The Woman Who Built the Waldorf of the Catskills

Despite her humble origins, Jennie Grossinger learned to play the role of hostess

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/e9/7ee9a24d-8e24-4e52-9e57-f5380e75e5bf/u1072607-crop.jpg)

Just as in Casablanca, in which everybody went to Rick’s, so in the Catskill Mountains of New York, where everybody aspired to go to Jennie’s.

In its storied 72-year existence, Jennie Grossinger’s family boarding house had many names, including Longbrook House, Grossinger's Terrace Hill House, Grossinger's Catskill Resort Hotel (which built upon the original framework of the Terrace Hill House), and then finally, at the peak of its grandeur, just plain Grossinger’s (or, even better, simply the G). The press referred to the place as the “Waldorf of the Catskills.”

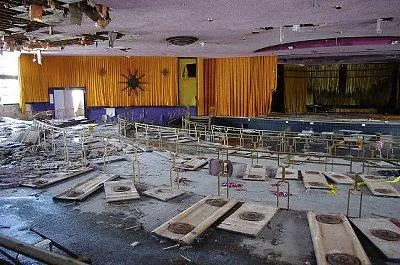

Grossinger’s eventual 1,200-acre, 35-building "Kingdom of Outdoor Happiness,” boasted indoor and outdoor Olympic-sized pools, its own ski slope, a summer ice rink, a dining room that seated 3,000, and a 24/7 staff that catered to every guest need, including matchmaking. It was the New York City escape to which all other Catskills operations—indeed, lodgings throughout America—aspired.

In the establishment’s post-World War II heyday, when it welcomed some 150,000 guests a year, it evolved into the prototype of a particularly successful version of American leisure—the everything-under-one-roof facilities that to this day take the form of Las Vegas hotels, Disney amusement parks and the international cruise line industry. And even if you don’t know Grossinger’s by name, you may be familiar with the cinematic sensation it inspired—1987’s Dirty Dancing.

In an era when America’s finer hotels and resorts freely discriminated against admitting Jews, and, in a gentlemen’s agreement with one another, even shared information about prospective guests with potentially Jewish-sounding names, the Catskills’ Borscht Belt—so named because of a favorite menu item—grew to rival anything a WASP enclave could offer. It had golf, tennis, even better food than could be found elsewhere (and more of it). It was a training ground for the fertile minds of show business, who filled resort showrooms with everything from lavish musicals to hilarious stand-up routines from comics who had yet to make a name for themselves, from Jerry Lewis to Jerry Seinfeld.

The Grossinger story in America started with Jennie’s father, Selig Grossinger, who had been a land overseer in Galatia, a part of the Austro-Hungarian, when he emigrated for America in 1897. After pressing pants on the Lower East Side of New York for three years, he sent steerage-class tickets for his wife, Malke, and their two young daughters, Jennie and Lottie. The family butcher shop, followed by a restaurant, failed. The restaurant had at least provided Malke a venue to show off her cooking, although the enterprise allegedly went belly up because she was too generous with her delicious portions. (Or so claimed Jennie Grossinger’s authorized biographer.) Better yet, the teenaged Jennie was able to hone her blossoming skills as a hostess and waitress on guests whose names she impressively always seemed to remember.

Selig’s health was failing as well; years of pants pressing over hot coals having taken their toll. A neighbor suggested buying land in the Catskills because, besides resembling Galatia, land was fairly cheap. In 1896, a sanitarium for treating tuberculosis (a constant threat on the Lower East Side, as well as the better neighborhoods of the city) had opened in the town of Liberty, New York. Its presence sent the wealthy WASPs who had long vacationed in the region fleeing and real estate prices plummeting.

Selig found a farm with a house on the outskirts of Liberty, in the Sullivan County town of Ferndale. The farm, like most in the Catskills, sat on soil that was too rocky to produce crops, and the house was ramshackle, despite the best efforts to patch up its holes by Malke and Jennie—who, since 1912, had been married to her cousin, Harry Grossinger, a salesman in the garment district.

The Grossinger house took in its first guest in 1914: Mrs. Carolyn Brown, originally from Romania but now from the Bronx, who observed from the traditional Orthodox Jewish wig worn by Malke that the family had to be religiously observant. Unhappy with her current accommodations in the Catskills, Mrs. Brown asked if she and her husband might board instead with the Grossingers. The Grossingers said yes, welcoming the first of the hundreds of thousands of those who would walk through their doors.

Throughout the resort’s long existence stood Jennie, a female, Jewish Horatio Alger. While her impoverished early years came back to haunt her—she was long treated for severe depression, a fact she kept well out of public view—she also strove to keep improving, both herself (she hired “an English professor, a Spanish teacher, a piano teacher, an elocution teacher, a literature teacher, a painting teacher—she learned how to guide a motorboat in the canals in Miami Beach,” said her daughter) and the business that bore her name. She inspected all the first-class hotels along the Eastern seaboard and then instituted their rules at her resort, such as jackets on gentlemen at dinner time—Grossinger’s, she insisted, was to be second to none.

Hers wasn’t an impersonal corporate institution, but a thriving component of American family life. “A resort isn’t the buildings and kitchens and lakes or nightclubs,” she said. “The real hotel is the people who work here.”

And that magic started at the top. The hotelier’s daughter, Elaine Etess, was struck by the fact that even though her mother left school in the fourth grade to support her family, she grew up "to hold her own with the first ladies of the United States. Eleanor Roosevelt was a dear friend of hers." As was Nelson Rockefeller, Cardinal Francis Joseph Spellman, and Eddie Fisher, who was not only discovered at Grossinger’s, but also honeymooned there with his first wife, Debbie Reynolds, before later bringing his second, Elizabeth Taylor. Jennie (whom everyone addressed by first name—just as Disney was called Walt) possessed, according to her daughter, an unpretentious “ease with people . . . She was as comfortable sitting at a head table as she was sitting in a chair in her living room.”

The ability to create a comfortable environment for every guest helped Grossinger’s become the Rolls-Royce of the predominantly Jewish Borscht Belt, but Jennie also took special pride in catering to a highly diversified clientele of races, religions, and classes. “Quietly and without fanfare, Grossinger’s has become a social laboratory,” said Grossinger upon receiving an Interfaith Movement award. Racial integration was a part of life at Grossinger’s, decades before federal laws mandated it, and few guests thought anything of it.

What distinguished Jennie Grossinger was how she skillfully combined the old-world notion of a man’s home being his castle with a modern American commercial marketing sense. She hired an experienced publicist to get the Grossinger’s name before the public and knew to put herself forward as the face of her resort, and by doing so branded herself and her establishment. This made her a pioneer in the field. “There weren’t many businesses open to women in those days,” said historian Jonathan D. Sarna, “and the values and virtues that made you a good hostess and someone whom people wanted to entrust their summers to made you a very successful matron of the hotel.” Grossinger was a millionaire woman entrepreneur in an era when those three words were rarely if ever joined. Martha Stewart and Sheryl Sandberg, meet your spiritual godmother. And have a little something to eat.

Stephen M. Silverman is the author of The Catskills, to be published this month by Alfred A. Knopf, and 10 other books, including David Lean and Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and his Movies. He wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a national conversation hosted by the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.