Yayoi Kusama, High Priestess of Polka Dots

The avant-garde Japanese artist attains retrospective status—and embarks on a fashion collaboration with Louis Vuitton

![]()

Yayoi Kusama in her New York studio. Image credit: © Tom Haar, 1971

Artist Yayoi Kusama established the Church of Self-Obliteration and appointed herself the “High Priestess of Polka Dots” to officiate at a gay wedding between two men in 1968. For their nuptials, she also designed the couple’s wedding outfit: a two-person bridal gown. (And instead of a Bible, they used a New York City telephone book for the ceremony, she told Index magazine.)

Since the wedding dress wasn’t included in the Yayoi Kusama retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, we can only imagine what it might’ve looked like. Nonetheless, from the late ’60s-specific paintings, sculptures, collages, videos, posters and fliers included in the show—that closes this Sunday, September 30!—we can presume what the lucky couple would’ve been wearing.

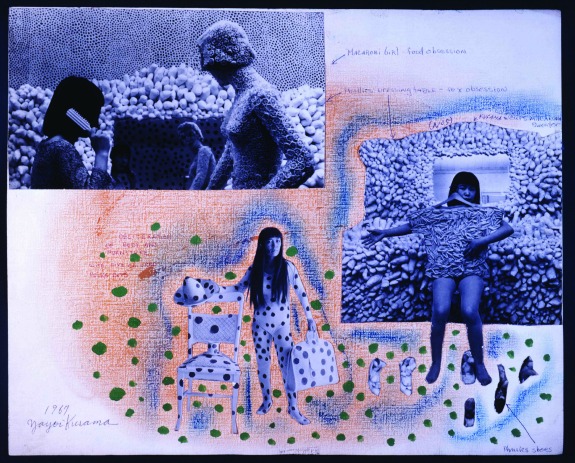

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration No. 3, 1967. Watercolor, ink, pastel and photocollage on paper, 15 7/8 by 19 13/16 inches. Collection of the artist. © Yayoi Kusama. Image courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo; Victoria Miro Gallery, London; and Gagosian Gallery, New York.

At 83 years old, Kusama is arguably the be-spotted queen of dots, known for obsessively painting them on everything throughout her prolific career— canvases, chairs, cats, clothing and bodies. This compulsion, along with a work-yourself-to-the-bone drive, propelled Kusama to leave New York City in 1973 after a 16-year stint and check herself into a psychiatric hospital in Japan, where she has lived and made art ever since (although not before greatly influencing the work of her contemporaries, including Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol and Donald Judd).

As a young, struggling Japanese artist in New York in the 1960s, she established the avant-garde fashion label Kusama Fashion Company Ltd., sold for a time at the “Kusama Corner” in Bloomingdale’s. Dresses were adorned with spots or, inversely, were full of holes (might this have been Rei Kawakubo’s early inspiration?), including those that were smack-dab on the wearer’s posterior. Her designs were see-through, silver, gold, or complete with phallic protrusions, another Kusama signature. As recounted to New York magazine by Kusama:

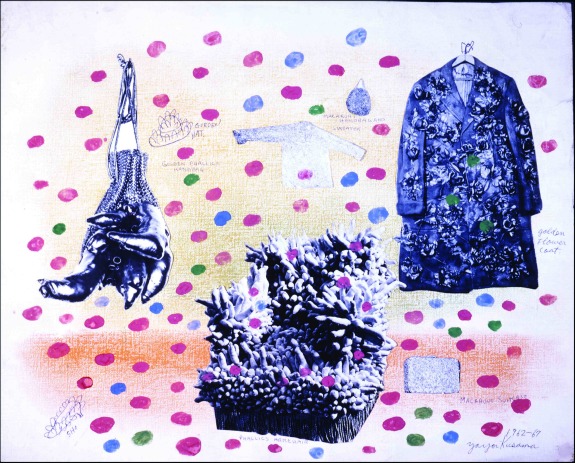

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration No. 1, 1962—7. Watercolor, ink, graphit, and photocollage on paper, 15 7/8 by 19 13/16 inches. Collection of the artist. © Yayoi Kusama. Image courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo; Victoria Miro Gallery, London; and Gagosian Gallery, New York

“An evening gown with holes cut out at the breast and derriere went for as much as $1,200,’”while her See-Through and Way-Out dresses were popular with “the Jackie O crowd.” She designed the “sleeping-bag-like Couples Dress” to “bring people together, not separate them,” while the Homo Dress, “with a cutout section placed strategically in the rear,” went for fifteen dollars.

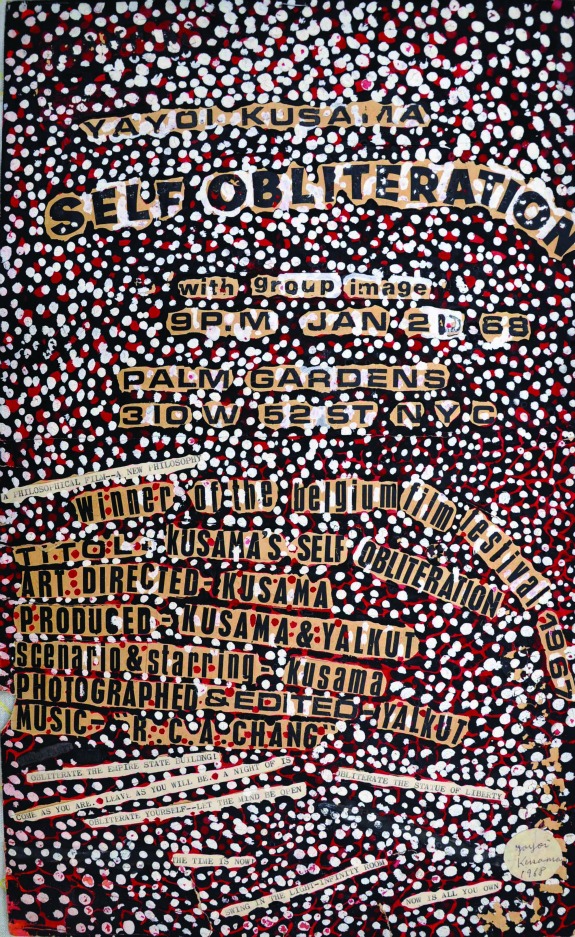

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration (original design for poster), 1968. Collage with gouache and ink on paper, 18 1/8 by 11 inches. Collection of the artist. © Yayoi Kusama. Image courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo; Victoria Miro Gallery, London; and Gagosian Gallery, New York

Just like the polka dots, soft protuberances were frequently incorporated in Kusama’s clothing, art, and everyday activities, like shopping at a supermarket wearing a dress and hat adorned with those hand-sewn phalluses. In a 1998 interview with Index magazine, Kusama addressed the proliferation of phallic symbols: “I liberated myself from the fear by creating these works. Their creation had the purpose of healing myself.”

Collection of the artist. © Yayoi Kusama. Image courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Kusama’s exploration of the human body went beyond an anxiety associated with male genitalia and sex. She staged happenings around New York City, and in performances she called Self-Obliterations, she painted spots onto naked bodies. As she explained to BOMB in 1999, referring to herself in the third-person, “Painting bodies with the patterns of Kusama’s hallucinations obliterated their individual selves and returned them to the infinite universe. This is magic.” And to Index she reasoned, “If there’s a cat, I obliterate it by putting polka dot stickers on it. I obliterate a horse by putting polka dot stickers on it. And I obliterated myself by putting the same polka dot stickers on myself.”

For more on Kusama’s relationship to clothing, fashion, and the human body, head over to her show at the Whitney before it closes this Sunday and make sure to spend some time with the primary sources and found materials in the show. And if Kusama’s work leaves you with an insatiable craving for polka dots, consider her spotty handbag collaboration with Louis Vuitton.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)