AMERICAN WOMEN'S HISTORY INITIATIVE

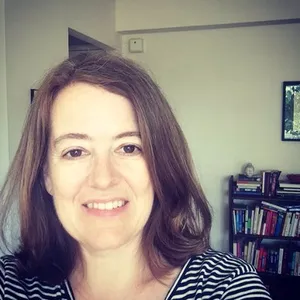

A Conversation with Effie Kapsalis

Effie Kapsalis has a cool job. As the Senior Digital Program Officer for the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, she works with curators and researchers to uncover girls’ and women’s stories embedded deep within the Smithsonian and give them a new life—and long-deserved recognition—online. Recently, we talked with her about the Smithsonian’s “digital-first” approach to women’s history, correcting the Wikipedia gender imbalance and finding inspiration from an early 20th century museum elevator operator who became an expert on insects.

:focal(278x410:279x411)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/bw_EffieKapsalis.jpg)

Effie Kapsalis has a cool job. As the Senior Digital Program Officer for the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative, she works with curators and researchers to uncover girls' and women's stories embedded deep within the Smithsonian and give them a new life—and long-deserved recognition—online.

Recently, we talked with her about the Smithsonian's "digital-first" approach to women's history, correcting the Wikipedia gender imbalance and finding inspiration from an early 20th century museum elevator operator who became an expert on insects.

Q: The Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative is a "digital-first" initiative. Why is it important to lead with a digital approach?

The Smithsonian has captured a lot of content related to women and girls through our 172 years of collecting and studying, though much of this content—especially from the early years—is often below the surface. What we considered important to capture and study in the 1800s was vastly different than what we'd focus on today. In 2019, the Smithsonian can take advantage of tools in machine learning to identify gaps in information and improve it at-scale. We also have more sophisticated means to reach people with these stories of women and girls who were below the surface. For the American Women's History Initiative, it's important that we take not only a "digital-first" approach but an "audience-first" approach. For American women, this is OUR history. We have deeply personal connections and feelings about it. Before the Smithsonian embarks on big digital things, we need to pause to better understand who we are serving and the ways in which they want to connect.

Q: Can you give a couple of examples of Smithsonian digital projects that have illuminated women's stories in surprising ways?

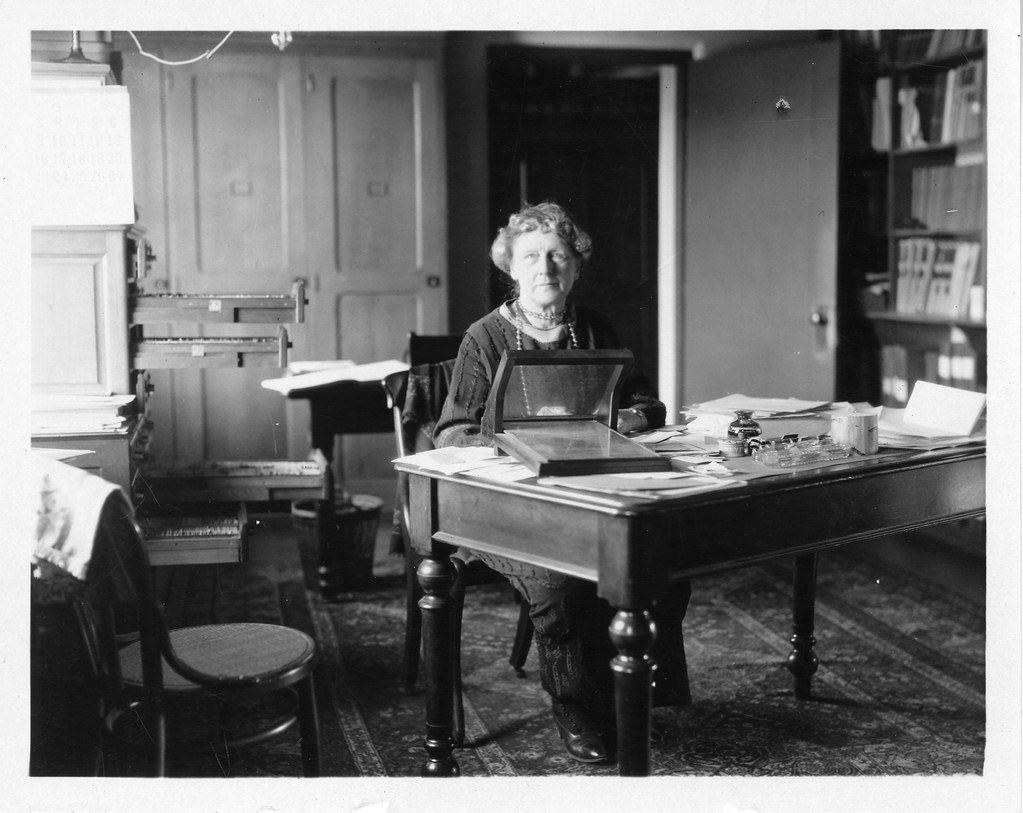

At the Smithsonian Institution Archives, we developed a model that employed human expertise, crowdsourcing and open source digital platforms to uncover women's stories. This is critical to address the gender imbalance we see online. A glaring example: Only 18% of biographies on Wikipedia—one of the top 10 websites worldwide—are of women. Our amazing Archives research fellow and historian, Dr. Marcel C. LaFollette, identified hundreds of "hidden figures" in a 1920s-1970s science news collection. Over time, through Flickr Commons and the Archives' blog, the public responded to our calls to supply information on the unknown figures. Our digital records grew richer, and we garnered some serious archives-lovers along the way. Through partnerships with Wikimedia DC, we invited the public to build on this work. We published 75 new Wikipedia articles about women in science, and improved hundreds of others. These women all of a sudden had a digital legacy. With the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative, we are turbo-charging this process with new tools and resources. A digital curator dedicated to the history of women in science will join our Archives in the next few months to flesh out hundreds more biographies. Our Research Computing Lab will soon bring on a data science research fellow to determine how we can better represent women in science across all Smithsonian digital resources. We plan to diversify crowdsourcing tasks, to not only improve what we have but share it as widely as possible.

Q: How will you use digital platforms to spark conversations about women's roles and gender equality in the United States today?

There will be tons of rich conversations, both in person and online, during the development of projects, as well as those facilitated by the digital projects we launch.

Right now, we are working directly with our primary audiences (middle-school students, college students and women and girls of color) to understand their views and desire to engage on the topic.

Just this week, I participated in a workshop organized by the Georgetown Ethics Lab and the Hirshhorn Museum ARTLAB+ on the topic of girls' history, in preparation for a June 2020 exhibition, Girlhood: It's Complicated, at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

We had deep conversations about what metropolitan Washington, D.C., teens want to communicate about girlhood. Teens then participated in a "rapid design" exercise to develop a mobile interactive that will extend the Girlhood exhibition experience across the National Mall and online.

Additionally, a project organized by the Smithsonian Learning Lab and the National Museum of Natural History, in conjunction with undergraduate students at American University, will look at how we can make our online women's history collections and scholarship more accessible.

And a five-year curators' symposia series will address issues of women at work, starting internally with the history of women workers at the Smithsonian and in federal government, and then branching out to women in various sectors. We still have a lot to say on this topic, about how women from a variety of cultural and gender-identity backgrounds are treated in the official workplace, at home and in communities. We will bring in participants via chat rooms and webcasts to engage on this important topic.

Q: Of all the women's stories you've uncovered in your work, is there one that left you particularly inspired?

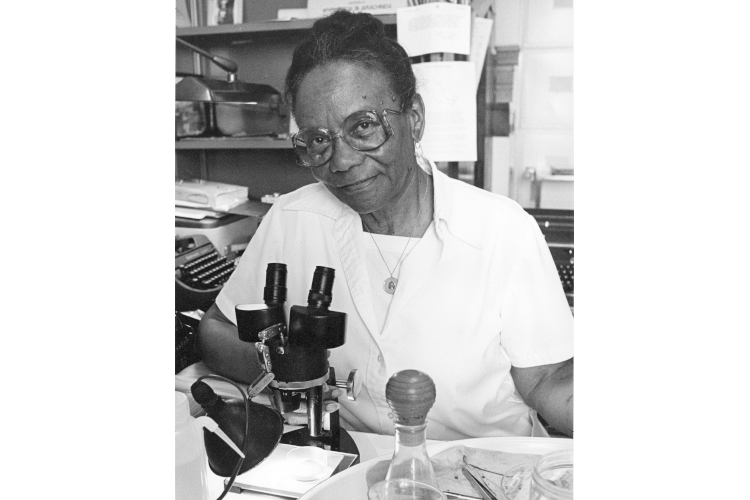

Hands-down, it's the story of Sophie Lutterlough, a research assistant at the National Museum of Natural History. As an African American woman born in 1910, Lutterlough did not have access to traditional scientific training. However, what she accomplished in a non-traditional path was amazing and paved the way for others.

In 1943, Lutterlough was hired as the museum's first woman elevator operator—she was told that she was the "test case" for women in that role. While in the elevator, and because of an interest in biology developed at Dunbar High School in Washington D.C., she sought to learn whatever she could to help visitors. In time, she became a mobile "one-woman information bureau" for the museum and eventually talked her way into a job as an insect preparator.

Knowing little about entomology, she consulted textbooks and coworkers, and took college courses in science, writing and German to gain the skills needed for the job. Within two years, she became a research assistant. She took on monumental tasks like restoring a collection of 35,000 dried-out ticks, which enabled her and her manager, Dr. Crabill, to discover some 40 "type specimens," which were then added to the museum's general insect collection.

These are the stories we want to capture with the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative: diverse stories of women, and individuals who identify as women, who paved the way for others despite all odds.

Sign Up to Join the American Women's History Community

You'll get the latest news, updates and more delivered directly to your inbox.

The Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative is supported in part thanks to people like you. Make a gift now and help us amplify women's voices, reach the next generation, and empower women everywhere.