Space Shuttle Astronauts Tell All

A new book by NASA astronaut Tom Jones shares intriguing stories about the agency’s longest-running space exploration program

:focal(500x376:501x377)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/6c/3a6cd655-6717-44b8-af03-27a20181b5d8/shuttle_s81-39563_edit.jpg)

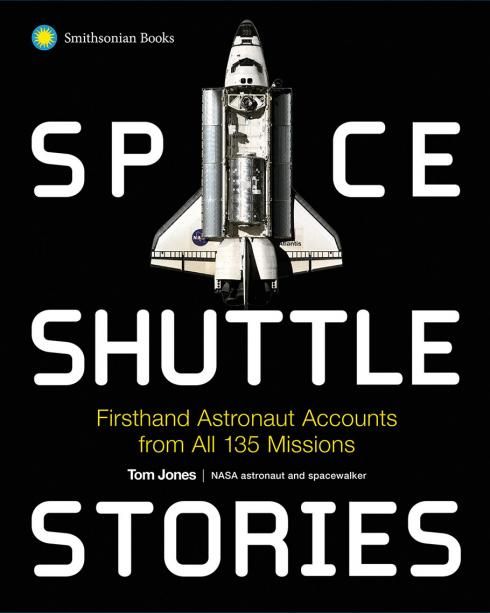

Planetary scientist and pilot Tom Jones had a long career as an astronaut. While at NASA, he completed four space shuttle missions and three spacewalks to help build the International Space Station. In his latest book, Space Shuttle Stories, Jones documents the shuttle program’s 30-year history by interviewing more than 130 fellow astronauts. They discuss their broad range of experiences—beginning with Columbia’s first flight (in 1981) and ending with the program’s final mission, flown by Atlantis in 2011. Featuring more than 500 photos from NASA’s archives, Space Shuttle Stories focuses on the human aspect of the missions. Jones was recently interviewed by Air & Space Quarterly senior editor Diane Tedeschi.

What did the space shuttle program get right?

The space shuttle was the most important program in NASA’s history. The shuttle was not only a groundbreaking spacecraft—a reusable, winged spaceplane—but it gave the United States a versatile work and science platform with which to master operations in low Earth orbit. The shuttle was so far ahead of its time that no other nation has flown anything even approaching its capabilities. Despite its fragility and operational expense, the shuttle became the iconic symbol of America’s presence in space. What we know how to do well in space today, we learned on the shuttle. We’ve successfully applied those skills to the International Space Station, soon to be practiced again on the moon.

After the loss of Challenger and Columbia, did active-duty astronauts feel free to express their concerns to NASA management?

Astronauts are not reticent in expressing their opinions. Chief astronaut John Young raised an alarm well before Challenger when he wrote a memo to Johnson Space Center management. He pointed out how the shuttle’s accelerating schedule threatened NASA’s safety practices: “If we do not consider Flight Safety first all the time at all levels of NASA, this machinery and this program will NOT make it.” Despite such warnings, shuttle managers pressed ahead, trying to resolve shuttle flaws while simultaneously increasing the pace of the launch schedule. Before Challenger’s tragic mission (STS-51L), astronauts were unaware of the ongoing, worrisome problems with the flawed solid-rocket booster joints, and STS-51L’s crew was never informed of the debate over how cold temperatures at the launchpad could further degrade the joint’s performance. On launch day, the astronaut office’s leadership was not asked if they judged the shuttle’s boosters safe to launch—nor did they know of the danger. The avoidable accident shocked every astronaut, even experienced combat fliers.

What was the most interesting thing an astronaut observed during a shuttle flight?

Each astronaut has their favorite, but I will go with my own experience on STS-68, Space Radar Lab 2, when we launched into a high-inclination orbit that took us from the latitude of the Aleutians down to Tierra del Fuego on each revolution. On Flight Day 1, we soared over east Asia at 138 miles up and spotted a huge cloud silhouetted on the distant horizon. Our crew wondered whether it was a thunderstorm’s anvil cloud or perhaps a dust cloud raised from the Gobi Desert. As Endeavour carried us over Kamchatka, we looked straight down the throat of the Kliuchevskoi volcano in full eruption. The volcanic peak had serendipitously blown its top on our STS‑68 launch day, September 30, 1994. All six of us were plastered to the windows like bus tourists at a Grand Canyon overlook.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b5/b3/b5b3d383-9735-4cac-b507-282a0f93cf35/sts068-214-035orig.jpg)

What is the funniest story you heard?

One favorite from the interviews (I wish I’d had space to include it in the book) was Anna Fisher’s tale from STS-51A, when she and commander Rick Hauck were alone on the flight deck, about to execute the final, critical rendezvous burn to rescue a crippled satellite. The rocket burn was just minutes away when Rick told Anna it was absolutely imperative he duck down to the middeck to use the bathroom. “Rick! We’re coming up on the [rocket] burn! We need two sets of eyes on all these checklist inputs.” Hauck, heading below, shot back: “Just check it twice!”

What is the most chilling story that appears in the book?

That would have to be STS-27 in 1988. After Atlantis’ liftoff, debris shed from the right booster’s nose cap struck the orbiter and damaged hundreds of heat-shield tiles. In orbit, mission control advised the crew to use the robot arm’s TV camera to examine the shuttle’s right side and wing. Commander Hoot Gibson reacted to that first view: “We looked at that right wing and I said to myself, ‘We are going to die.’ I was looking at more than 700 shredded tiles.”

Houston told the crew the tile damage wasn’t a serious concern, perhaps because the encrypted TV transmissions from this classified national defense mission degraded the downlinked images. Through gritted teeth, Gibson flew Atlantis into the peak heating phase of reentry, monitoring gauges for any signs the right wing had been compromised. After landing, the crew saw that an entire tile had burned away on the lower right nose, partially melting the exposed metal beneath. Only the extra thickness of a steel antenna door at the site prevented a burn-through. In 2003, Columbia’s damaged left wing had no such extra protection.

What does a shuttle reentry feel like?

To my mind, the shuttle’s hypersonic reentry surpassed the physical and visual thrills of ascent. First, it lasted close to an hour versus the eight and a half minutes of ascent, carrying the descending orbiter from west of Australia to Florida. Second, reentry was far more visually exciting than launch, with the shock-generated, incandescent plasma wrapping the cabin windows in an intense, orange-pink glow. During peak heating from about Mach 22 down to Mach 15, a white-hot plume streamed behind the orbiter, recombining in a staccato series of flashes like a crowd of paparazzi mobbing a film premiere’s red carpet. Rivers of 3,000-degree ionized plasma washed over the front windows, yet our cabin interior remained at about 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

Third, and perhaps most impressive, was watching the shuttle fly itself on autopilot halfway round the world to arrive precisely above the Kennedy or Edwards runway, ready to hand over control for landing to its skilled commander. That unforgettable hypersonic passage was never less than a technological tour de force.

This article is from the Fall issue of Air & Space Quarterly, the National Air and Space Museum's signature magazine that explores topics in aviation and space, from the earliest moments of flight to today. Explore the full issue.

Want to receive ad-free hard-copies of Air & Space Quarterly? Join the Museum's National Air and Space Society to subscribe.