Witnessing the Latino Experience at the American Art Museum

A voluminous new exhibition highlights Latino art as American art

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/USA-made-Smithsonian-hand-631.jpg)

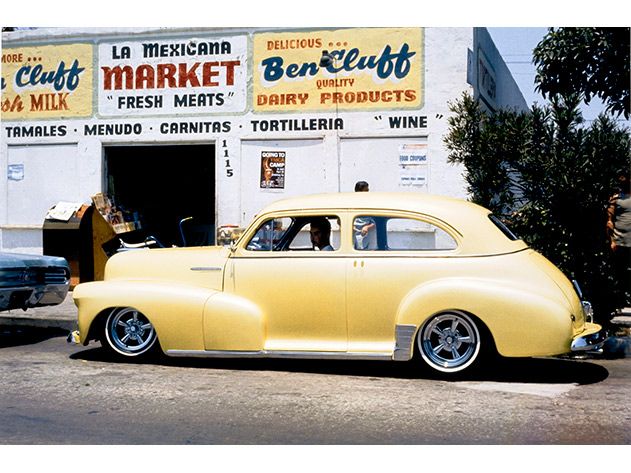

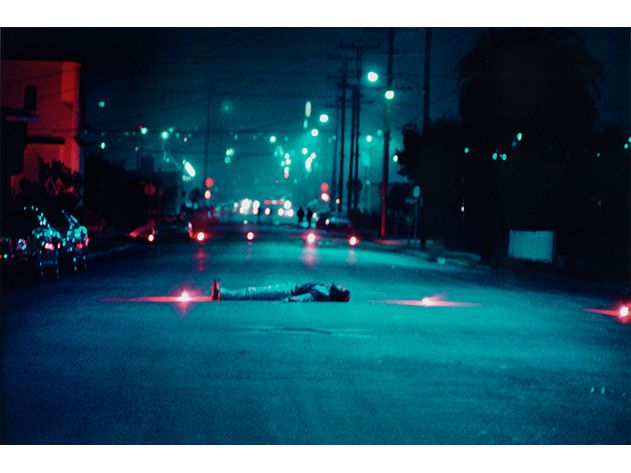

One day in 1987, Joseph Rodriguez was out taking photographs in Spanish Harlem. “It was a rough neighborhood then,” Rodriguez says. “There were a lot of drugs.” When he met a man he knew named Carlos, he asked, “Where is East Harlem for you?” Carlos spread his arm wide as if to take in all of upper Manhattan and said, “Here it is, man.” And Rodriguez took his picture.

Rodriguez’s project in Spanish Harlem was the prelude to his renown as a documentary photographer; he has produced six books, been collected by museums and appeared in magazines such as National Geographic and Newsweek. Now Carlos is among the 92 modern and contemporary artworks that make up “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art,” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through March 2, 2014. The 72 artists represented are of diverse descent—Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Dominican—but all of American residence, and their work dates from the 1950s to the present. The exhibition is a landmark event in its historical range, its pan-Latino breadth and its presentation of Latino art as part of American art. “‘Our America’ presents a picture of an evolving national culture that challenges expectations of what is meant by ‘American’ and ‘Latino,’” says E. Carmen Ramos, the museum’s curator of Latino art and the exhibition’s curator.

“My sense,” says Eduardo Diaz, director of the Smithsonian Latino Center, “is that mainstream arts and educational institutions have been too fearful, too lazy to mix it up with our communities and our artists and really dig deep into our histories, our traditions, our hybrid cultures.”

The mid-20th century was a turning point for Latino artists. “Many of them began attending art schools in the United States,” Ramos says. “It is also around mid-century that Latino communities begin to contest their marginalized position within American society,” prompting artists in those communities to refer to Latino culture and experience in their work.

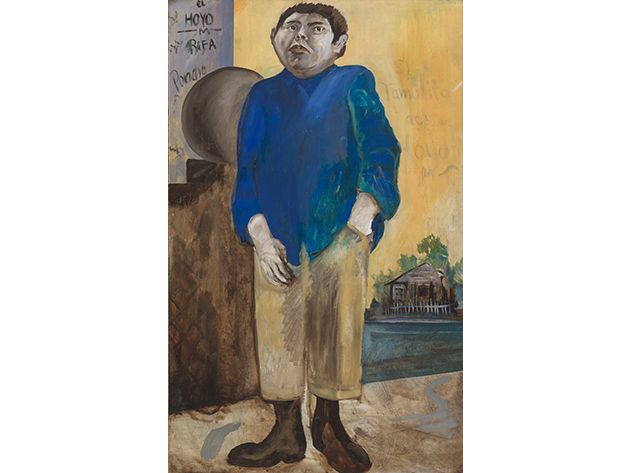

Take, for example, Roberto Chavez’s painting of a neighborhood boy, El Tamalito del Hoyo, from 1959 (left). “Chavez was a Korean War veteran who returned to Los Angeles and went to UCLA,” Ramos says. He belonged to a multi-ethnic group of painters who “developed a funky expressionism”; his portrait of the boy includes what Ramos notes are “high-water pants and old sneakers,” and skin color that blends in with the urban environment. “There’s a kind of implicit critique of the suburban dream” so prevalent in mainstream America in the 1950s, she says.

Rodriguez’s Carlos is more assertive—it appears in a part of the exhibition that explores art created around the civil rights movement. By then, Latinos “were insiders of the urban experience,” Ramos says. Carlos “conveys that sense of ownership of the city. You have that hand almost grabbing the city.”

Rodriguez, who lives in Brooklyn, doesn’t know what became of Carlos, but he is familiar with the dangers that come with urban poverty; as a young man, he struggled with drug addiction. “The camera is what saved me,” he says. “It gave me a chance to investigate, to reclaim, to re-envision what I wanted to be in the world.”

Diaz says, “In our supposedly post-racial society, ‘Our America’ serves to assert that the ‘other’ is us—U.S.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)