Record-Breaking Rocket Sled Created Modern Safety Standards

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Sonic_Wind.jpg.jpg)

On a clear December day in 1954, Colonel John Stapp, a physician and flight surgeon, strapped in for a ride that would earn him the nickname of “The Fastest Man on Earth.”

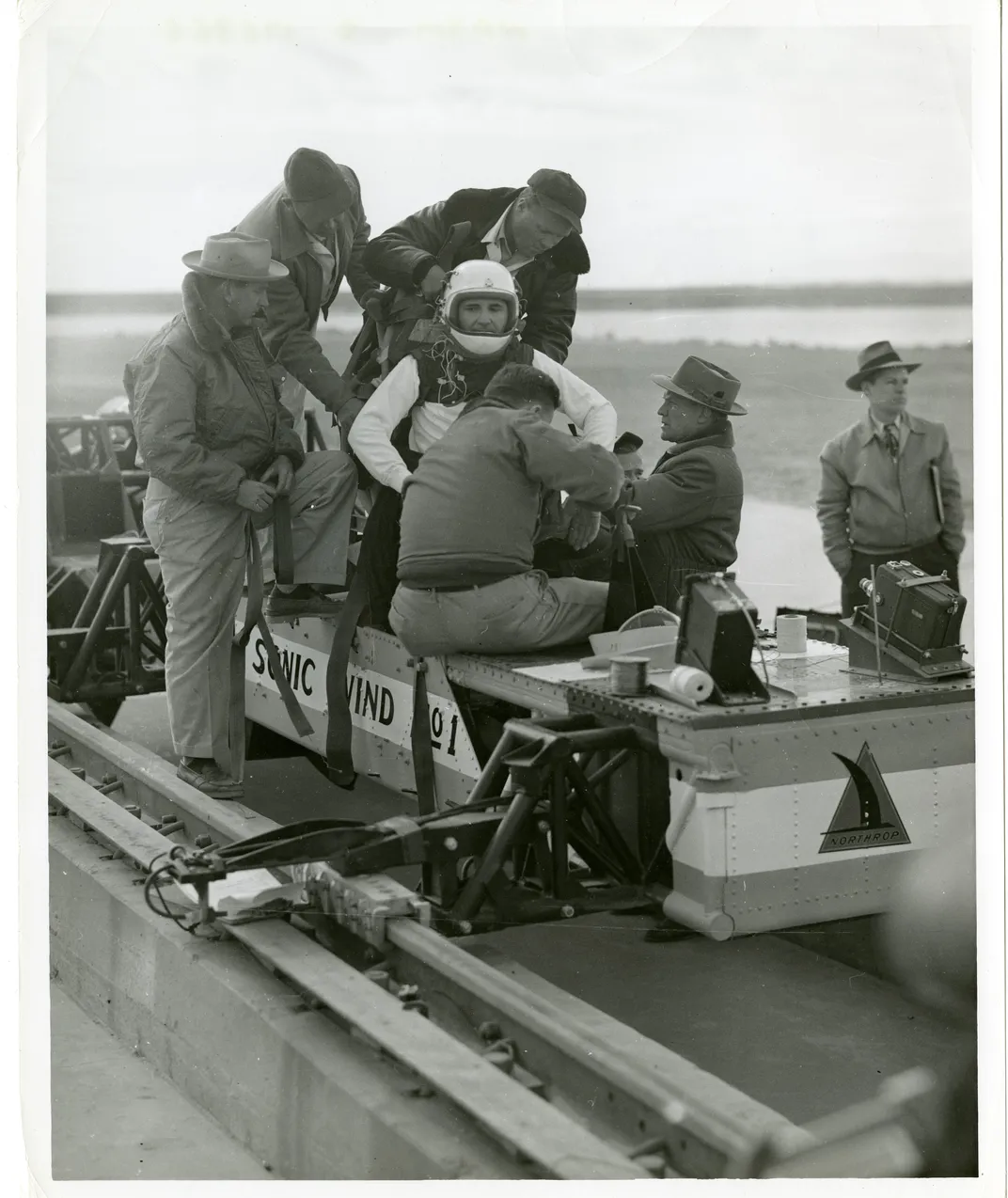

Stapp was testing what he called the Sonic Wind No. 1, a red-and-black painted rocket sled—a test platform that slides along a set of rails—powered by nine solid fuel rockets. Attached to the top of the sled was a replica jet pilot’s seat. The sled would propel forward on the track, which had a system of water dams at the end to stop it—all with Stapp in the pilot’s seat, strapped in and unable to move.

Why was Stapp ready to endure this risky test? He was studying the effects of high-speed acceleration and deceleration on the human body, trying to figure out how to keep pilots safe during airplane crashes. While conducting his research, Stapp became the test subject.

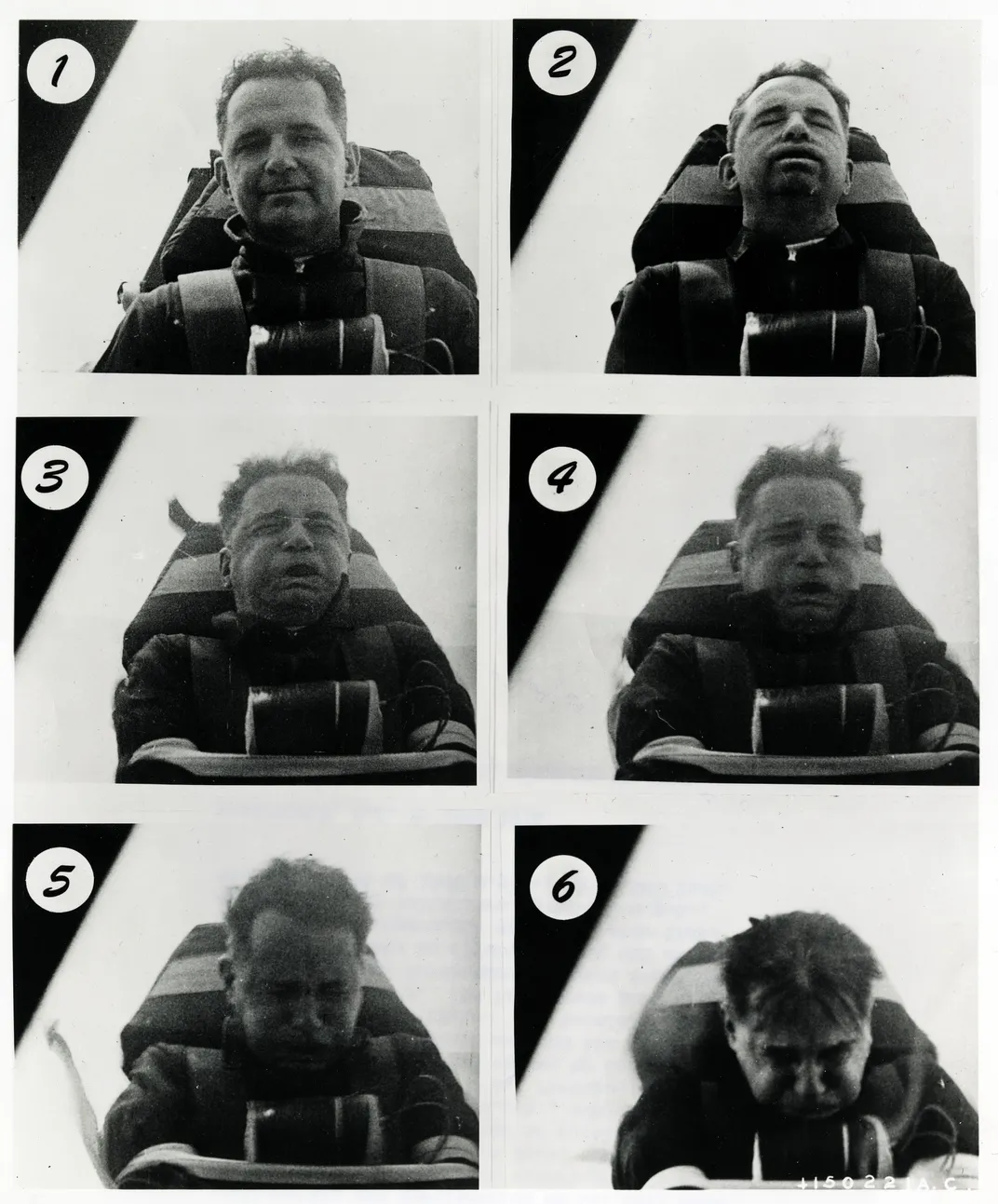

During his famous 1954 ride on the Sonic Wind No. 1, Stapp reached a speed of 1,017 kilometers per hour (632 miles per hour), faster than a .45-caliber bullet. It took the sled only 1.4 seconds to reach a full stop at the end of the track, but during that short time Stapp experienced a force of nearly four tons. It was a force that broke his ribs and wrists, and even temporarily blinded him. Though he was banged up, he survived the Sonic Wind No. 1 test with no permanent injuries, and earned himself a world land speed record in the process.

The data from Stapp’s research was used to create transportation safety standards that we still use today. Things like strengthening jet pilot’s seats to withstand stronger forces, and improving car seat belts are thanks to Stapp’s Sonic Wind testing.

Now, as part of the transformation of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, Stapp’s Sonic Wind No. 1 will be on public display. The story of the rocket sled will be part of the new Nation of Speed exhibition, which will explore human ingenuity and the pursuit of speed on land, sea, air, and space—a fitting place to feature the work of “The Fastest Man on Earth.”

For more stories, updates, and sneak peeks at what’s changing at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, check out airandspace.si.edu/reimagine, or follow along on social media with #NASMnext.