Kooning’s reserve. Never scrimp on the luxuries, she liked to say, the necessities will take care of themselves. One of her friends, the artist Hedda Sterne, described her as a “daredevil.” “She believed in gestures without regret, and she delighted in her own spontaneity and exuberance,” Sterne said. “I was a lot of fun,” Elaine would later recall. “I mean, a lot of fun.” She also considered de Kooning a major artist—well before he became one—which may have bolstered his confidence.

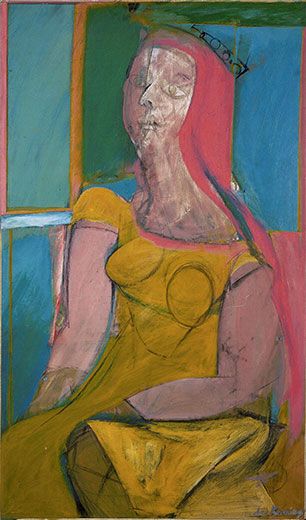

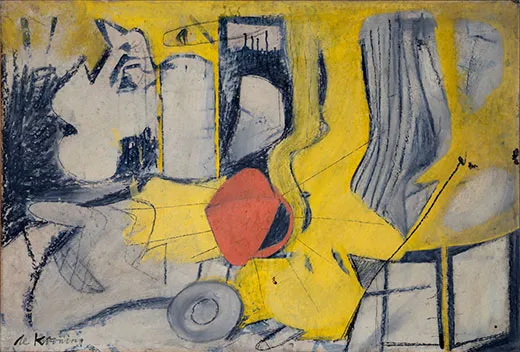

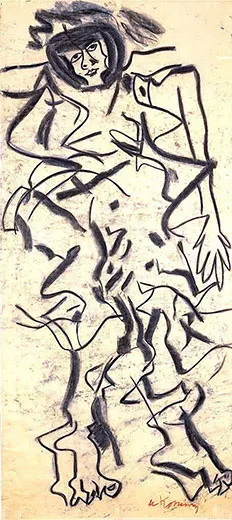

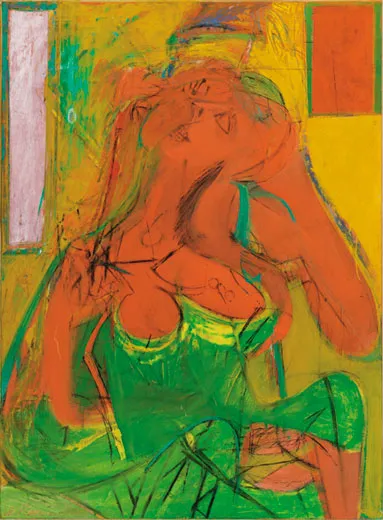

A fresh sensation of the female figure, no doubt inspired by Elaine, began to course through de Kooning’s art. The color brightened. Boundaries fell away. He no longer seemed constrained by his classical training: the women in the paintings now threatened to break out and break apart; distinguishing figure from ground became, in places, difficult. The artist was beginning to master his ambiguous space. It seemed natural that de Kooning, who instinctively preferred movement to stillness and did not think the truth of the figure lay only in its surface appearance, would begin shifting along a continuum from the representational to the abstract. Yet even his most abstract pictures, as de Kooning scholar Richard Shiff has observed, “either began with a reference to the human figure or incorporated figural elements along the way.”

De Kooning’s move in the late ’40s toward a less realistic depiction of the figure may have been prompted, in part, by the arrival in the city earlier in the decade of a number of celebrated artists from Paris, notably André Breton and his circle of Surrealists, all refugees from the war. De Kooning was not generally a fan of Surrealism, but the movement’s emphasis on the unconscious mind, dreams and the inner life would have reinforced his own impatience with a purely realistic depiction of the world. The Surrealists and their patron, the socialite Peggy Guggenheim, made a big splash in New York. Their very presence inspired ambition in American artists.

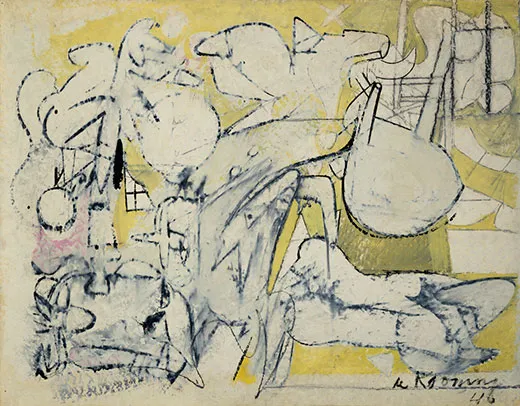

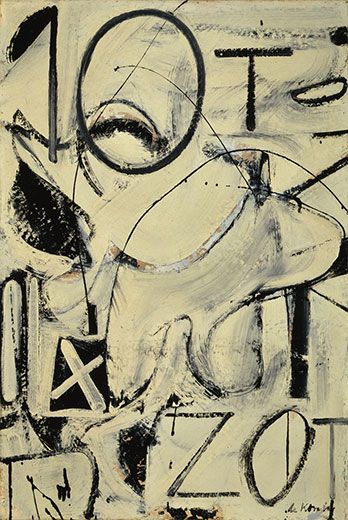

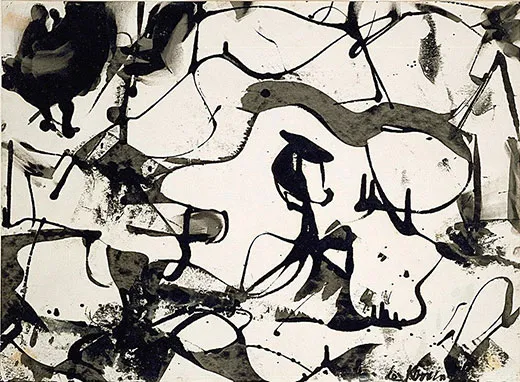

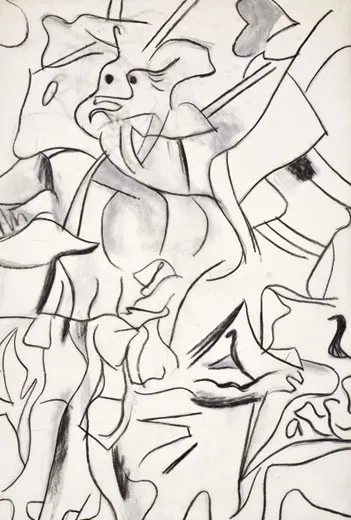

Still, de Kooning remained on the margins. The Federal Art Project no longer existed and there was little to no market for modern American art. It was in this dark period that de Kooning began his great series of black-and-white abstractions. He and his close friend, the painter Franz Kline, unable to afford costly pigments, famously went out one day and bought inexpensive black and white enamel household paint and (according to legend) with devil-may-care abandon began turning out major works. It was not, of course, that simple. De Kooning had labored for many years to reach this moment; and, in a way, the moment now found him. The horror of World War II—and accounts of the Holocaust coming out of Europe—created a new perception among de Kooning and some American artists of a great, if bleak, metaphysical scale. (They also had before their eyes, in MoMA, Picasso’s powerful, monochromatic Guernica of 1937, his response to the fascist bombing of the Spanish city.) In contrast to their European contemporaries, the Americans did not live among the war’s ruins, and they came from a culture that celebrated a Whitmanesque boundlessness. De Kooning, whose city of birth had been pounded into rubble during the war, was both a European and an American, well positioned to make paintings of dark grandeur. In 1948, when he was almost 44, he exhibited his so-called “black and whites” at the small and little-visited Egan Gallery. It was his first solo show. Few pictures sold, but they were widely noticed and admired by artists and critics.

It was also in the late 1940s that Jackson Pollock began to make his legendary “drip” abstractions, which he painted on the floor of his studio, weaving rhythmic skeins of paint across the canvas. Pollock’s paintings, also mainly black and white, had a very different character from de Kooning’s. While generally abstract, de Kooning’s knotty pictures remained full of glimpsed human parts and gestures; Pollock’s conveyed a transcendent sense of release from the world. The titles of the two greatest pictures in de Kooning’s black-and-white series, Attic and Excavation, suggest that the artist does not intend to forget what the world buries or puts aside. (De Kooning no doubt enjoyed the shifting implications of the titles. Attic, for example, can refer to an actual attic, suggest the heights of heaven or recall ancient Greece.) Each painting is full of figurative incident—a turn of shoulder here, a swelling of hip there, but a particular body can be discerned in neither. “Even abstract shapes,” de Kooning said, “must have a likeness.”

De Kooning completed Excavation, his last and largest picture in the series, in 1950. The director of MoMA, Alfred Barr, then selected the painting, along with works by Pollock, Gorky and John Marin, to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale—a signal honor for all four American modernists. Journalists began to take notice. Pollock was the subject of a photo spread in Life magazine in 1949. The light of celebrity was beginning to focus on what had been an obscure corner of American culture. The Sidney Janis Gallery, which specialized in European masters, now began to pitch de Kooning and other American artists as worthy successors to Picasso or Mondrian. Critics, curators and art dealers increasingly began to argue that where art was concerned, New York was the new Paris.

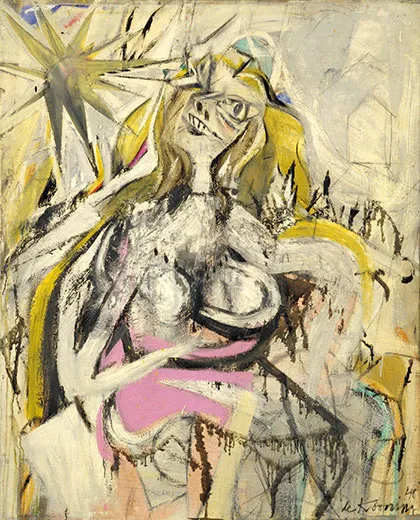

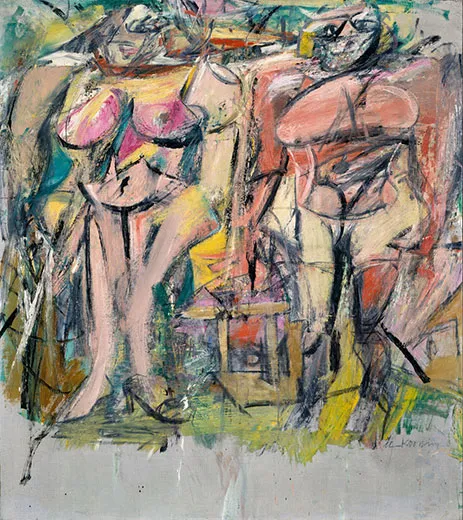

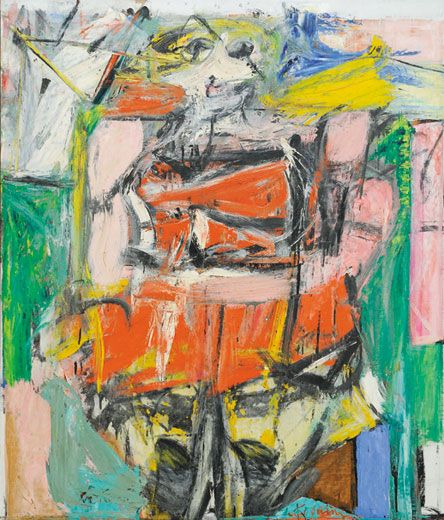

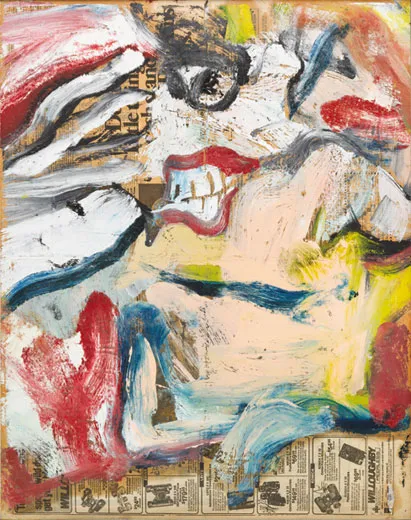

By the early ’50s, De Kooning was a painter of growing renown with a blue-chip abstract style. Most of his contemporaries believed he would continue to produce paintings in that style. But in one of the most contrary and independent actions in the history of American art, he gave up his black-and-white abstractions to focus mainly, once again, on the female figure. He struggled over a single canvas for almost two years, his friends increasingly concerned for his well-being as he continually revised and scraped away the image. He finally set the painting aside in despair. Only the intervention of the influential art historian Meyer Schapiro, who asked to see it during a studio visit, persuaded de Kooning to attack the canvas once again—and conclude that he had finished Woman I (1950-52). Then, in rapid succession, he completed several more Woman paintings.

De Kooning described Woman I as a grinning goddess—“rather like the Mesopotamian idols,” he said, which “always stand up straight, looking to the sky with this smile, like they were just astonished about the forces of nature...not about problems they had with one another.” His goddesses were complicated: at once frightening and hilarious, ancient and contemporary. Some critics likened them to Hollywood bimbos; others thought them the work of a misogynist. The sculptor Isamu Noguchi, a friend of de Kooning’s, recognized their ambivalence: “I wonder whether he really hates women,” he said. “Perhaps he loves them too much.” Much of the complication comes from the volatile mixture of vulgarity and a refinement in de Kooning’s brushwork. “Beauty,” de Kooning once said, “becomes petulant to me. I like the grotesque. It’s more joyous.”

Not surprisingly, de Kooning doubted that his show of recent work in 1953 would be successful, and the leading art critic of the time, Clement Greenberg, thought de Kooning had taken a wrong turn with the Woman series. Much to de Kooning’s surprise, however, the show was a success, not just among many artists but among a public increasingly eager to embrace American painting.

De Kooning suddenly found himself a star—the first celebrity, arguably, in the modern American art world. The only painter in the early ’50s of comparable or greater stature was Jackson Pollock. But Pollock, then falling into advanced alcoholism, lived mainly in Springs (a hamlet near East Hampton on Long Island) and was rarely seen in Manhattan. The spotlight therefore focused on de Kooning, who became the center of a lively scene. Many found him irresistible, with his Dutch sailor looks, idiosyncratic broken English and charming accent. He loved American slang. He’d call a picture “terrific” or a friend “a hot potato.”

In this hothouse world, de Kooning had many tangled love affairs, as did Elaine. (They separated in the 1950s, but never divorced.) De Kooning’s affair with Joan Ward, a commercial artist, led to the birth, in 1956, of his only child, Lisa, to whom he was always devoted—though he never became much of a day-to-day father. He also had a long affair with Ruth Kligman, who had been Pollock’s girlfriend and who survived the car crash in 1956 that killed Pollock. Kligman was both an aspiring artist who longed to be the muse to an important painter and a sultry young woman who evoked stars such as Elizabeth Taylor and Sophia Loren. “She really put lead in my pencil,” de Kooning famously said.

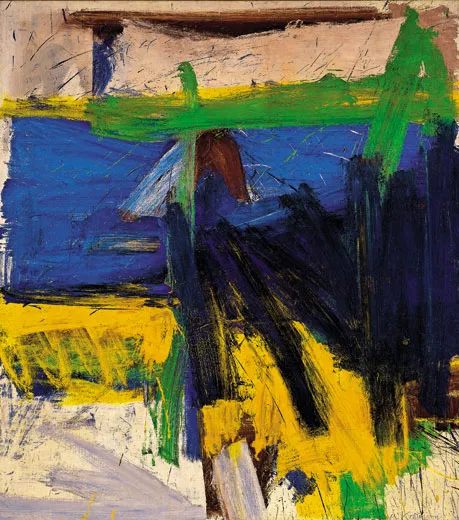

Following the Woman series, de Kooning developed a series of abstractions (the best known is Easter Monday) that capture the gritty, churning feel of life in New York City at mid-century. In the later ’50s, he simplified his brush stroke. Now, long broad swaths of paint began to sweep across the canvas. He was spending increasing amounts of time in Springs, where many of his friends had summer places. The pictures of the late ’50s often allude to the light and color of the countryside while containing, of course, figurative elements. Ruth’s Zowie (1957) has a kind of declarative élan and confidence. (Kligman provided the title when she entered de Kooning’s studio and, seeing the picture, exclaimed “Zowie!”) De Kooning himself never learned to drive a car, but he loved traveling the broad new American highways. In 1959 the art world mobbed the gallery opening of what is sometimes called his highway series: large, boldly stroked landscapes.

De Kooning was never entirely comfortable as a celebrity. He always remained, in part, a poor boy from Rotterdam. (When he was introduced to Mrs. John D. Rockefeller III, who had just bought Woman II, he hemmed and hawed and then blurted out, “You look like a million bucks!”) Like many of his contemporaries, he began drinking heavily. At the peak of his success toward the end of the 1950s, de Kooning was a binge drinker, sometimes disappearing for more than a week at a time.

In the ’50s, many young artists had imitated de Kooning; critics called them “second generation” painters—that is, followers of pioneers like de Kooning. In the ’60s, however, the art world was rapidly changing as Pop and Minimal artists such as Andy Warhol and Donald Judd brought a cool and knowing irony to art that was foreign to de Kooning’s lush sensibility. These young artists did not want to be “second generation,” and they began to dismiss the older painter’s work as too messy, personal, European or, as de Kooning might put it, old hat.

In 1963, as de Kooning approached the age of 60, he left New York City for Springs with Joan Ward and their daughter. His life on Long Island was difficult. He was given to melancholy, and he resented being treated like a painter left behind by history. He still went on periodic benders, which sometimes ended with his admission to Southampton Hospital. But his art continued to develop in extraordinary new ways.

De Kooning immersed himself in the Long Island countryside. He built a large, eccentric studio that he likened to a ship, and he became a familiar figure around Springs, bicycling down the sandy roads. His figurative work of the ’60s was often disturbing; his taste for caricature and the grotesque, apparent in Woman I, was also found in such sexually charged works as The Visit (1966-67), a wet and juicy picture of a grinning frog-woman lying on her back. In his more abstract pictures, the female body and the landscape increasingly seemed to fuse in the loose, watery paint.

De Kooning also began making extraordinarily tactile figurative sculptures: Clamdigger (1972) seemed pulled from the primordial ooze. The paintings that followed, such as ...Whose Name was Writ in Water (1975), were no less tactile but did not have the same muddiness. Ecstatic eruptions of water, light, reflection, paint and bodily sensation—perhaps a reflection, in part, of de Kooning’s passion for the last great love of his life, Emilie Kilgore—the paintings look like nothing else in American art. And yet, in the late ’70s, de Kooning abruptly, and typically, ended the series. The pictures, he said, were coming too easily.

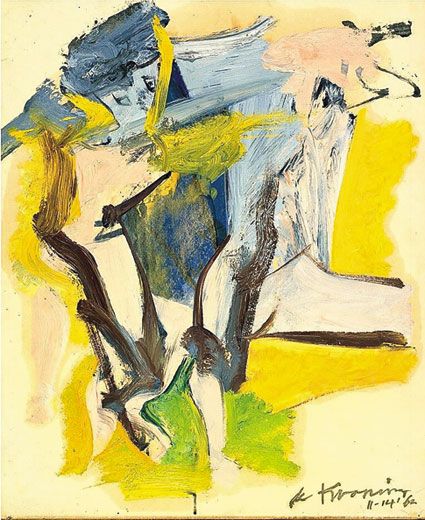

It was also in the late ’70s that de Kooning first began exhibiting signs of dementia. His wife, Elaine, who came back into his life at this time, began to monitor him carefully. Increasingly, as the ’80s wore on, he would depend on assistants to move his canvases and lay out his paints. Some critics have disparaged the increasingly spare paintings of this period. Elderfield, however, treats the late style with respect. In the best of the late works, de Kooning seems to be following his hand, the inimitable brush stroke freed of any burden and yet lively as ever. “Then there is a time in life,” he said in 1960, as he wearied of New York City, “when you just take a walk: And you walk in your own landscape.”

De Kooning died on March 19, 1997, at his Long Island studio, at the age of 92. He traveled an enormous distance during his long life, moving between Europe and America, old master and modernist, city and country. De Kooning’s art, said the painter Robert Dash, “always seems to be saying goodbye.” De Kooning himself liked to say, “You have to change to stay the same.”

Mark Stevens is the co-author, with his wife Annalyn Swan, of the Pulitzer Prize-winning de Kooning: An American Master.