The Myth of the German “Wonder Weapons”

National Air and Space aeronautics curator Michael Neufeld examines the myth of the Nazi wonder weapons and the oft-repeated statement that if Germany had had the V-2 and other “wonder weapons” sooner, they may have won the war.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/NASM-NASM2014-02556.jpg)

Last fall, as I was standing next to the V-2, the German World War II ballistic missile on display in our Space Race gallery, I heard a man tell his companion how lucky we were that the Nazis had not had it sooner, or they might have won the war. It is one of the most beloved and entrenched stories, especially in the English-speaking world, about the V-2 and other advanced weapons the Third Reich deployed at the end of that war.

On the face of it, that assertion makes a lot of sense. The Germans introduced the world’s first operational rocket fighter, jet fighter, cruise missile, and ballistic missile, all between the spring and fall of 1944. If they had fielded the Messerschmitt Me 163 and Me 262 fighters sooner, could they have greatly impeded the daylight strategic bomber offensive?

U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) leadership certainly were concerned. If the Nazis had begun firing V-1 cruise missiles and V-2 rockets at Britain earlier, could they have disrupted the D-Day invasion preparations or caused mass panic, derailing the British war economy? Key Allied leaders like Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and Prime Minister Winston Churchill had discussed those very scenarios. From the Nazi side, Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels stoked fear with claims, beginning in 1943, of coming Wunderwaffen (wonder or miracle weapons) that would turn the tide and exact Vergeltung (vengeance or revenge) for the indiscriminate Allied bombing of German cities. After the war, the feeling in the West that we had experienced a close call was reinforced by the memoirs of German ex-generals, who blamed Hitler for holding these weapons up. As a result, the new fighters and missiles allegedly came “too late” to change the course of the war.

Fear of Germany’s advanced technology had been a constant since the 1930s. It led directly to the U.S.-British-Canadian atomic bomb project, after German physicists first detected nuclear fission in Berlin at the end of 1938. Hitler himself made vague threats of coming superweapons in 1939, perhaps thinking of the Army’s ultra-secret rocket project that would yield the V-2. When British intelligence detected that program in spring 1943, Churchill ordered a special air raid on the Peenemünde rocket center on the Baltic. Carried out in August, it was designed to kill the rocket engineers and disrupt the project, but was only a partial success. In late 1943 and early 1944, the construction of missile launch and storage sites in northern France led the Allies to divert strategic bombers to try to put the sites out of operation.

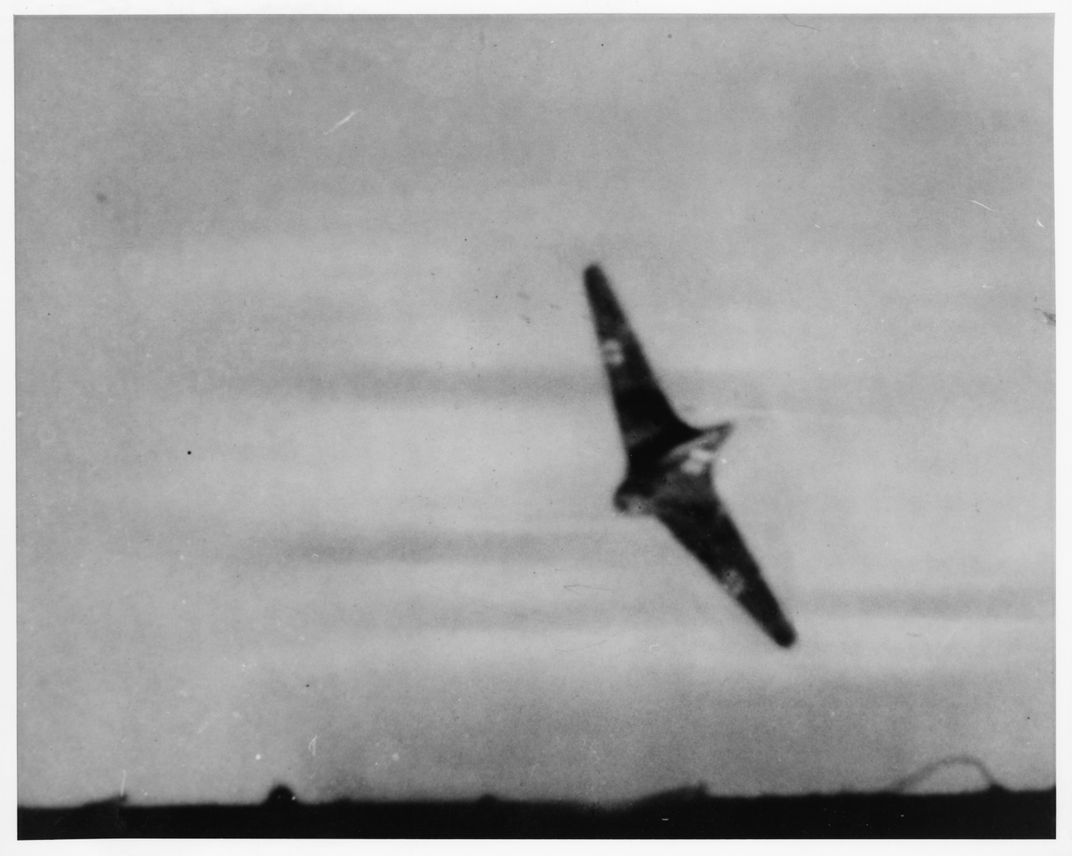

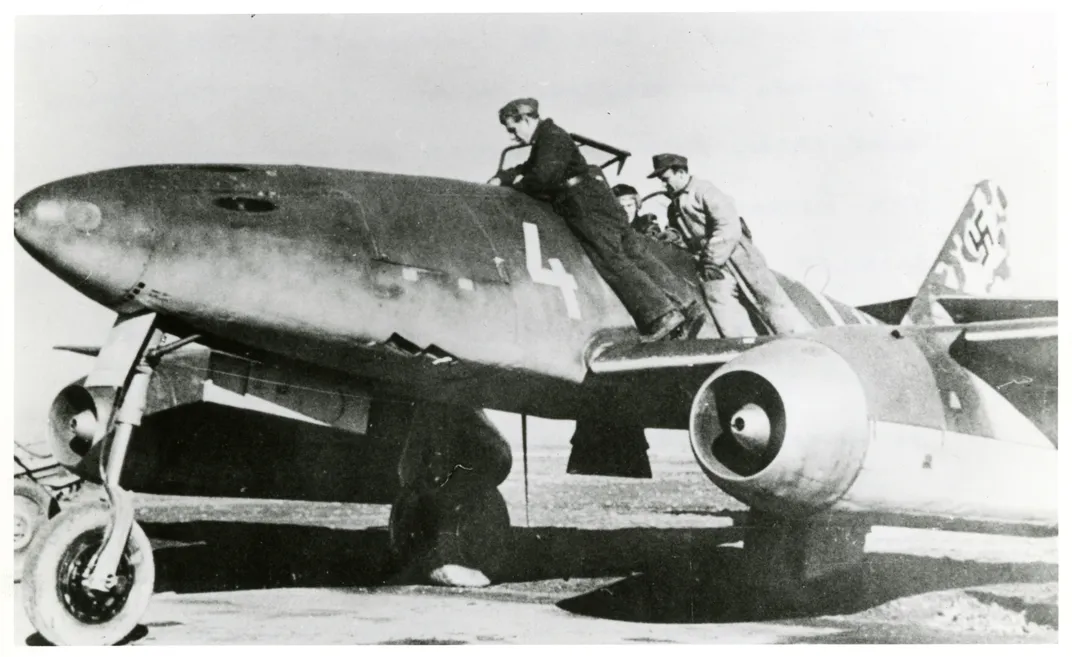

In spring 1944, USAAF concern peaked regarding the imminent appearance of German reaction-propelled fighters. The Me 163 rocket interceptor first entered combat in May, zooming through bomber formations at high speed. In late July, the first Me 262 turbojet aircraft were deployed as well. Yet there was no crisis. The Me 163 flew so fast that it was challenging to carry out a gunnery run on an American bomber and it exhausted its propellants in five minutes, at which point the pilot would glide back to base. U.S. fighter pilots soon learned to intercept them during the glide phase or lurk about the landing fields to shoot them down, which was feasible because of growing Allied air superiority.

The Me 262 was more effective because it had more conventional flying characteristics and a speed advantage over piston-engine opponents. But it was also vulnerable to being attacked on landing. In any case, the Me 262’s jet engines, being brand-new technology, had to be overhauled every few flight hours, or they would catastrophically fail.

Between the combat appearance of the two fighters, the Luftwaffe also began launching its Fieseler Fi 103 “flying bomb”—what we would now call a cruise missile. Days after its debut against London on June 13, Goebbels finally hit upon a propaganda name he liked: V-1 for Vergeltungswaffe Eins (Vengeance Weapon One). It made the biggest impression of any “wonder weapon.” Launched off steam catapults in northeastern France, dozens of V-1s soon began penetrating British airspace day and night, causing a mass exodus of children and families from London. Churchill was so concerned he tried to talk Allied leaders into dropping poison gas on German cities. Yet that crisis soon passed too. By August, the reorganization of British anti-aircraft defenses greatly increased the number of missiles shot down, and at the end of the month, Allied forces overran the Channel coast after the breakout from Normandy. Thereafter, only small numbers of V-1s were launched against southeast England from Heinkel He 111 bombers based in the Netherlands. Hitler ordered a shift in focus to the newly liberated Belgian port of Antwerp, which was needed by the Allies to supply its armies.

Army crews first successfully fired the V-2 against Paris and London on September 8, but Goebbels held off announcing it for two months, as the Ministry’s exaggerated V-1 propaganda had led to disillusionment inside the Reich. Arriving supersonically, the V-2 could not be shot down with 1944 technology, and its ton of high explosives, when combined with its impact velocity, created a massive crater. It was the most advanced and exotic weapon deployed in World War II—until the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Japan eleven months later.

Yet again the actual results of the V-2 were a lot less impressive than expected. Like its cruise missile predecessor, it was so inaccurate that it could only be aimed a large urban area and many failed during flight or exploded in the countryside. Manufacturing the V-2 cost at least ten times more than the V-1, and as result it was launched in much smaller numbers (about 3,000, as opposed to 22,000 V-1s). The very fact that there was no defense against the ballistic missile, other than futile attempts to try to find and bomb the mobile launch crews, meant that the Allies diverted fewer resources to stop it.

The Third Reich had earlier deployed the first air-launched, anti-shipping missile and the first precision-guided bomb in 1943, and it expended a lot of effort on developing anti-aircraft and air-to-air missiles for home defense, none of which it deployed. (The Henschel Hx 293, Fritz-X, Rheintochter R-1, the Ruhrstahl X-4 and other missiles are on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center.) The net result of all these weapons, deployed or otherwise, was that the Reich wasted a lot of money and technical expertise (and killed a lot of forced and slave laborers) in developing and producing exotic devices that yielded little or no tactical and strategic advantage. As for the one true superweapon of World War II, the atomic bomb, the Germans made only limited progress in nuclear technology. Arguments about the reasons for that failure have raged since 1945, but even if German physicists had created a nuclear reactor and a bomb design, it was very unlikely that the Reich could have built the huge isotope separation plants needed, given relentless Allied bombing.

Did the “wonder weapons” come “too late”? Quite the opposite: they came too early. Jet engine technology was still too new and temperamental, as were many of the component technologies of the new weapons. The V-1 and V-2 attacks, almost entirely on London and Antwerp, had no strategic result because the missiles lacked accurate guidance systems and nuclear warheads. Anglo-American conventional, four-engine aircraft were far more effective at strategic bombing. In any case, Hitler had lost the war in 1941 when he attacked the Soviet Union and declared war on the United States, with the result that Germany was arrayed against not just one great power (the British Commonwealth), but three. It took until late 1942 for the manpower and production imbalance to manifest itself on the battlefield, but thereafter the Third Reich was bludgeoned into submission by Allied superiority. So, when you next visit our location in Washington, DC, or the Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia, you may admire our world-class collection of advanced German aircraft and missiles, but please do not tell your companions that if they had only come sooner, the Nazis might have won the war.

Michael J. Neufeld is a senior curator in the Museum’s Space History Department and is responsible for German World War II rockets and missiles, among other collections. His books include The Rocket and the Reich (1995), Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War (2007), and Spaceflight: A Concise History (2018).