Launching Astronauts from American Soil: Why is it Important?

Curator Margaret Weitekamp reflects on the return of human spaceflight from US soil, and the implications of that capability throughout history.

:focal(2144x1424:2145x1425)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/572464main_fd11flag_full.jpg)

The upcoming launch of the Crew Dragon spacecraft from Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida ends the longest period ever between NASA’s human spaceflights launched from American soil. The time from the final space shuttle mission in 2011 until this flight is just about two months shy of nine years. The longest previous gap between U.S. human spaceflights was about three months short of six years (between the Apollo Soyuz Test Project [ASTP] in 1975 and the first flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1981). As a result, this launch represents an important milestone. The broader significance of launching American astronauts from U.S. soil, however, is rooted in the history of human spaceflight as a battlefield of the Cold War.

The Space Age—and the Space Race—began during the political, economic, social, and cultural conflict that existed from 1947 to 1991 between the United States and the Soviet Union. As nuclear-armed superpowers, neither side could afford to have a direct confrontation turn into a “hot” shooting war. So, the “cold” conflict was carried out through proxies, including spaceflights. From the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the use of missiles as launch vehicles demonstrated not only the ability to put an artificial satellite into orbit, but also the knowledge that such vehicles could direct nuclear weapons against an enemy. Launching a human being into space demonstrated a technological achievement that was an order of magnitude even more complex.

By carrying out these missions, both of the first two spacefaring nations aimed to impress the rest of the world, gathering adherents. Over time, other nations developed their own launch capabilities. By doing so, they joined what Israeli scholar Dr. Deganit Paikowsky (a former fellow at the Museum) has called “the space club.” As analyzed by Paikowsky, the theoretical space club has different levels of accomplishment—and associated prestige. Launching humans on one's own rockets is the ultimate level, one only attained by three countries (the U.S., USSR/Russia, and China). The use of space launches to exert soft power continues even though the Cold War is long over. In a somewhat loose analogy, having a national launch capacity can be compared to a metropolitan area having a major league sports franchise. It lends prestige, inspires excitement, and reinforces status.

The decision to reclaim a native human launch capacity makes sense for the United States even without the broader Cold War history that shaped the origins of spaceflight. After decades of sending astronauts into space, deciding to abandon a human launch capability would have been a major step. Writers and artists have long imagined that someday, humanity would be a spacefaring species. Although scientists have discovered just how much of our solar system and universe can be explored without a direct human presence, the photographs that astronauts and cosmonauts take still have a special resonance because we can imagine ourselves in their place.

Notably, unlike the previous gap between the ASTP and shuttle missions, U.S. efforts in human spaceflight never stopped during the last nine years. American support of the International Space Station (ISS) continued through crew exchanges carried out via Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Indeed, this fall will mark the 20th anniversary of the launch that began two decades of continuous human occupation on the station. Americans have actively been a part of the small community living and working in low Earth orbit. Having both the Crew Dragon and Cargo Dragon in operation will strengthen the supply lines supporting the space station.

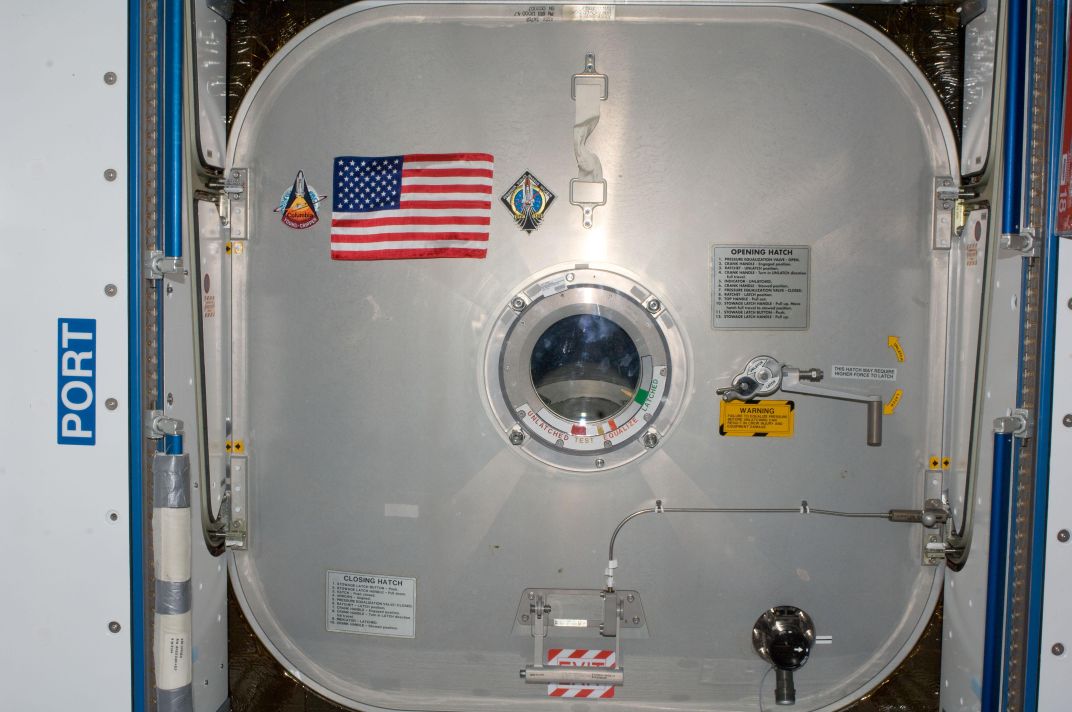

When the Crew Dragon mission docks with the ISS, NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken will retrieve an American flag that has been waiting there for this moment. Flown aboard STS-1 and again on the final space shuttle mission STS-135, the deeply symbolic talisman links this mission to earlier launches in the long history of American human spaceflight.

Margaret A. Weitekamp is the department chair of the Museum’s Department of Space History. As a curator, she is responsible for the Social and Cultural History of Spaceflight collection.